The middle-class squeeze has produced a retail squeeze. Stagnant wages and increasing costs are not just hurting the nation’s middle class; their effects have now spilled over and are damaging the retail sector as well.

A recent Center for American Progress report showed that the median married couple with two kids in the United States made the same in 2012 as they did in 2000 after adjusting for overall inflation, but the growing cost of basic middle-class security—education, health, housing, and retirement—left the family with $5,500 less to spend on other needs. The Wall Street Journal similarly reported that slow income growth combined with the growing cost of middle-class security has reduced American spending in the middle 60 percent of the income distribution on clothing, furniture, appliances, and other consumer goods—even before adjusting for inflation.

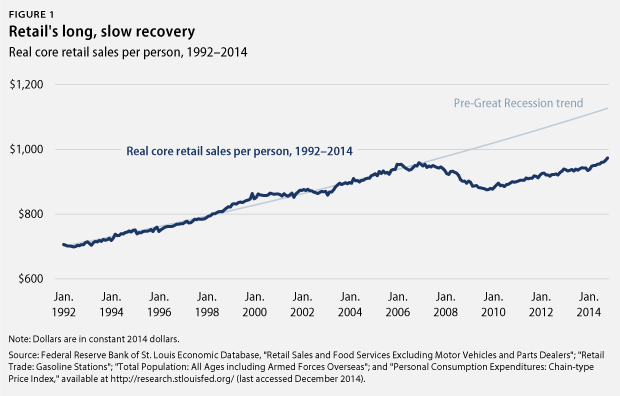

This squeeze on the middle class reduces their buying power and, as a result, hurts the retail sector. Core retail sales per person—retail sales minus auto and gas sales—took five years after the end of the Great Recession to reach their December 2006 prerecession peak. As of February 2015, core retail sales per person still stood 14 percent below their prerecession trend, costing retailers $51 billion in February 2015 alone. Wall Street giant Morgan Stanley blames poor consumer spending on meager wage growth:

So, despite the roughly $25 trillion increase in wealth since the recovery from the financial crisis began, consumer spending remains anemic. Top income earners have benefited from wealth increases but middle and low-income consumers continue to face structural liquidity constraints and unimpressive wage growth. To lift all boats, further increases in residential wealth and accelerating wage growth are needed.

Retailers themselves have confirmed their concerns about poor consumer spending. The Center for American Progress’ previous analysis of retailer U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, or SEC, filings found that 68 percent of retailers cite flat or falling disposable incomes as a risk factor to their stock price—double the percentage that cited this risk in 2006. When customers don’t have money, retailers don’t have customers.

But not every company’s customers are being squeezed: The top 1 percent has seen its real income rise by more than 15 percent between 2009 and 2013, and retailers that cater to these consumers have had a successful recovery. This report finds that the sales of retailers that appeal to high-income customers, such as Nordstrom, have grown much more quickly than the sales of retailers that target the middle class, such as the Gap Inc. and Target. Middle-class retailers are now following the money and trying to capture a larger portion of the 1 percent’s growing incomes: In 2013, for example, Gap bought luxury chain Intermix,and grocery giant Kroger acquired the high-end chain Harris Teeter.

But this is a retail adaptation rather than a retail recovery, which is what the U.S. economy needs. While some retailers may thrive in an economy where 76 percent of income growth goes to 1 percent of households,the retail sector as a whole will suffer because the rich cannot make up for the falling spending of the middle class. This is because the rich save more than the middle class does, suggesting that a smaller portion of their income gains translate into retail sales than middle-class income gains would. This report’s back-of-the-envelope calculations illustrate how equal income growth between 2009 and 2011 could have increased consumer spending growth by more than $45 billion, 11 percent faster growth compared to the actual consumer spending growth over that period. This is billions of dollars that could have been funneled back into the economy, helping boost the bottom lines of the retail sector and speeding up the sector’s recovery.

The only way the United States can launch a sustained retail recovery is if the middle class spends more, and for that we need public policies that will alleviate the middle-class squeeze. A middle-out retail agenda would increase middle-class disposable incomes—and retailers’ sales—by raising take-home pay through implementing progressive tax reform, reducing the student-loan burden through refinancing, and boosting workers’ wages through fair labor standards. The retail industry should actively support these and other measures that will help its most important customers—the middle class—jump-start a self-reinforcing cycle of consumer spending and hiring.

Brendan V. Duke is a Policy Analyst for American Progress’ Middle-Out Economics

project.