The Budget Control Act calculates the size of the sequester cut by subtracting the debt reduction produced by the super committee from a base of $1.2 trillion. Since the super committee failed to produce a bill, that leaves a full $1.2 trillion sequester to be implemented over nine years. But whether the fiscal cliff deal was produced by the super committee or not, it still delivered more than half of the debt reduction required by the Budget Control Act’s sequester provision. All Congress needs to do is amend the Budget Control Act to include the debt reduction from the fiscal cliff deal in the sequester calculation.

Subtracting the fiscal cliff savings of $737 billion from the $1.2 trillion sequester base leaves $463 billion of sequester cuts. The remaining sequester cuts will also yield extra savings by reducing the national debt, and therefore the interest that must be paid on that debt. To account for that extra savings, the sequester law reduces the overall amount of program cuts by 18 percent. Finally, the sequester law spreads those cuts over nine years, and then splits each year’s cuts evenly between defense and nondefense programs.

When the fiscal cliff savings are included in the sequester calculation, the annual amount of sequester cuts falls from $109 billion to $42 billion. That reduces the defense and nondefense cuts from $55 billion to $21 billion. Reducing the defense sequester gives the Pentagon flexibility to draw down national security spending in a responsible and strategic manner. But the benefits of applying the fiscal cliff deficit reduction to the sequester are even greater on the nondefense side.

The nondefense sequester is not allocated evenly within the domestic budget. Fortunately, many programs that form the foundation of American retirement security and the social safety net are protected completely, such as Social Security, Medicaid, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, commonly known as food stamps. Medicare and some other federal health programs are also partially protected by limiting the sequester cuts to 2 percent. Any sequester cuts that exceed this 2 percent threshold are reallocated to the rest of the domestic budget, meaning extra cuts. As a result, the sequester has made particularly deep cuts to investments in education, scientific research, and infrastructure, which fall into the broad category of nondefense discretionary spending.

Since the nondefense discretionary budget is hit hardest by the nondefense sequester, it also benefits most from reducing the sequester. If the fiscal cliff savings are included in the sequester calculation, the nondefense sequester becomes an across-the-board cut of 1.82 percent. That delivers a small amount of relief to Medicare, but Medicare cuts were already limited to 2 percent. The biggest impact is in the nondefense discretionary budget. While the sequester is currently set to cut about $37 billion from nondefense discretionary spending, accounting for the fiscal cliff savings reduces the sequester cuts to $9 billion.

Accounting for the savings in the fiscal cliff deal reduces the nondefense discretionary sequester by 75 percent, while the overall sequester is reduced by 61 percent. That means Congress can allocate $28 billion to prevent more cuts to job training, schools, transportation, and wherever else those funds are most needed within the nondefense discretionary budget to get our economy back on track.

(Click here to view the four tables in the issue brief.)

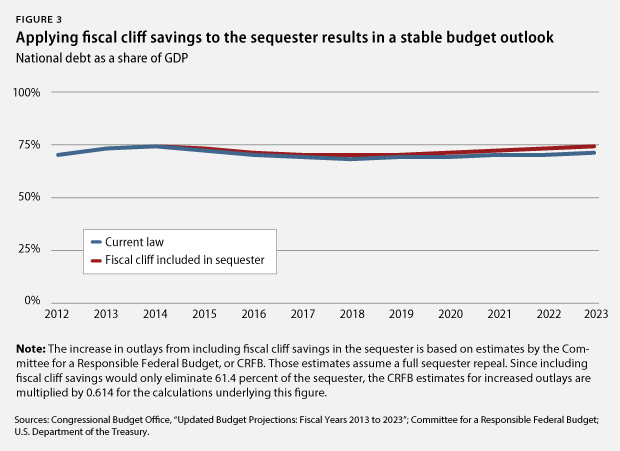

Applying fiscal cliff savings to the sequester results in a stable budget outlook

