Download this issue brief (pdf)

Read this issue brief on your browser (Scribd)

The ongoing housing crisis remains one of the biggest drags on our economic recovery. But less than three months before a presidential election viewed by many as a referendum on the economy, housing is little more than a side conversation on the campaign trail.

President Barack Obama has barely mentioned housing in recent months, aside from occasional pitches for reforms to help more homeowners refinance. Presumptive Republican nominee Mitt Romney’s 59-point economic plan unveiled last year makes only a couple of passing references to housing, and Gov. Romney is yet to release any substantive housing proposals since.

As our presidential hopefuls stay silent, the sluggish housing market continues to plague our economy. The historic decline in home prices since 2006 has cost Americans more than $7 trillion in household wealth, forced millions of families out of their homes, and left nearly one in four homeowners owing more on their mortgages than their homes are worth. Private investment in housing is a fraction of its historic norm, translating to billions in lost economic output and millions of missing jobs. And more than five years into the crisis, the U.S. mortgage market remains on life support as the federal government guaranteed more than 95 percent of home loans made last year.

The U.S. housing market is where the Great Recession began and we’re unlikely to see a full recovery until the market heals. The housing sector historically accounts for about one-fifth of our economy and housing booms paved the path to our last three economic recoveries. But few analysts expect such a boom anytime soon.

We can no longer afford to ignore these problems. As the presidential campaign shifts into high gear in the coming weeks, President Obama and Gov. Romney must lay out their respective visions for housing in the United States. This brief lays out seven essential questions the presidential candidates need to answer on housing, including:

1. What will you do to prevent more unnecessary foreclosures and keep more families from losing their homes?

2. How will you address the problem of “underwater” mortgages?

3. How will you revitalize communities already hit hard by the foreclosure crisis?

4. How will you meet the pressing need for affordable rental housing?

5. What will you do to assure that working and middle-class families can achieve homeownership in the future?

6. What do you plan to do with the government-backed mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and what will take their place in the mortgage market of the future?

7. How do you plan to protect households from predatory lending and discrimination in the U.S. mortgage market?

Each question includes key facts for voters, reporters, and other key stakeholders, as well as a brief discussion of why the issue matters and CAP’s recommendation for fixing the problem.

1.Five years after the housing bubble burst, experts suggest we may be only halfway through the resulting foreclosures, with millions still to come. Do you think the federal government should do more to help prevent unnecessary foreclosures? If so, how?

Fast Facts

- As of March 2012, banks and other financial institutions had completed approximately 3.5 million foreclosures since the financial crisis began in September 2008, with another 1.4 million loans still in the foreclosure process. That month Wall Street analysts predicted as many as 7.4 million to 9.3 million at-risk borrowers were yet to face foreclosure or liquidation.

- Roughly 25 percent of African American and Latino borrowers have either lost their homes or are at serious risk of foreclosure today, compared to just 12 percent of their white counterparts.

- The typical foreclosure costs lenders and investors up to $50,000, borrowers up to $7,000 in administrative costs alone, and local governments up to $34,000 in lost property taxes and associated expenses, before accounting for the indirect costs to the surrounding community.

Foreclosure is often the worst-case scenario for every party involved, since it results in extraordinarily high costs to borrowers, lenders, and investors—not to mention the spillover effects on the surrounding community and the broader economy. And since millions of at-risk mortgages are owned or guaranteed by the federal government, taxpayers are on the hook for billions in foreclosure-related losses.

There are several ways to lower an at-risk borrower’s monthly payments and increase the chance of repayment. If the borrower is current on their payments, they often have the choice to refinance to today’s historically low interest rates, saving an average of $2,600 a year in interest payments.18 If the borrower has fallen behind, the investor can often save money by working out a new deal, usually by extending the loan’s terms, modifying the interest rate, deferring payments, or lowering the amount the borrower actually owes on the loan—so-called principal reduction. Or, if the borrower either can no longer afford the house or does not wish to stay, they can still leave gracefully without going through a foreclosure, either by handing the home back to the lender (known as a deed-in-lieu-of-foreclosure) or negotiating a short sale with the mortgage investor.

In a well-functioning market, the lender or mortgage investor responsible for the loan considers a range of options when deciding which intervention is best for the specific borrower, and negotiates a deal that minimizes losses and keeps families in their homes when possible. But we’re not in a well-functioning market. Recent experience has shown that mortgage servicers—the companies in charge of collecting timely mortgage payments on behalf of the investor—are often unwilling or unable to work with struggling homeowners, even when those homeowners want to work with them. The result is unnecessary foreclosures which harm the borrower, the investor, surrounding homeowners, and the larger economy.

