Introduction and summary

The way workers are paid is changing, as electronic forms of payment are increasingly replacing cash and checks. For a large swath of moderately to highly paid workers who have access to bank accounts, the technological transformation from paper checks to direct deposit has mostly brought benefits. But for low-paid workers, who tend to have less access to the mainstream financial system, the transition to electronic payments is more complicated.

Payroll cards—an electronic form of workplace compensation that is a type of prepaid debit card—can provide unbanked individuals with increased access to the financial system, as well as the benefits of safety, convenience, faster payments, and ease of use that come with it. However, the emergence of payroll cards and similar products that may be developed in the future carries risks as well. Fees associated with these products may extract wealth from the very workers who can afford it least.

Unfortunately, consumer protections relating to how workers are paid have not fully caught up to changing payment practices. While elements of federal workplace and coFnsumer protection laws apply to payroll cards, there are glaring gaps that leave workers exposed to junk fees, such as those incurred by some workers for merely checking their account balances at ATMs. Only a handful of states—most notably, Connecticut,1 Hawaii,2 Illinois,3 New York,4 and Pennsylvania5—go significantly above federal requirements by banning certain kinds of junk fees; ensuring workers can access their funds several times each pay period without charge; and providing other protections. Still, most states, as well as the federal government, have a long way to go to meaningfully protect consumers from existing electronic payroll practices. Moreover, unless they change quickly, states are likely to fall even further behind as payment practices continue to evolve.

This report explains how workers are currently paid, highlights data showing an increasing use of payroll cards, describes the types of workers most likely to use payroll cards, and outlines the benefits and risks of this payment option. In addition, it reviews how the federal Fair Labor Standards Act and Electronic Fund Transfer Act provide workers with only limited protections and highlights the growing body of state regulations that have emerged to prevent the worst abuses. Finally, the report offers policy recommendations for federal, state, and local policymakers to make sure that workers are adequately protected and are not separated from their wages.

Notably, the policies recommended in this report include:

- Collecting better data about how workers get paid, the level of payment choice they receive at work, and the fees they may incur

- Improving protections for consumers by banning junk fees, prohibiting overdraft and other credit features, requiring deposit insurance, and ensuring better access to worker funds

- Requiring federal, state, and local governments to use best practices for payroll cards when paying their own workers and contractors

- Improving enforcement of payroll card laws to ensure workers receive the protections they are afforded by law

Several of the report’s recommended policy changes can be accomplished through executive action at the state and federal level, though some reforms will require legislation. While the policy recommendations in this report focus on payroll cards specifically, the principles underlying those recommendations are universal for any form of electronic payment.

The advent of payroll cards is the most recent innovation in how workers are paid, but it will not be the final one. As new technology and payment methods continue to evolve, policymakers must remain vigilant to any developments that threaten to separate workers from their wages. Workers should have a choice in how they are paid, and their hard-earned wages should not be eroded by a dizzying array of fees—no matter the form of payment.

Scope, opportunity, and risks of payroll cards

How workers are paid

The method by which workers are paid has undergone a substantial evolution. Employees are increasingly paid through electronic means—namely, direct deposit to a bank account or through a payroll card program—instead of by cash or check. According to the National Automated Clearing House Association (NACHA), in 1986, 8 percent of workers were paid through direct deposit.6 In 2000, that number jumped to more than 50 percent; and by 2015, it stood at 82 percent.7 This trend has mirrored the broader movement toward electronic payments across the U.S. economy. As recently as 2000, check payments for goods and services outnumbered electronic transactions in terms of noncash payments.8 By 2015, however, card payments and other electronic payments drastically outnumbered check transactions—by a factor of six.9 This trend toward electronic payments will only continue to increase.

While a sizable majority of employees have their wages deposited into their checking or savings accounts, a growing number of workers are receiving wages on payroll cards. Payroll cards are a type of prepaid debit card that in many ways function like a bank account. Every pay period, the employer deposits the employee’s wages—either full or, in some cases, a specified portion—directly onto the card. The employee can then use the card for point-of-sale transactions in stores; cash withdrawals and balance inquiries at ATMs or banks; and online bill pay, just as a consumer would use any other general purpose prepaid card or bank account. The employee’s funds are held in an account at an issuing financial institution, in which they usually, but not always, receive the benefit of deposit insurance from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) or the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA). Payroll card programs vary from employer to employer, with differing fee structures and additional services attached to the card.

Estimates suggest that the prevalence of payroll cards has grown substantially in the past decade and is likely to continue growing at a rapid rate as employers move away from cash and checks. In 2010, according to an industry estimate from payments consulting firm Aite Group, there were 3.1 million active payroll cards across the country, with $20.9 billion loaded onto those active cards.10 In 2017, both numbers doubled: There were an estimated 5.9 million active cards with $42 billion in load value.11 By 2022, those figures are expected to jump to 8.4 million and $60 billion, respectively.12 These figures far surpass the estimated 2.2 million workers who will be paid using paper checks in 2019.13

A 2014 Deloitte survey on payroll payment methods also found a meaningful increase in payroll card usage.14 From 2011 through 2014, payroll card usage jumped from 1 percent of U.S. workers to 5 percent, representing an increase from about 1.3 million workers to 7 million workers.15

It is also important to consider the breakdown of types of workers being paid with these cards. A 2018 study from the Center for Financial Services Innovation (CFSI) found that relative to the population of working Americans, payroll card users tend to be younger, occupy lower-income brackets, and have higher representation from certain communities of color.16 The demographic, income, and age trends of payroll card users generally line up with the latest data collected by the FDIC on the broader universe of prepaid card users.17 Publicly available information also points to the retail, manufacturing, and fast-food industries as key sectors that use payroll cards.18 Given the profile of workers paid using these products, it is not surprising that the cards are prevalent in these industries.