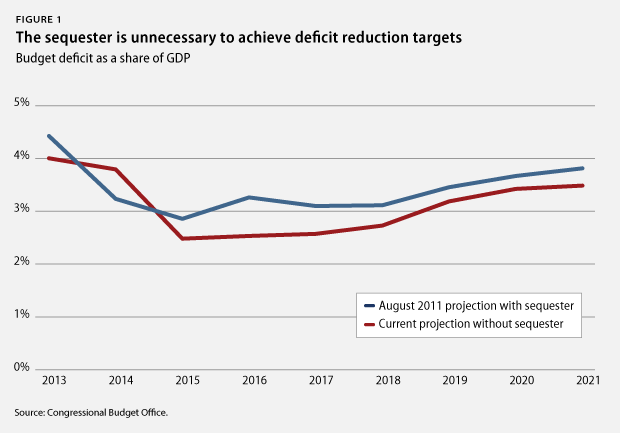

When the sequester was originally passed, Congress was confronting alarming projections of exploding national debt. That is no longer the case. According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget’s “realistic baseline”—which assumes a full repeal of the sequester without offsetting deficit reduction—the national debt will be lower as a share of the economy 10 years from now than it is today.

Debt projections are actually lower today without the sequester than they were with the sequester back in 2011. That is partly because the fiscal cliff deal reduced deficits by $737 billion over 10 years, and partly because of progress controlling the growth of health care costs. The Congressional Budget Office now estimates that spending for federal health care programs will be $672 billion lower from 2013 to 2022 than their earlier estimate from January 2012, primarily due to savings in Medicare and Medicaid. Additionally, premiums are coming in lower than expected for private health insurance sold through the marketplaces established by the Affordable Care Act, which the Center for American Progress estimates will reduce government spending by $190 billion over the next 10 years. Altogether, that totals about $1.6 trillion in deficit reduction since the Budget Control Act was passed—far exceeding the $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction from sequestration. In short, we no longer need sequestration.

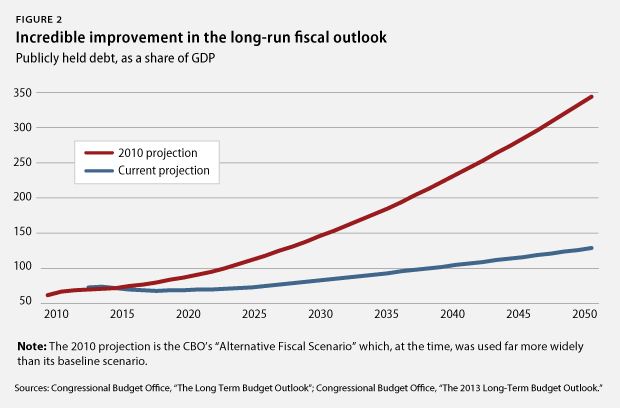

The long-term budget outlook has also improved dramatically. Back in 2010, the Congressional Budget Office’s most commonly used budget projection estimated that debt would approach 350 percent of our total economic output by 2050. Today, the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of debt as a share of the economy in 2050 is closer to 125 percent.

Applying fiscal cliff savings to the sequester maintains this stable budget outlook. Under this policy, the national debt would decline as a share of the economy over the next few years. In 10 years, the debt would equal approximately the same share of the economy as it does today.

There is still some work to do on the long-term budget, but this is not an immediate crisis. And sequestration, which expires in 2021, does little to address the long-term debt anyway.

Conclusion

The sequester is solving a short-term budget problem that no longer exists. Congress passed the sequester in the face of deeply concerning national debt projections, but those projections look much better now. One major reason for that improvement is the fiscal cliff deal. Using the fiscal cliff savings to reduce the sequester is exactly in line with Congress’s initial intent to replace sequester with smarter debt reduction.

Most importantly, scaling back the sequester enables Congress to focus on the very real economic crisis that we have now. More than 7 percent of Americans are actively looking for work but cannot find a job. Many more Americans are underemployed, and families everywhere are struggling to make ends meet. That is the crisis on which Congress should be focused. Reducing the sequester is a step in the right direction, but it is not enough. Rebuilding the economy will require a full repeal of the sequester and renewed investments to lay the foundation for long-term prosperity.

Harry Stein is the Associate Director for Fiscal Policy at the Center for American Progress.