As of November 2015, approximately 2 million Americans were out of work and looking for a job for 27 weeks or more. While long-term unemployment has fallen significantly after skyrocketing during the Great Recession, this decline has been far too slow and long-term unemployment still remains unusually high even though the recession officially ended in June 2009.

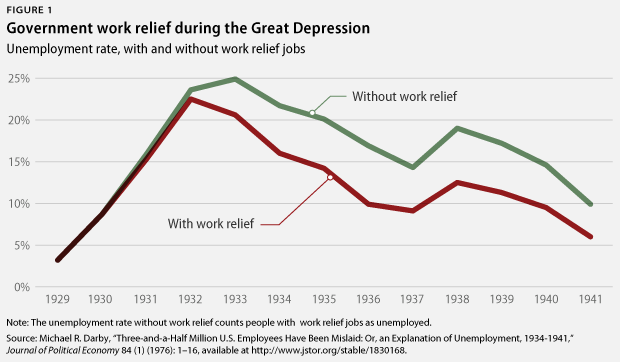

This enormous and ongoing waste of human and economic potential is by no means inevitable—and policymakers should take steps now to ensure that it does not happen again. As President Franklin Delano Roosevelt so rightly declared in 1934: “No country, however rich, can afford the waste of its human resources. Demoralization caused by vast unemployment is our greatest extravagance.” During the Great Depression, policymakers chose to implement what were dubbed work relief programs, such as the Civilian Conservation Corps, to dramatically reduce unemployment. In 1936, these work relief programs reduced the unemployment rate from 16.9 percent to 9.9 percent. The New Deal work relief programs not only put Americans back to work but also saw the building of countless public facilities—including parks, bridges, airports, and roads—that are still in use.

Americans continue to serve their country today in national service programs—such as AmeriCorps—that provide a modest living allowance and education awards for individuals who provide substantial service through programs that address national needs in fields including education, conservation, and affordable housing. These programs could also put Americans back to work in times of high long-term unemployment and provide a lasting legacy for future generations.

In 2009, Congress endorsed a significant expansion of national service by authorizing 250,000 AmeriCorps positions as part of the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act. But Congress never followed through with the necessary funding; consequently, AmeriCorps could only support approximately 73,600 positions in fiscal year 2014. Funding all 250,000 positions remains an important policy that should be implemented to strengthen national service regardless of economic conditions. Positions funded through AmeriCorps provide a foundation upon which high-impact national programs such as City Year, Reading Partners, and National Community Health Corps can grow; create opportunities for unemployed youth who are not enrolled in high school or college; and enable grassroots organizations in philanthropically underserved areas to offer positions directed at solving locally determined problems.

National service should also be expanded even further when the need is greatest. This report lays out a plan for a new funding stream for national service that automatically rises when long-term unemployment is high and falls when long-term unemployment is low. Unlike the 250,000 positions authorized by the Serve America Act, new positions created by automatic funding would be temporary and specifically designed to phase out when they are no longer needed as the economy returns to normal. This temporary service would be directed toward project-based work that can be completed on a short timeframe, such as projects targeting conservation and infrastructure, as well as efforts that address the human needs that increase during recessions. The federal government would partner with national service organizations to consistently maintain and update plans to create new positions on short notice to rapidly respond to a future rise in long-term unemployment.

Under this plan, national service would function as an automatic stabilizer. Automatic stabilizers, such as unemployment insurance and nutrition assistance, expand during recessions and contract during times of economic expansion. The need for assistance from the nonprofit sector is greatest when the economy is struggling, meaning that recessions are the perfect time to boost capacity with a surge of national service. Specifically, the plan would establish a formula for an automatic funding source that would support 25,000 new and temporary national service positions for every tenth of a percentage point by which the long-term unemployment rate exceeds 1 percent. The long-term unemployment rate has averaged about 1 percent from 1948 to the present, and no temporary positions would be created whenever long-term unemployment is at or below this historical average. The plan includes guardrails to ensure that national service is not expanded more rapidly than the system can support, and also to prevent economic shocks from withdrawing temporary positions too rapidly.

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, this policy would have responded decisively by supporting a peak of 475,000 temporary national service positions at a time when about 4.6 million people were long-term unemployed. If this automatic policy had been in place from fiscal years 2000 to 2014, it would have cost an average of $2.6 billion per year—enabling 1.87 million Americans to serve their country for a year during tough economic times and delivering a return on investment of $3.93 in benefits to society for every dollar spent based on an economic study of national service.

Expanding national service during economic downturns is a win-win-win: National service puts unemployed participants back to work, benefits the communities that participants serve, and helps grow the overall economy. This report describes the problem of long-term unemployment, how national service can put people back to work, and lays out a plan to mobilize the engine of service when it will deliver the most economic benefit.

America needs a substantial investment in national service. Policymakers should get started as soon as possible by setting and following through on a course to fully fund the 250,000 positions authorized by the Serve America Act, while also building the necessary capacity to implement a future temporary expansion. By establishing a system to automatically and temporarily expand national service to decisively respond to spikes in long-term unemployment, lawmakers can ensure that today’s service programs will alleviate future economic hardship and build a legacy for tomorrow.

Shirley Sagawa is a Visiting Senior Fellow at American Progress. Harry Stein is the Director of Fiscal Policy at the Center for American Progress.