Still, it is important to note that there is a lack of robust public data on payroll card usage and user demographics. While the industry and nonprofit studies and surveys cited above are reasonably designed and executed, the results are not always consistent. Furthermore, there are no holistic government-produced reports specifically focused on this market.19 The need to close the data gap on these products is discussed in the policy recommendations section of this report.

Payroll card advantages

The growth of payroll card adoption presents clear advantages and risks for both workers with and without bank accounts. The benefits of this payment method differ depending on the level to which the user is already integrated into the traditional financial system. Payroll cards can serve as an important way for workers who are unbanked—those who do not hold basic financial products such as savings and checking accounts—to experience the benefits that come with access to the mainstream financial system. For employers, electronic forms of payment, such as payroll cards, are significantly cheaper to administer than payment by check. And for governments, it is easier to investigate wage theft allegations when private employers use payroll cards than when workers are paid through cash payments.

For unbanked workers, a payroll card may be a much better payment option than cash or checks. Payment in cash can be inconvenient and is more likely to be lost or stolen, compared with an electronic fund transfer onto a payroll card. Payroll cards have procedures to resolve errors and limit customer liability in cases of fraudulent charges and lost or stolen cards. Moreover, with a payroll card, workers do not need to physically pick up their wages from an employer or wait for the mail to arrive if paid by check. Natural disasters, personal or family illnesses, lost checks, or other obligations may disrupt and delay an employee’s ability to receive wages in person or by mail. With payroll cards, funds are directly deposited onto the card on payday, and the employee typically has access to those funds immediately. Payroll card users are able to withdraw cash—either from ATMs or financial institutions—and can use their cards for point-of-sale transactions or for online bill pay. This functionality provides unbanked employees with many of the same benefits that individuals with bank accounts and debit cards enjoy.

In addition to the benefits of safety and convenience, payroll cards can be a significantly cheaper alternative to payment via check for unbanked employees—although there can be risks, which are discussed below. Check-cashing fees for the unbanked can be excessive, draining worker wages. These fees can be as high as 1 to 5 percent of an unbanked worker’s paycheck, depending on the state and the pricing offered by local check-cashing institutions.20 Even assuming moderate fees, an unbanked worker making $20,000 annually could pay $400 or more a year in check-cashing fees.21 It is nearly impossible for employees to avoid these fees when they are paid by check and do not have access to an affordable bank account. This type of fee makes the already precarious financial position of low-income workers that much worse. Individuals cannot afford to and should not have to have their wages eroded when they try to simply access those hard-earned dollars. The $400 a year in check-cashing fees comes into focus when considering that, currently, 40 percent of Americans do not have enough savings to cover a $400 emergency expense.22 Check-cashing fees extract wealth from workers who can afford it the least and simply make it more difficult for them to build personal financial stability.

Unbanked Americans

While outlining the benefits that payroll cards present, it is particularly helpful to identify the subset of Americans who fall into the category of “unbanked.” According to the FDIC’s 2017 National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, an estimated 6.5 percent of households—roughly 14.1 million adults—were unbanked in 2017, meaning they did not have a checking or savings account.23 The rate of unbanked U.S. households is nearly four times higher for those with annual family incomes below $15,000 and almost double for those with incomes between $15,000 and $30,000.24 Relative to white households, black and Hispanic households were approximately five times as likely to be unbanked.25 Unbanked individuals also tend to be younger.26

On a positive note, the economic recovery has helped decrease the number of unbanked households to its lowest point since 2009.27 As the economy has recovered and employment levels have improved, more workers have had funds to put into a bank account. Moreover, a direct deposit from an employer is typically one of the transactions that triggers a free checking or savings account. According the 2017 survey, the dominant reason cited for households being unbanked—at 52.7 percent—was that they “Do not have enough money to keep in account,” followed by “Don’t trust banks,” 30.2 percent; “Avoiding bank gives more privacy,” 28.2 percent; and “Account fees too high,” 24.7 percent.28

The benefits of payroll cards can extend beyond just the unbanked. Two different surveys suggest that the sizable majority of payroll card users do in fact have checking accounts.29 Direct deposit to a bank account is probably an option for many of these workers, so it is likely that they see benefits in using a payroll card as a complementary financial product. For example, workers—and their families—in this category can use the payroll card as a budgeting tool. Instead of spending money directly out of a checking account, they can preserve funds in their bank account while spending only their wages, or some portion of their wages, in between pay periods. Workers using this strategy, however, are potentially exposed to the myriad fees charged by payroll cards, when they could avoid many of the possible fees by receiving their full wages through direct deposit to their checking account.

There is one area where a payroll card might be cheaper than a checking account. Many payroll card programs do not offer overdraft services. Overdraft services let a user register a negative balance, with the financial institution covering the payment instead of declining a transaction. These fees, which will be discussed in the next section, can be costly, and overdraft is frequently offered through traditional bank accounts. Using a payroll card that does not offer this service can shield workers from high overdraft fees if their alternative is a debit card linked to a checking account with overdraft activated. That said, some payroll card programs do offer overdraft services with high fees, and since 2010, overdraft has not been automatic; workers have the choice to opt into accepting overdraft services and fees in their checking account.

