See also: “Infographic: The Hidden Dangers of 401(k) Fees” by Jennifer Erickson and David Madland

Less than one in five American workers in private industry has access to defined benefit pension plans. As a result, most Americans’ quality of life during retirement depends on whether they have invested in retirement savings vehicles such as 401(k)s and Individual Retirement Accounts, or IRAs, and how their investments perform. The reality is, the corrosive effect of high fees in many of these retirement accounts forces many Americans to work years longer than necessary or than planned.

Clearer, more transparent information has helped inform consumers about a variety of decisions from choosing between appliances to choosing between dinner options. With 52 million Americans relying on 401(k) funds as part of their retirement savings and a similar number depending on IRAs, why not offer better labeling for retirement funds?

All retirement funds should have a clear, understandable label that provides consumers with relevant, concise, and accessible information about fees. Improved fee disclosure could help individuals make better financial decisions—especially since data show that higher-cost funds do not necessarily perform better—and could encourage firms to provide lower-cost options. Perhaps most importantly, it could also force a national conversation about how to best improve our retirement system.

Fees are not the only problem with many private retirement plans. Indeed the Center for American Progress has proposed allowing all workers to save in the highly cost-effective 401(k) style plan: the government-employee Thrift Savings Plan. CAP has also proposed creating a new type of plan that combines the best elements of 401(k)s with the best elements of pensions to address the inherent weaknesses of self-directed retirement plans, as described at length in previous reports. But the impact of fees is critically important and can at least be addressed partly by better disclosure.

The problem of fees

There are two principal problems when it comes to retirement fund fees. First, they are often obscure or misunderstood. Second, they are often simply too high. It stands to reason that the more clarity there is on fees, the likelier it is that workers will choose lower-cost funds, especially since investors are not necessarily getting a higher return when they pay higher fees. In fact, a 2009 study found a negative relationship between fees and fund performance. But a central challenge is that even when fees are disclosed, the fees themselves can seem very small because the disclosures are not good enough at providing consumers the information they need to make an informed decision. Unfortunately, as Owen Donley, the chief counsel in the Security and Exchange Commission’s Office of Investor Education and Advocacy, recently pointed out, even fee percentages that may at first appear inconsequential “can have a very profound impact on investment returns” over time.

On average, American workers’ 401(k) plans charge fees of approximately 1 percent of assets managed—which covers fund-specific fees such as the expense ratio, as well as other administrative fees; IRA’s costs can be a bit higher. Even worse, many workers pay more. In fact, small-business employees typically face significantly higher fees: A 2011 study found that plans with fewer than 100 participants have an average fee of 1.32 percent.

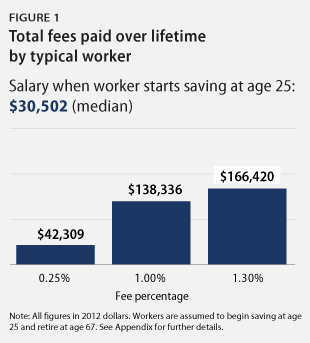

To understand how this affects an individual, consider, for example, that a worker has a choice of investing in a mutual fund with a total expense ratio of 25 basis points—0.25 percent, which is in line with available, low-cost retirement options—or another with fees of 100 basis points—1 percent. While the difference of 0.75 percent may sound small mathematically, the cumulative effects over time of that difference are huge.

Enter the power of compound interest. Assume this worker is 25 years old, earns the median income of $30,502 for workers in her age group, and saves 5 percent of her salary annually in a retirement plan, which in turn is matched by her employer for a 10 percent contribution amount. That seemingly small 0.75 percent difference would cost her almost $100,000 in fees over her lifetime, according to our calculations (see Appendix for more details about our calculations). To make up the difference caused by high fees versus low fees in her account balance by the time she retires, that worker would have to work more than three additional years. This means that saving in a retirement plan with average fees can force a worker to stay in their job years longer than they may have planned.

Adding to the issue is the fact that most workers spend little time selecting their 401(k) and IRA funds. So now imagine that same 25-year-old worker choosing a fund with 1.3 percent fees. Those numbers would jump to a whopping $124,000 in extra fees over her lifetime. For a two-income household, excess fees would strip away a quarter of a million dollars from their potential retirement savings.

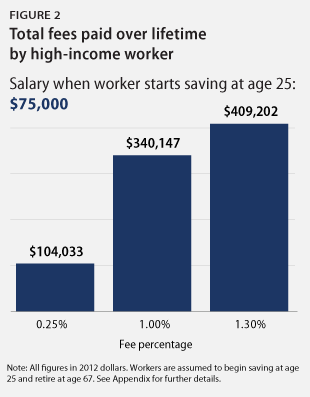

What about a worker in a similar situation earning $75,000 at age 25? Over the course of her lifetime, she would pay more than $300,000 more in fees if she were invested in the fund with 1.3 percent fees compared to the 0.25 percent fee fund. In fact, to make up the shortfall in her account by the time she retires, her total contribution—including both employer and employee contributions—would have to increase by 25 percent. Even worse, since employer contributions generally top out at or below 5 percent, she would likely have to increase her individual contribution to her retirement from 5 percent of her salary to 7.5 percent—a jump of 50 percent in her personal retirement savings each year for her entire working life.

