The U.S. economy is in its fourth year of a moderate recovery. That is actually remarkable, considering that we have never before had a recovery in which state and local government spending and employment declined over three years, household debt remained higher than 100 percent of after-tax income, and the housing market did not grow substantially. And U.S. exports—often a key contributor to a recovery—have faced substantial headwinds from the European financial crisis and, more recently, slowing growth in China and India. Putting it differently, the economy and the labor market are still expanding because policymakers have regularly intervened with targeted policies.

The lesson for the future is twofold. First, smart and targeted policies can make a difference. Examples of these are policies that boost manufacturing and construction through infrastructure spending and aid to struggling states to keep teachers employed. Second, President Barack Obama and Congress have shown that they know how to strengthen a struggling recovery—largely because we have avoided another recession, thanks to recent policy interventions.

But the factors that have slowed the recovery—the crushing household debt burden, states’ financial troubles, a slow housing recovery, and the overseas crises—are still with us, and, in some cases, have even become worse. Policymakers need to keep the momentum going instead of stalling it by, for instance, letting the economy go over the “fiscal cliff”—the simultaneous expiration of tax cuts coupled with the onset of automatic spending cuts scheduled to go into effect at the end of this year. We should also build on our past record with targeted initiatives that keep teachers and other key public employees in their jobs, invest in key industries such as manufacturing and construction, and help the middle class escape a still-crushing mountain of debt.

1. Economic growth remains positive but modest. Gross domestic product grew at an annual rate of 1.3 percent in the second quarter of 2012. Government spending actually fell by 0.7 percent and business investment grew by 3.6 percent in the same time period, while consumption grew by 1.5 percent and exports expanded at a reasonable 5.3 percent growth rate. Government spending cuts reflect the continued fiscal crisis among federal, state, and local governments. The reasonable business investment and export growth rates were not enough to overcome lackluster consumption and shrinking government spending.

2. Competitiveness stays back. Worker productivity—the amount of goods and services produced in an hour of work in the nonfarm business economy—is a key measure of the economy’s global competitiveness. Productivity is now 7.4 percent greater than it was in December 2007, at the start of the Great Recession. This is below the average increase of 8.5 percent for similar periods in the past.

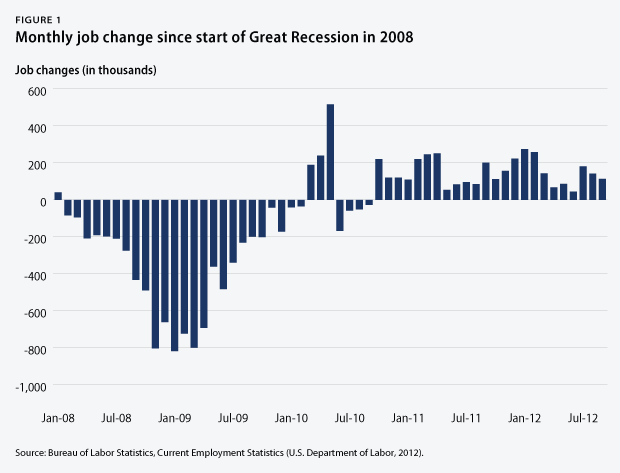

3. The moderate labor market recovery continues in its fourth year. There were 3 million more U.S. jobs in September 2012 than in June 2009, when the economic recovery officially started. The private sector added 3.6 million jobs during this period. The difference between the net gain and private-sector gain is explained by the loss of 568,000 state and local government jobs, as budget cuts reduced the number of teachers, bus drivers, firefighters, and police officers, among others. Job creation is a top policy priority since private-sector job growth is still too weak to quickly overcome other job losses and to rapidly lower the unemployment rate.

4. Suffering of the unemployed remains high. The unemployment rate stood at 7.8 percent in September 2012. Long-term unemployment remained high, however, even as the unemployment rate dropped: In September 2012, 40.1 percent of the unemployed were still out of work and had been looking for a job for more than six months. The average length of unemployment remained high, standing at 39.8 weeks in September 2012. Those out of a job for a long time are struggling because job growth has proceeded at a slow place. Millions of unemployed workers, therefore, are vying for the newly created jobs.

5. Labor market pressures fall especially on communities of color, young workers, and those with less education. In September 2012 the African American unemployment rate remained well above average at 13.4 percent. The Hispanic unemployment rate was 9.9 percent, and the white unemployment rate was 7 percent. Youth unemployment stood at a high 23.7 percent. And the unemployment rate for people without a high school diploma stayed high at 11.3 percent, compared to 8.7 percent for those with a high school diploma, 6.5 percent for those with some college education, and 4.1 percent for those with a college degree. Vulnerable groups have struggled disproportionately more in the weak labor market than white workers, older workers, and workers with more education.

6. Household incomes continue to drop amid prolonged labor market weaknesses. Median inflation-adjusted household income—half of all households has more and the other half has less—stood at $50,054 in 2011, its lowest level in inflation-adjusted dollars since 1995. It fell again by 1.5 percent in 2011—its fourth drop in a row. After 2009 American families experienced no income gains during the current economic recovery, exacerbating their losses during the Great Recession.