Overdraft services

Overdraft, originally extended as a customer courtesy, has become an expensive consequence of limited or irregular cash flow and expenses. Banks and credit unions advertise overdraft protection as a benefit, charging a fee to cover transactions that would otherwise be declined because the customer’s account lacks sufficient funds. This fee—typically around $34 per transaction—adds up quickly, especially as debit card transactions are approved over and over when there is no money in the account.30 In 2016, consumers paid a total of roughly $15 billion in overdraft fees.31 The vast majority of these fees are concentrated in a small number of customers in volatile financial situations. In a study of bank accounts at several large banks in the early 2010s, nearly three-quarters of all overdraft fees were paid by just 8 percent of accounts—those incurring more than 10 overdrafts—while 70 percent of accounts incurred no overdrafts at all.32 Most customers who use overdraft pay more than a single fee. Among these large bank customers, those who incurred at least one overdraft or non-sufficient funds fee paid an average of $225 in such fees over the course of a year.33 The resulting fees and penalties can drive individuals out of the banking system entirely if their accounts are closed due to excessive fees. Most prepaid cards have remained true to their name and have not contained overdraft options, but some cards do offer them.

Simply having a bank account does not necessarily mean that a consumer is fully served by the traditional financial system, and therefore, products such as payroll cards can prove useful. Additionally, higher-quality payroll cards may have better mobile functionality or budgeting tools than an employee’s bank account.

That said, the public should be skeptical of the implications of evidence suggesting that a large percentage of payroll card users do have bank accounts. Though it is likely that the functionality, budgeting, and overdraft explanations are indeed reasons for some people with bank accounts to opt for a payroll card over direct deposit, it is also possible that more nefarious reasons are at least partially to blame. Employers might be pushing employees into these products or making it more difficult to opt for direct deposit to an account of their choosing, despite the legal requirements that there be some level of employee choice regarding the method by which they are paid.34 Employees may not feel like they can exercise their right to select alternative payment options.

Payroll card risks

While payroll cards can provide benefits for the unbanked and even those with bank accounts, these products carry meaningful risks associated with their fee structures that can separate workers from their full wages. Nationwide data on the amount of payroll card fees accrued by workers annually is not publicly available—a clear consumer protection data gap that can and should be addressed. Setting aside the lack of national data, several studies and employee lawsuits paint a picture of the potentially severe pitfalls of at least some of the existing payroll cards in use.

Payroll cards can charge a variety of different fees. Workers could be charged for applying for or participating in the payroll card program; for checking their account balance at ATMs; for using customer service features; for maintaining their account; for having a low balance or account inactivity; for making point-of-sale transactions in stores or online; for being issued initial or replacement cards; for overdrafting their account; and for simply closing their account and requesting refund of remaining account funds. The breadth and cost of fees charged by payroll cards varies by payroll card program, but generally, free-checking accounts at a bank or credit union impose fewer so-called junk fees. Workers may also face payroll card fees for additional cash withdrawals beyond the one free withdrawal required by law. Some payroll card programs offer overdraft services or other credit features that enable workers to borrow funds through the card. These services may come with excessive fees and could saddle workers with debt. In some payroll card contracts between employers and financial institutions, employers receive financial incentives or kickbacks in exchange for offering a specific payroll card program that might be riddled with fees.35

For example, in 2013, Natalie Gunshannon, who worked at a Pennsylvania McDonald’s franchise, sued her employer for forcing employees to receive their wages on a payroll card with very high fees. Gunshannon already had an existing credit union account.36

The payroll card had sizable fees for making ATM withdrawals, for paying bills online, for withdrawing cash at a bank, for replacing lost or stolen cards, and even for simply checking the card balance at an ATM.37 Gunshannon argued that these fees quickly added up and took a significant bite out of her and her fellow colleagues’ wages. After favorable judicial rulings for the plaintiffs, the McDonald’s franchise settled the suit for almost $1 million and now offers alternative payment options.38

An investigation into fast-food chain Hardees provides another illustrative case. In 2014, a U.S. Department of Labor investigation found that the Hardees payroll card program cost workers an average of $2.10 a week, or about $110 a year.39 The fees pushed some workers’ pay below minimum wage, a violation of federal law.

In 2016, the Restaurant Opportunities Center United, a nonprofit organization that advocates for better treatment of low-wage restaurant workers, conducted a study on the payroll card experience of Darden Restaurants employees.40 Darden owns several well-known restaurant chains across the country, including Olive Garden and LongHorn Steakhouse. Roughly 48 percent of the company’s 140,000 hourly employees are paid through payroll cards.41 The 2016 study found that 76 percent of Darden employees using payroll cards reported paying ATM fees and that 24 percent reported paying point-of-sale fees. Moreover, 63 percent of employees reported that they were not told about all of the fees associated with the payroll card, and 26 percent reported that they did not have a choice between the payroll card and alternative wage payment methods. Darden employees reported paying fees for ATM use, the replacement of lost or stolen cards, and periods of account inactivity.42 Darden denied most of the report’s findings.43

Beyond these individual lawsuits and investigations, some broader studies have been conducted on payroll card fees and practices. In 2012, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia released a study conducted using hundreds of millions of transactions on 3 million prepaid cards—including payroll cards—issued by Meta Payment Systems.44 Based on the transaction analysis, the Philadelphia Fed found that the 20 percent of payroll card users that incurred the highest fees paid an average of $16 per month.45 While this may sound like a modest amount to spend, at the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour, it would result in more than 24 hours of gross earnings per year going directly to financial fees. Meanwhile, a higher-income worker with a bank account and direct deposit may incur no fees at all.