The impact of these fees is so dramatic that it can strip away 20 percent or more of an employee’s retirement savings. In fact, according to simulations in an earlier Center for American Progress Action Fund report, the typical worker is able to achieve sufficient retirement income “69 percent of the time when fees are at 0.5 percent, 57 percent of the time when fees were 1 percent, 45 percent of the time when fees were 1.5 percent, and just 29 percent of the time when fees were 2 percent.”

At a time when our nation’s current personal savings rate is less than half of what it was 30 years ago, this strain to save more to cover fees is a huge problem. And given the fact that many older workers are having a difficult time staying in the workforce—with 47 percent of retirees in 2013 having retired earlier than planned—working longer to cover retirement fees may not even be an option.

Fees and performance

When it comes to the fees investors pay to participate in mutual funds—through their retirement accounts or other vehicles—the reality is that investors are not necessarily getting a better return when they pay higher fees.

In fact, Morningstar’s Director of Mutual Fund Research Russel Kinnel wrote:

If there’s anything in the whole world of mutual funds that you can take to the bank, it’s that expense ratios help you make a better decision. In every single time period and data point tested, low-cost funds beat high-cost funds.

Economists Javier Gil-Bazo and Pablo Ruiz-Verdú studied this phenomenon in their widely cited 2009 paper “The Relation between Price and Performance in the Mutual Fund Industry.” They actually found that “there is a negative relation between funds’ before-fee performance and the fees they charge to investors.” This paper furthered the 1996 research of NYU Professor Martin Gruber, former president of the American Finance Association, who found that “expenses are not higher for top performing funds.” Gruber also noted that “It has been suggested that management prices excellent performance by charging higher fees.” But “In fact this is not the case.”

One of the most common ways that funds achieve low fees is to track an index such as the Standards and Poor’s, or S&P. So what happens when funds are not actively managed and instead hew to an index of funds? The 2013 “S&P Indices Versus Active Funds Scorecard” found that, on average, actively managed funds—funds where managers choose their portfolio rather than track an index—did worse from mid-year 2012 to 2013 than S&P indices: “59.58% of large-cap funds, 68.88% of mid-cap funds and 64.27% of small-cap funds underperformed their respective benchmark indices.” This finding is even stronger on the three- and five-year time horizons: 78.9 percent of all domestic equity funds were outperformed by the S&P Composite 1500 over three years, and 72.14 percent were outperformed by that index over five years.

In fact, investor and Forbes columnist Rick Ferri found that from 1997 to 2012, “the index fund outperformed active funds 77.1% of the time.” Vanguard founder Jack Bogle has been outspoken about “the loser’s game of trying to beat the market” through actively managed funds. As Jack R. Meyer, former president of Harvard Management Company, said:

Most people think they can find managers who can outperform, but most people are wrong. I will say that 85% to 90% of managers fail to match their benchmarks… because managers have fees and incur transaction costs, you know that in the aggregate they are deleting value.

Better disclosure, better choices

In 2012, the U.S. Department of Labor, or DOL, implemented a rule requiring disclosure of 401(k) fees with the goal of ensuring that workers are given “the information they need to make informed decisions, including information about fees and expenses” to allow for a “new level of fee and expense transparency.” These disclosures include a requirement for plan administrators (employers) to inform participants (employees) about the structure of the plan, a list of investment options with historical returns compared to benchmarks, and information about fees and expenses. They also require quarterly statements to show participants how much they were charged in fees.

These disclosures are an important step forward, as fee disclosure to participants was voluntary under section 404(c) of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, or ERISA, prior to this rule. The rule appears to have made some impact: A 2013 study by LIMRA, a financial industry research association, showed that 38 percent of 401(k) participants thought they paid no fees in 2012, while this number dropped to 22 percent in 2013. However, even after the new disclosures began, half of participants still said they do not know how much they are paying in fees.

The disclosures may also be having a small impact on plan sponsors (employers). Cogent Research found that 51 percent of plan sponsors intend to change investment options over the next year, compared to 44 percent in 2012, with the report’s lead author attributing the increase to increased disclosure. DOL took another step toward clearer disclosure with a proposed March 2014 rule requiring service providers that “make their disclosures through multiple or lengthy documents to furnish a guide to such documents.” This is incredibly important because while clear disclosures can help employees make better-informed choices between funds, the current flawed system still requires them to choose from the funds their employer makes available to them in a given 401(k) plan, leaving employees to bear the burden of plan sponsors’ bad choices.