7. Income inequality is rising. Households at the 95th percentile, with incomes of $186,000 in 2011, had incomes that were more than nine times—9.2 times, to be exact—the incomes of households at the 20th percentile, which had incomes of $20,262 in 2011. This is the largest gap between the top 5 percent and the bottom 20 percent of households since the U.S. Census Bureau started keeping record in 1967.

8. Poverty remains high. The poverty rate fell to 15 percent in 2011, down from 15.1 percent in 2010. The African American poverty rate was 27.6 percent; the Hispanic rate was 25.3 percent; and the white poverty rate was 9.8 percent in 2011. The poverty rate for children under the age of 18 stood at 21.9 percent. More than one-third of African American children (38.8 percent) lived in poverty in 2011, compared to 34.1 percent of Hispanic children and 12.5 percent of white children. The prolonged economic slump, following an exceptionally weak labor market before the crisis, has taken a massive toll on the most vulnerable.

9. Employer-sponsored benefits disappear. The share of people with employer-sponsored health insurance dropped from 59.8 percent in 2007 to 55.1 percent in 2011. The share of private-sector workers who participated in a retirement plan at work fell to 39.5 percent in 2010, down from 42 percent in 2007. Families have less economic security than in the past due to fewer employment-based benefits, requiring more private savings to make up the difference.

10. Family wealth losses linger. Total family wealth is down $11.2 trillion (in 2012 dollars) from June 2007—its last peak—to June 2012. Homeowners on average own only 43.1 percent of their homes, with the rest owed to banks. Homeowners feel pressure to save more and consume less in order to rebuild their equity; this has slowed consumer spending and held back economic growth.

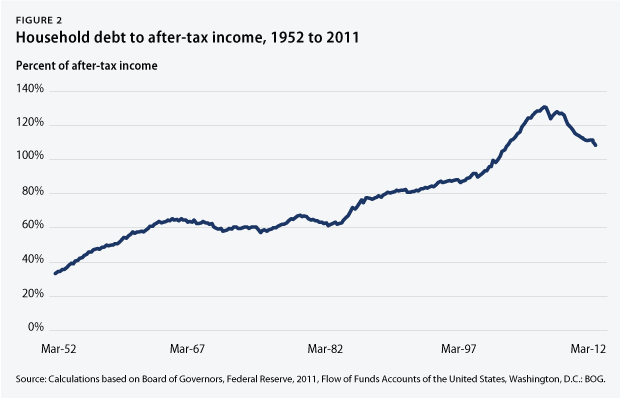

11. Household debt is still high. Household debt equaled 108.5 percent of after-tax income in June 2012, down from a peak of 129.3 percent in September 2007. The unprecedented fall in debt over the past four years resulted from tight lending standards, falling interest rates, massive foreclosures, and increased household saving. Further deleveraging will likely slow unless incomes rise faster than they have in the past. High debt could hence continue to slow economic growth as households focus more on saving than on spending.

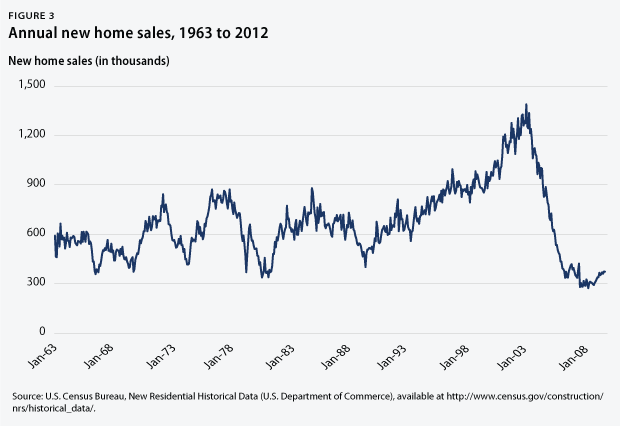

12. The housing market is finally and slowly recovering from historic lows. New home sales amounted to an annual rate of 389,000 in September 2012, up from 306,000 in September 2011 but well below the historical average of 698,000 before the Great Recession. The median new house price in September 2012 was 11.7 percent higher than a year earlier. Existing home sales were up by 11 percent in September 2012 from a year earlier, and the median price for existing homes was up by 11.3 percent during the same period. The housing market has a lot of room to grow and to contribute to economic growth since the spring 2012 recovery started from historically low home sales and since the housing market fell throughout most of the recovery.

13. Homeowners’ distress remains high. Even though mortgage troubles have generally eased since March 2010, one in eight mortgages are still delinquent or in foreclosure. The share of mortgages that were delinquent was 7.6 percent in the second quarter of 2012. The share of mortgages that were in foreclosure was 4.3 percent during the same time period. Many families delayed or defaulted on mortgage payments amid high unemployment and massive wealth losses. Banks, as a result, are nervous about extending new mortgages, prolonging the economic slump.

14. Near precrisis peak profits are not reflected in investment data. Inflation-adjusted corporate profits were 84.6 percent larger in June 2012 than in June 2009, when the economic recovery started. The after-tax corporate profit rate—profits to total assets—stood at 3 percent in June 2012, near the previous peak after-tax profit rate of 3.2 percent prior to the Great Recession. Corporations used their resources for purposes other than investments in plants and equipment. The share of investment out of GDP stayed low, standing at 10.4 percent in the second quarter of 2012.

Christian E. Weller is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress and an associate professor in the department of public policy and public affairs at the University of Massachusetts, Boston.