In 2014, the New York state attorney general’s office initiated a data collection on payroll card programs and published a report on the findings.46 Some of the employers who submitted data to the attorney general provided detailed information on the fees incurred by their workers. The information from this set of employers revealed that 70 to 75 percent of the payroll card users incurred a fee of some kind. The report also found that in some of the payroll card programs, the fees averaged as high as $20 a month per worker. Fees were particularly high for programs that charged overdraft fees, amounting to 46 to 63 percent of the fee revenue on some payroll card programs. In addition, the report found that workers were not receiving appropriately detailed and clearly written disclosures on the payroll card programs’ terms and conditions. Similarly, in 2014, the New Economy Project, the New York Public Interest Research Group, and Retail Action Project surveyed hundreds of workers in New York state. Of those surveyed, the 17 percent who were paid on payroll cards noted ATM fees, monthly maintenance fees, point-of-sale fees, declined transaction fees, and inactivity fees as the key fees they had incurred on their payroll cards.47

Prior to initiating the prepaid card rulemaking process in 2014, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) analyzed an array of prepaid card agreements, including those for payroll card programs.48 The analysis showed that at least 75 percent of payroll card programs charged a fee for accessing account information through a paper statement and that these fees ranged from $1 to as much of $5 per occurrence. Moreover, at least 12 percent of the payroll card agreements in the CFPB study had negative balance fees, and at least 12 percent of the card programs did not pass deposit insurance through to account funds in order to protect them in case of a bank failure. In 2018, nonprofit financial research institute CFSI released a survey of almost 700 payroll card users.49 Of those surveyed, 44 percent had incurred fees using their payroll cards. Within that subset that had incurred fees, 74 percent of the payroll card users reported paying fees at least once a week. Furthermore, 21 percent of those surveyed felt that they did not have a choice when it came to how they were paid.

Other studies that have focused on general use prepaid cards have shed light on the types of fees that are also present on payroll cards. Two studies by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City that were based on NetSpend data confirm that consumers who opt in to overdraft protection pay more each month for their prepaid cards.50

Clear, robust, and nationwide data on payroll card fees incurred by workers every year is not publicly available. As discussed in the recommendations section, that must change. The stories of workers who have sued their employers over these practices—in several cases, successfully—as well as the various state, nonprofit, and regulatory surveys conducted, demonstrate the risks posed by high fees. Some of the dollar amounts for the fees may not seem like a lot, but for low-wage workers, they quickly add up. These fees can amount to several hours of work a week. For workers, that could be the difference between making ends meet and falling even further behind. Moreover, there is evidence that workers are being pushed into these cards, even though federal law requires employees to be given a choice of payment methods.51

All told, the studies, investigations, and lawsuits suggest that a small but significant and growing percentage of workers are paid on payroll cards. Furthermore, a portion of these workers pay particularly high fees that can dramatically reduce their take-home pay.

Existing payroll card regulation

Payroll cards are regulated at the federal and state level and are governed by both labor and consumer protection laws. Before outlining what policymakers can do to improve the regulatory framework, it is first necessary to examine the current safeguards in place for workers using payroll cards. The provisions in place at the federal level provide some choice when it comes to how workers can be paid, and they primarily use disclosure to protect payroll card users. Some states have gone beyond the federal baseline, instituting bans on various payroll card fees and affording payroll card users additional protections.

Federal policies

Federal worker protection laws do not directly address payroll cards, but the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) contains several relevant provisions. The FLSA generally allows for electronic payment of wages, including payroll cards, as the law is relatively flexible on the manner in which workers are paid so long as it is “cash or negotiable instrument payable at par,” rather than company coupons or similar instruments.52 The FLSA also requires that workers be paid at least the minimum wage and that wages are received “free and clear,” meaning they are not subject to impermissible deductions that primarily benefit the employer—such as deductions to cover the costs of a required uniform.53 There is no formal guidance or interpretation from the Department of Labor about how the provisions apply to payroll cards, nor has the judiciary clarified these standards, as most cases have settled out of court. Yet according to current and former Department of Labor staff, these provisions of the FLSA have been interpreted to mean that payroll cards must allow workers at least one free complete withdrawal per pay period and that unavoidable fees cannot bring wages below the federal minimum.54 Violations of the minimum wage provisions are subject to monetary penalties, while violations of the “free and clear” standards are not. Under the FLSA, workers have a private right of action to go to court, and states may set higher standards.

The primary federal consumer regulations affecting payroll cards flow from the Electronic Fund Transfer Act (EFTA).55 This 1978 legislation provided consumers who receive an electronic transfer of funds with certain rights, including specific mandated disclosures, error resolution procedures, and a limited liability framework. The EFTA gave the Federal Reserve Board the authority to implement and enforce the bill’s provisions. Its implementing regulation is referred to as “Regulation E.” The protections of the 1978 legislation covered transfers to and from bank accounts, among other accounts. Payroll card accounts, which did not exist at the time, were not explicitly included in the initial set of EFTA covered accounts. In 2006, due to the increased use of these payment vehicles, the Fed finalized an amendment to Regulation E that extended the protections of the EFTA to payroll card users.56

When the Fed’s 2006 Regulation E amendments took effect in 2007, payroll card users began to enjoy the suite of EFTA protections. One of the pillars of the EFTA framework is mandated disclosure.57 Essentially, the financial institution issuing the payroll card must provide certain disclosures to card users when contracting to use the product or at least before the first fund transfer. Among other things, the payroll card issuer has to disclose the fees charged for electronic transactions or the right to make transactions.