The lesson here is that for investors to understand the impact of their choices, more disclosure is not the complete answer. What is required is better disclosure. Currently, some disclosures contain more than 30 pages, overwhelming consumers with detailed information that is difficult to navigate.

Following the advice of our colleague, economist and CAP Senior Fellow Christian Weller, we believe that financial disclosures should be:

- Concise: brief and easy to navigate.

- Accessible: prominently displayed on all retirement fund materials.

- Relevant: highlighting key cost information in a way investors can understand.

What follows are how these principles can be applied to informing investors about the fees in their IRA and 401(k) plans and the individual funds they chose.

Concise

Consumers are used to receiving—and often ignoring—dense disclosures about products that they buy. Buying music on the internet or registering for a new telephone plan can offer pages and pages of legal information, to say nothing of more weighty financial decisions such as choosing which funds to invest in for retirement. An ING study showed that their Canadian customers spent significantly longer researching which smartphone to buy than which mutual funds to invest in. In the United States, workers spend more time annually planning for vacations and the holidays than planning for their retirement, with 39 percent of workers reporting that they spent no time in the past year planning for retirement. If these numbers tell us anything, it is that brevity and consistency are likely to be virtues.

Accessible

As concise as a disclosure is, if it is not easily accessible during the limited time many Americans spend planning for their retirement, then it will not be valuable. Disclosures have already moved from being available on written request to being mandated quarterly. While that is an improvement, in a world where data can be so easily available and provided, disclosures about something as fundamental to a product as its fees should be readily visible on all materials, with the same level of ubiquity that we see with nutritional labels on food and warning labels on cigarettes.

Relevant

Even if they are concise and accessible, financial disclosures will be of limited value if they do not provide relevant information for consumers.

One of the problems with current fee disclosures is that they do not give investors useful comparisons. As discussed in the earlier example of a typical investor, seeing that one fund has a fee of 0.25 percent and another of 1 percent does not reveal the full scope of the cost difference between two funds. Viewing what, in effect, appears to be two small numbers obscures the effects of compounding over time.

Other disclosures similarly mute the dramatic effects of compounding. For example, the Department of Labor’s Model Comparative Chart, which discloses the fees associated with investing $1,000 for one year, makes the fee difference of expense ratios look like a few dollars instead of the hundreds of thousands of dollars it could easily translate to over time.

To provide more relevant information about the true cost of fees, disclosures should show a fund’s fees compared to similar funds that are low cost. So, for example, when a consumer is choosing an IRA that will invest in large equity funds, the relevant cost disclosure should be how the fees associated with one fund compare to the lowest 5 percent of similar funds. In fact, private companies such as Morningstar already compare fees of similar funds.

The goal is to provide the consumer with the relevant information they need to make a choice. This means that these comparisons will be based on the fees that the consumer has control over and thus may be slightly different for IRAs than for 401(k)s.

Learning lessons from labeling

The government has created labels for a number of products—from food to appliances to cigarettes—that have helped inform consumers and influence behavior, indicating that our proposed fee label could be quite successful.

In 1993, the Food and Drug Administration, or FDA, introduced the Nutrition Facts label. Today’s consumers often rely on this label, with 77 percent of Americans reporting that they use nutrition labels “sometimes” or “often” when buying food products for the first time. Consumers have also been shown, both in real-world restaurant and laboratory settings, to eat fewer calories when nutrition labeling is available. Importantly, better disclosure could also potentially improve the menu of choices consumers face. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s, or USDA’s, Economic Research Service noted that food producers created healthier food in response to the introduction of the Nutrition Facts label.

The Environment Protection Agency’s, or EPA’s, Energy Star label provides consumers with energy-use information for products such as televisions, as well as commercial buildings by comparing products to energy-use baselines. A 2012 EPA survey found that 87 percent of American households recognized the Energy Star label, and about 40 percent knowingly purchased an Energy Star-labeled product in the past year. Not only is the label clearly recognized, it has also been found to save consumers money and reduce energy use. According to EPA analysis, EPA’s Energy Star efforts helped consumers save $26 billion on energy bills and reduced electricity demand by 5 percent in 2012. This makes clear that even though Energy Star labels should be updated to reflect technological advance, they have had some notable success.

Another example of public health labeling comes from the 1965 Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act, which required the following health warning to be placed on all cigarette packages sold in the United States: “Caution: Cigarette Smoking May Be Hazardous To Your Health.” While concurrently implemented public health initiatives make it difficult to attribute the precise effect of cigarette warning labels on behavior, we do know that 47 percent of Americans see warning labels as a source of health information. Additionally, research on the cigarette labels suggests that simple, straightforward messages are more effective for communicating risk.