In addition to disclosures, Regulation E included certain procedural requirements and afforded payroll card users with some limited protections. Under the regulation, financial institutions must provide payroll card users with limited liability protection for unauthorized transactions and have error resolution procedures in place. Payroll card users also have the right to either receive periodic statements that include their transaction history and fees paid during that time period or have access to that information electronically, with some requirements pertaining to the length of history that has to be displayed. In addition, Regulation E prohibits employers from dictating which financial institution will receive the electronic transfer of the employee’s compensation. This effectively means that employers cannot require employees to receive their compensation through a payroll card; they must offer an additional payment option. Typically, employers that offer a payroll card will offer direct deposit to a bank account of the employee’s choosing, but state employment law governs additional requirements around alternative payment options.58 The EFTA also affords consumers private rights of action, meaning they can sue in court over EFTA violations within one year of the violation.59

In 2009, the Fed again amended Regulation E and added a provision prohibiting financial institutions from providing overdraft services without the consumer’s consent.60 Overdraft services enable consumers to complete transactions when doing so would result in a negative account balance. The financial institution provides the funds to make up the difference. However, the fees charged for this type of credit service are notoriously high and, in some cases, have been attached to payroll cards without workers’ consent.

The 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank) created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau as an agency with the sole mission of looking out for consumers in the financial marketplace. In establishing the agency, Dodd-Frank transferred rulemaking and enforcement authority over the EFTA and Regulation E to the CFPB. The enforcement authority of the CFPB extends to financial institutions issuing cards, third-party service providers connected with the card program, and employers. Moreover, under Dodd-Frank, state attorneys general have the authority to bring civil cases against these institutions in order to enforce Regulation E and other rules promulgated by the CFPB.61

Mandatory arbitration limits private enforcement

While state and federal enforcement of these protections is crucial, it is not sufficient. Workers run the risk of being unable to bring claims against their employer privately in court due to the presence of forced arbitration clauses in either their employment contracts or in the contracts for financial products that provide their wages. Under these agreements, victims—often unwittingly—forfeit their right to pursue judicial remedies or to join class-action lawsuits in court. Instead, they must go through the private arbitration process, which limits their ability to obtain relief.62

One analysis estimated that about 1 in 3 private sector workers are subject to forced arbitration.63 Meanwhile, in a CFPB sample of card agreements, 44 percent of payroll cards contained mandatory arbitration language.64 That same study also found that 92 percent of general purpose reloadable prepaid cards—representing 83 percent of this market overall—required customers’ legal disputes to be resolved in arbitration rather than court.65 In 2017, the CFPB banned the use of forced arbitration clauses that prohibit class-action lawsuits in financial contracts, but the arbitration rule was struck down by Congress and President Donald Trump.66 In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court also upheld these forced arbitration agreements in employment contracts.67

In 2016, the CFPB exercised its rulemaking authority under Regulation E and finalized a rule that primarily expanded the coverage of Regulation E to prepaid card accounts, which include general use prepaid debit cards and other similar products.68 This rule is scheduled to take full effect in April 2019.69 As previously discussed, payroll cards were already covered by the EFTA’s requirements. The CFPB’s 2016 prepaid rule did affect payroll cards by enhancing some substantive elements of Regulation E, including the disclosure framework. The CFPB created a new short-form and long-form disclosure requirement that increased and clarified disclosures for payroll card users. The short-form disclosures create a format that is more standardized and easier to understand, while the longer-form document provides more in-depth detail on the payroll card program.

Beyond creating the new disclosure format, the 2016 rule expanded the number and types of fees that must be prominently disclosed to employees before they enroll in the payroll card program, including fees for ATM balance inquiries, customer service, and inactivity.70 The 2016 rule also required the short-form disclosure to include the two additional fee types—beyond the fees that are explicitly required to be disclosed on the short form—that generated the most revenue during the previous 24 months, if a certain revenue threshold was met.71 In addition, the rule improved the disclosure framework by establishing a requirement that employers either include a simple, straightforward statement that employees do not have to accept the payroll card offered by an employer or include a list of the various payment options offered. Furthermore, financial institutions are required to explicitly state whether the funds on the payroll card enjoy deposit insurance coverage.

While Regulation E does not generally limit fees, the new prepaid rule—which applies to payroll cards—along with interpretations of the previous payroll card rule, does affect some fees.72

The 2016 prepaid rule increased the timespan of online and written transaction history information that employees have the right to access. The old requirement was a 60-day history, whereas the 2016 rule requires 12 months and gives employees the option to request up to 24 months.73 The rule also revised the content of the transaction histories. Financial institutions must include all fees incurred by the payroll card account in the past calendar month and year to date. Moreover, payroll card agreements must be submitted to the CFPB. Additionally, in order to address overdraft concerns, the 2016 prepaid card rule added important new constraints on credit features linked to a prepaid card.

The changes in the CFPB’s 2016 prepaid card rule certainly improved the regulation of payroll cards but largely maintained the disclosure-centric regulatory approach. However, some states have gone much further than the federal government, banning or limiting certain practices and fees altogether.

In short, federal workplace and consumer laws allow workers to be paid on payroll cards as long as workers have free access to their money at least once a pay period, required fees don’t take wages below the federal minimum, certain disclosures are made, and workers have access to basic account information at no cost.

Federal requirements for payroll cards74

Fee disclosure: Yes

Card transaction history: Yes

Limited liability: Yes

Error resolution: Yes

Free withdrawals: One

Choice to receive a payroll card: Yes

Fee prohibitions: One75

Ban on credit features: No

FDIC pass-through insurance requirement: No

State policies

Regulation of payroll cards also occurs at the state level and varies significantly across states. Some states have additional protections above the federal floor, including bans on junk fees and stronger requirements for free cash withdrawals of payroll account funds. Unfortunately, too many states provide no additional protections above the federal base.

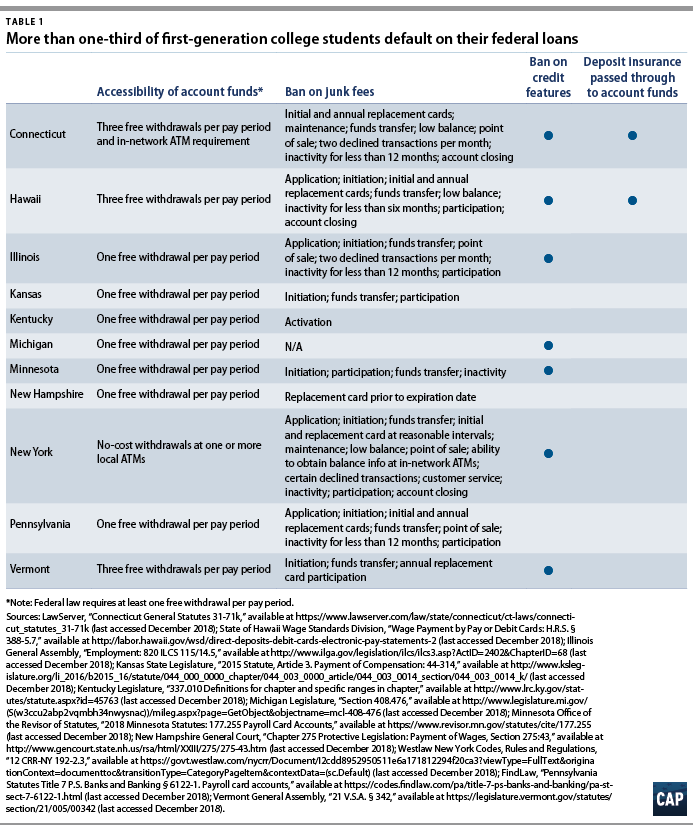

Currently, 39 states and the District of Columbia do not have rules in place that exceed federal baseline protections afforded by the EFTA and Regulation E.76 Seventeen of these states and the District of Columbia do not have explicit rules governing payroll cards, while the remaining 22 states have rules in place that largely reiterate federal requirements. The 11 states that exceed baseline federal requirements—Connecticut,77 Hawaii,78 Illinois,79 Kansas,80 Kentucky,81 Michigan,82 Minnesota,83 New Hampshire,84 New York,85 Pennsylvania,86 and Vermont87—have all enacted fee restrictions or other protections above the federal base.

Since the CFPB retooled and improved payroll card program disclosures in 2016, these 11 states have exceeded federal requirements in the four following areas: providing additional free access for fund withdrawals, banning junk fees, eliminating credit features, and requiring deposit insurance for account funds. Four of the 11 states—Connecticut, Hawaii, New York, and Vermont—provide more free access to account funds, beyond the one free withdrawal required by federal labor law. Connecticut, Hawaii, and Vermont also require payroll cards to offer three free withdrawals, while New York requires the payroll card to have access to an ATM network with free in-network withdrawals.88

Ten of the 11 states ban at least one junk fee, but there is some variation between states on how many fees, and which specific fees, are restricted. The most frequently banned junk fees include fees for account application, fund transfers, replacement cards, and inactivity. Five states—Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, New York, and Pennsylvania—ban at least seven payroll card fees. The mix of banned fees differs across these five states but includes the frequently banned fees listed above as well as fees for participation, maintenance, low balance, point-of-sale transactions in stores, some declined transactions, and account closing.

Seven of the 12 states—Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, and Vermont—effectively ban credit features such as overdraft services or payroll card-linked loan programs from being connected with payroll card accounts.89 Federal law only requires an affirmative consumer opt-in and does not ban credit features outright, although the new prepaid rule imposes limits on overdraft services and fees in the first year.90 In addition to an outright ban on credit features, some of these states have limits on fees for declined transactions. For example, Illinois bans fees on the first two declined transactions per month and requires reasonable fees for any additional declined transactions.

For example, Illinois bans fees on the first two declined transactions per month and requires reasonable fees for any additional declined transactions.

Finally, two states—Connecticut and Hawaii—require the federally insured financial institution issuing the payroll card to pass deposit insurance through to the individual account holder.91 The FDIC and NCUA have protocols in place to apply deposit insurance on an individual account basis for payroll card programs.92 Without this requirement, a financial institution could hold the payroll account funds in a master account that exceeds the $250,000 deposit insurance limit. Requiring financial institutions to follow the pass-through protocols is an important safeguard to eliminate the possibility of workers losing their payroll card funds if the financial institution fails.

Policy recommendations

Nonprofit groups and industry coalitions have done important work to encourage financial institutions and employers to voluntarily adopt best practices.93 Yet while these efforts have improved payroll card practices, it is time for state and federal policymakers to more consistently and fully use their authority in this area. There are several steps that policymakers can take to ensure that workers actually receive the full value of their paycheck. Legislation may be required for certain changes; yet other changes can be implemented by executive action, depending, in part, on what is allowed under law. Indeed, the sweeping payroll card rules implemented in New York were carried out through regulatory action.94 And local lawmakers can take action on several of the recommended policy steps without state or federal direction, including data collection and improving how they pay their own workers.

Policy recommendations

Collect better data: Federal, state, and local policymakers should collect and publish data on payroll card users, the fees they incur, and whether workers believe that they have a choice of payment options. These inquiries should be conducted on an ongoing basis and remain attentive to future changes in how workers are paid.

Improve protections for consumers: Policymakers should ensure that payroll cards are safe financial products that do not separate workers from their wages.