These examples highlight that when disclosures are concise, accessible, and relevant, they can be successful in changing behavior and product offerings. We see some of these principles implemented in the FDA’s newly proposed Nutrition Facts label update, which increases the prominence of calories and serving size information to better attract consumers’ attention. Just as nutrition labeling has informed consumer decision-making and encouraged the creation of healthier products, retirement fund labeling would help investors make smarter choices and potentially improve the quality of their choices.

A Retirement Fund label

Applying the principles that disclosures should be relevant, concise, and accessible, we can imagine a simple “Retirement Fund label.” A Retirement Fund label would be a box visible on all literature, either printed or web-based, that offers a simple disclosure that acts as a sort of hybrid of a cigarette warning and a nutrition label. This label would both inform consumers about the risk of high fees, while offering them a clear and comparable way to think about their fund options. For example:

The message is simple. At less than 25 words, it offers investors the relevant information that they need to compare funds by showing fees as a multiple of a benchmark of known low-fee funds. To make it more readily comparable and easily identifiable and to avoid information overload, the label should be standardized—thus avoiding the potential data creep that has plagued other disclosures. And it should be prominently displayed on all materials, including and especially those available when consumers are choosing their retirement options: when new employees are enrolling in a 401(k) plan, rolling 401(k) assets into an IRA, and signing up for an IRA for the first time, as well as when employers are setting up 401(k) plans. In this way, investors will see the Retirement Fund label when they are making critical decisions about retirement, as well as when they are reviewing their quarterly statements.

One can imagine four effects of this style of warning prominently displayed:

- First, it will help educate investors on a simple, critical metric, leading investors to think more about fees as a part of their investment decision.

- Second, it could lead plan sponsors (employers) to switch their offerings to include lower-fee funds as well.

- Third, it could lead retirement fund providers to lower their fees to avoid unflattering comparisons given heightened competition and scrutiny.

- Fourth, by highlighting such a blatant failing of the current retirement system, it may foster conversations about the broader changes that are needed to ensure that all Americans can have a secure and dignified retirement.

Some of these outcomes are already occurring because of the DOL’s 2012 rule, but improved disclosure would multiply the impact. We believe the fee label is a critical disclosure for policymakers to implement and should not be watered down by complicated or confusing additional disclosures. Otherwise, consumers will be overwhelmed by disclosures and not know what to focus on.

That said, there are two straight-forward disclosures separate and distinct from the fee label that could be valuable to consumers: lengthening the time horizon showing the effect of fees and offering clear comparisons for workers considering 401(k) to IRA rollovers.

First, lengthening the time horizon to show the effect of fees would better reflect long-term costs. Instead of only showing the impact of fees on $1,000 over one year, we could imagine a more relevant 20/20 disclosure, showing the impact of fees on $20,000 over 20 years. These balances and time horizons more accurately show the effect of fees on typical accounts.

Second, as part of the welcome, broader push to inform workers of costs and implications of rolling over their 401(k)s into IRAs, there should be a comparable fee benchmark that will allow individuals to compare their options. For example, if plan sponsors were required to show workers at the point of their separation from employment the total fees on each $20,000 invested over 20 years (whether their balance is $5,000 or $50,000), and IRAs were required to do likewise per the 20/20 disclosure described above, then there would be a clear point of comparison before workers make a potentially costly decision to move their money without clear and sufficient information.

Requiring these types of simple disclosures would be a market-based solution to the thorny and frequent problem of high fees eroding retirement savings and low information often leading to suboptimal decision-making. This simple Retirement Fund label would usher in an era of more useable information on retirement savings and would likely spur more competition in the marketplace for lower-fee funds. Although some will argue that the government does not need to help the market in this way, we believe that both the scope of the retirement problem, as well as the tax subsidies that are provided for retirement savings, necessitate action. Tax preferences should promote retirement security, not subsidize unnecessarily high fees.

Conclusion

In his 2014 State of the Union address, President Barack Obama called out the need to “do more to help Americans save for retirement.” And when the president spoke about the challenges facing millions of Americans in August 2013, he cited “secure retirement” as a “cornerstone of what it means to be middle class in this country.” To be sure, making retirements secure will involve myriad policy changes from the tax code to our system of social insurance. After all, millions of Americans do not have the option to invest in 401(k) plans because their employers do not offer such plans, nor the financial resources to invest in other vehicles.

But perhaps one of the simplest ways to start helping families build for secure retirement is by helping them to better understand their choices in retirement funds.

Americans have more than $10 trillion invested in IRAs and 401(k) plans. Clear information that can help workers and employers make better choices about investment options is a critical step in ensuring more men and women have a stable and secure retirement.

Jennifer Erickson is the Director of Competitiveness and Economic Growth at the Center for American Progress. David Madland is Managing Director for Economic Policy at the Center.