- Ensure access to account funds: Federal and state policymakers should require that payroll card programs offer at least three free withdrawals per pay period or unlimited free withdrawals from multiple in-network ATMs within close proximity to the employee’s place of business.

- Prohibit junk fees: Federal and state policymakers should ban junk fees altogether, including fees for account application or participation, card balance access at ATMs, funds transfers, account inactivity, maintenance, low balance, the issuance of an initial card and annual replacement cards, point-of-sale transactions, declined transactions, and account closing.

- Ban credit features: Federal and state policymakers should prohibit credit features—such as overdraft services and lines of credit—from payroll card programs.95

- Mandate pass-through deposit insurance: Federal and state policymakers should require that payroll card programs follow the protocols in place to apply deposit insurance coverage for individual payroll accounts.

Adopt best practices when paying government workers: Payroll cards used by the government to pay workers—both contractors and direct employees—should have low overall fees and no junk fees or credit features. Additionally, they should enable workers to easily access their money multiple times, or from an ATM network, without charge.

Strengthen enforcement efforts: Federal and state policymakers should provide adequate funding of enforcement agencies, engage in strategic enforcement of problem industries, and involve community and worker organizations to amplify enforcement efforts and minimize fears of retaliation. Policymakers should strengthen private rights of action for workers and consumers.

The above policy recommendations are explained in more detail below.

Collect better data

Policymakers must address the lack of detailed public data on workers who are paid through payroll cards, their actual ability to choose a payment method at work, and the fees they incur.

The CFPB should collect and publish data on fees from financial institutions that issue payroll cards in order to shine a light on these practices and put pressure on financial institutions to offer better products for workers. This public report should outline the total value of payroll card fees paid by workers; the breakdown of fees incurred by fee type, income, and demographic data on payroll card users; and the percent of payroll card users who believed that they had a choice in how they are paid. The report should also discuss the federal government’s use of payroll cards to pay federal contractors and employees, as well as fees associated with those cards. Furthermore, the CFPB should restore the proposed requirement that payroll card fee schedules be submitted to and posted online by the CFPB. However, if the CFPB, given its current leadership, refuses or fails to conduct such data collection, Congress could use its authority and tools to conduct or require a similar study.

Moreover, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) shares EFTA and Regulation E enforcement authority with the CFPB for nonbank companies within the FTC’s jurisdiction.96 Additionally, in recent years, the FTC has conducted some research and policy work on the EFTA, so it could play a useful role in data collection as well.97

Likewise, state and local governments should conduct data collection on payroll cards in their respective jurisdictions, including their use of these cards as employers. The CFPB, as well as state and local governments, should conduct broader studies on the evolution of how workers are paid and the potential risks associated with new electronic payment methods, beyond just payroll cards, as they emerge.

Improve protections for consumers

Through rulemaking or legislation, the federal government should significantly raise the baseline protections in place for payroll card users. Workers using payroll cards should be afforded at least three free withdrawals per pay period, including at out-of-network ATMs. As an alternative, workers should have access to unlimited free withdrawals at in-network ATMs, with several ATMs in close proximity to their place of work. While some cards offer multiple withdrawals at tellers, ATMs are far more convenient and are where workers are most likely to incur fees. Moreover, such regulation or legislation should ban an explicit list of payroll card fees. It is time that baseline protections move beyond simply disclosing junk fees and actually eliminate them. The specific fees banned by states such as Connecticut, Hawaii, and New York represent a good start. These include fees for account application or participation, card balance access at ATMs, customer service, fund transfers, account inactivity, maintenance, low balance, the issuance of an initial card and replacement cards annually, point-of-sale transactions, some declined transactions, and account closing. Furthermore, credit features—including overdraft services—should be banned from payroll cards.98 Prohibiting credit features outright would ensure that employees do not get trapped in a cycle of debt when using this financial product. Moreover, financial institutions issuing these cards should be required to follow the FDIC and NCUA protocols to pass deposit insurance through to individual accounts.99 This requirement would protect employee funds in case the financial institution fails.100

Currently, action at the federal level to strengthen these protections is unlikely, but states can and should pass payroll card legislation restricting these fees and practices for workers. The payroll card protections enacted in New York, Hawaii, Illinois, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and six other states that exceed current federal requirements provide a template for action. Financial institutions, and some employers, will likely push back against efforts to enact strong rules governing payroll cards. Still, this is a fight worth having. When excessive payroll card fees come out of workers’ paychecks, they are taken from the lowest-income families and go straight to powerful financial institutions’ bottom lines. Financial institutions do not need to charge junk fees or limit free access to account funds in order for these cards to be profitable. It is still a business line that banks will pursue, but workers—especially low-wage workers, who are more likely to be paid through payroll cards—deserve these protections to ensure that they keep more of their hard-earned wages. It is worth noting that in states such as Hawaii, where strong rules have been enacted, banks and employers are still offering payroll card programs.

Adopt best practices when paying government workers

If a worker paid by the government—whether a direct employee or a government contractor—opts for a payroll card, that card should have low overall fees and no junk fees or credit features. Additionally, it should enable workers to easily access their money from a number of locations without charge. A report from the National Consumer Law Center found that payroll cards used by Nebraska, Oregon, and Oklahoma met its best practices criteria by making it easy for workers to access their wages and use their cards without incurring fees.101 Cards used by these three states had no fees for accessing cash, making purchases, getting balances, calling customer service, or declining transactions; they even gave workers at least one free out-of-network withdrawal per pay period.102 Similarly, the Direct Express card used by the federal government to pay benefits to recipients who do not have a bank account allows many different kinds of transactions without a fee.103

It is important to note that different agencies within federal, state, and local governments may use different types of payroll cards, and therefore, it is best practice to ensure that all payroll cards used meet a baseline of required features.

Strengthen enforcement efforts

Though there is not adequate data to pinpoint the precise incidence of legal violations around payroll cards, it is highly likely that compliance is an issue.

Wage theft and other workplace violations are common, especially in low-wage workplaces.104 One estimate from the Economic Policy Institute indicates that wage theft through violations of minimum wage standards costs U.S. workers more than $8 billion annually.105 Because payroll cards are often used by low-wage workers, it is likely that employer violations of payroll cards laws are common. In addition, there are more specific signs that payroll card violations are likely to be problematic. For example, there have been a number of lawsuits alleging violations, and the legal regulations are often weak or unclear; some even lack financial penalties. Even when there are clear standards—such as federal law that affords workers choice in whether or not they are paid on payroll cards—evidence suggests that noncompliance exists and that workers are reluctant to come forward with claims about being forced into payroll cards.106

The following general strategies could improve enforcement: provide enforcement agencies with adequate funding; involve community and worker organizations in enforcement efforts in order to amplify these efforts and minimize fears of retaliation; and strengthen workers’ private rights of action so they can collectively go to court to enforce labor laws.107

For starters, the CFPB arbitration rule should be reinstated by Congress, as well as other provisions to restore consumers’ and workers’ day in court.108 This rule prohibited forced arbitration clauses, enabling workers to join class-action lawsuits against financial institutions.109 In 2017, Congress narrowly passed and President Trump signed a Congressional Review Act resolution striking down the rule.110 In addition, the Department of Labor must provide clear guidance for employers and employees on when payroll cards use results in FLSA violations; and Congress should attach monetary penalties to violations of FLSA’s “free and clear” standard. States that do not have clear standards on payroll cards should immediately move to address that problem.

Over the next several years, the burden of enforcement will likely fall on state agencies and attorneys general since the CFPB, under former acting Director Mick Mulvaney, rolled back enforcement activities, watered down settlements that were already underway, and showed no interest in aggressively using the authorities at his disposal. For example, in 2018, The Washington Post found that publicly announced CFPB enforcement actions declined by roughly 75 percent, compared with the average over the past few years.111 During her confirmation process, new CFPB Director Kathy Kraninger could not identify a single action taken by Mulvaney with which she disagreed.112 It is unlikely that the CFPB will live up to its mission during her tenure. States must fill this void.

Conclusion

As payment technologies in the broader U.S. economy have evolved and become increasingly electronic, so to have the methods by which workers are paid. More and more workers are receiving their compensation on payroll cards. These products certainly have benefits. They provide convenience, safety, and faster payments to those who might otherwise receive payment through cash or check. They can be an important means of integrating the unbanked into the mainstream financial system. These cards can also be a useful budgeting tool for workers and their families, serving as a complementary financial product to traditional bank accounts. But payroll cards come with risks as well. Junk fees, limited access to free withdrawals, and costly credit features can separate workers from their wages. The workers most often paid on payroll cards are the low-income workers who can least afford those charges.

Thus far, the federal government has taken a disclosure-centric approach to electronic forms of payment. That is to say, payroll card issuers must provide extensive disclosures and access to information. Yet costly fees and harmful practices are not banned outright. Several states have gone above these federal protections, paving the way for other states—and, hopefully, the federal government—to follow their lead. Beyond enacting enhanced protections for workers using these products, federal, state, and local policymakers should collect better data on payroll card users and the fees they incur; abide by best practices when using payroll cards to pay their own public workers or contractors; and step up enforcement efforts to protect workers.

This report covers payroll cards specifically, but as payment methods continue to evolve, the themes in this paper will extend to new payment products. Financial technology firms will almost certainly develop new, convenient, app-based payment products that look similar to payroll cards. The name and functionality of these payment vehicles may change, but the need to protect workers from high fees and preserve their choice will remain. Workers should have easy, cost-free access to their wages, period.

About the authors

Gregg Gelzinis is a research associate for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress. Gelzinis focuses primarily on financial institutions, financial markets, and consumer finance policy. His work has been quoted in The New York Times, The Washington Post, American Banker, and other publications. Before joining American Progress, Gelzinis completed his Master of Arts degree practicum at the U.S. Department of the Treasury in the Office of Financial Institutions. During his undergraduate career, he held internships at Swiss Re, the Federal Home Loan Bank of Atlanta, and in the office of Sen. Jack Reed (D-RI). Gelzinis graduated summa cum laude from Georgetown University, where he received a bachelor’s degree in government, a master’s degree in American government, and was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa Society.

David Madland is a senior fellow and the senior adviser to the American Worker Project at the Center for American Progress. He has written extensively about the economy and American politics on a range of topics, including the middle class, economic inequality, retirement policy, labor unions, and workplace standards such as the minimum wage. His book, Hollowed Out: Why the Economy Doesn’t Work without a Strong Middle Class, was published by the University of California Press in July 2015. Madland has a doctorate in government from Georgetown University and received his bachelor’s degree from the University of California, Berkeley.

Joe Valenti is the former director of Consumer Finance at the Center for American Progress, where he focused on consumer protection and access to safe and affordable financial products. He previously served as a Hamilton fellow at the U.S. Department of the Treasury; as a graduate intern at the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs under then-Chairman Christopher J. Dodd (D-CT); and in research and policy roles at the Aspen Institute and the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs. He has been quoted in publications including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Economist. Valenti has a Master of Public Policy degree from Georgetown University and received his bachelor’s degree from Columbia University, where he was a John Jay scholar.