CAP Policy Recommendation

Streamline refinancing for all borrowers current on their monthly payments and meet minimum underwriting standards (See: John Griffith, “Tossing a Lifeline to Underwater Homeowners” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2012)) and establish clear and fair standards for mortgage servicers dealing with struggling borrowers. (See: Peter Swire and Jordan Eizenga, “The Importance of a Homeowner Bill of Rights” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2012)

2.From the peak of the market in 2006, the total amount of home equity in the United States declined by more than $7 trillion, leaving all homeowners with less wealth and more than 11 million families owing more than their homes are worth. How do you plan to address this pressing problem of “underwater” mortgages?

Fast Facts

- Depending on the source, between 24 percent and 31 percent of homeowners with mortgages are underwater, totaling between $700 billion and $1.2 trillion in “negative equity,” the amount above the value of a home an underwater borrower owes.

- Between 2005 and 2009 the typical Hispanic homeowner saw their home equity decline by 51 percent, roughly two-and-a-half times the decline for black and white borrowers.

- Of the roughly 8 million underwater homeowners that are current on their monthly mortgage payments, more than 40 percent are likely unable to refinance to today’s historically low interest rates simply because they have private loans that are ineligible for certain federal programs.

- Analysis by the Federal Housing Finance Agency found that targeted principal reductions of loans backed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac could save the companies $3.6 billion, mostly from fewer foreclosures. Those savings do not count the boost to the economy from increased consumer spending.

If the housing market is weighing down our economic recovery, negative equity is the anchor at the end of the chain. Underwater borrowers are at significantly higher risk of foreclosure than borrowers with equity in their homes, in part because if something unexpected happens—such as a death in the family, divorce, disability, or temporary bout of unemployment—the borrower has no cushion to fall back on.24 These borrowers typically have trouble refinancing to today’s historically low rates simply because they don’t have equity and they often have trouble selling their homes—say, to move for a new job opportunity—because the bank has to agree to take a loss through a short sale.

Then there are the broader economic impacts of negative equity. Underwater mortgages constrain lending beyond the housing market, as home equity is a critical source of capital or collateral for small businesses,25 college students,26 and elderly adults. Homeowners with little or no equity are often reluctant to invest in renovations and home improvements, stifling demand for home-related products from window curtains to washing machines. Borrowers digging their way out of mortgage debt spend less in stores, making businesses leery of investment. For these and other reasons, analysts have observed that the recovery is weakest in places where mortgage debt is the highest.

CAP Policy Recommendation

Encourage targeted principal reductions at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac using “shared appreciation,” where the entities agree to write off some of the outstanding balance in exchange for a portion of any future price appreciation on the home. (See: John Griffith and Jordan Eizenga, “Sharing the Pain and Gain in the Mortgage Market” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2012)

3.For the communities already hit hard by the foreclosure crisis, how do you plan to revitalize neighborhoods and stabilize local housing markets?

Fast Facts

- On average, a foreclosure reduces the value of a house by 27 percent and reduces the value of all other houses in the neighborhood by 1 percent.

- In 2009 alone analysts estimated that 2.4 million foreclosures caused property values to drop for 69.5 million neighboring homes, totaling more than half a trillion dollars in “spillover” home devaluation. That’s an average devaluation of $7,200 per neighboring home that year.

- Nearly half of all foreclosed properties are located in just 10 percent of the nation’s census tracts. One-quarter of foreclosures or at-risk loans are in low-income neighborhoods, while 20 percent are in minority neighborhoods.

While foreclosures have skyrocketed nationwide, some areas are particularly hard hit, from impoverished urban neighborhoods to ghosttown exurbs. Each foreclosure drives the surrounding property values down further, leading to a downward spiral of more foreclosures and additional value decline. Multiple foreclosures cost states and localities enormous sums of money in lost tax revenue, prompting deep cuts to critical public services.

At the same time, vacant or inadequately maintained homes attract crime, arson, and squatters, which increases costs for fire, police, and other services. As people leave the neighborhoods, local businesses are forced to shutter their doors, leading to yet another spiral of departure, foreclosures, and business failures. Health and safety can be impacted by uncollected garbage, dilapidated homes, and abandoned pets; for example, in states such as California and Florida, untended swimming pools have become a breeding ground for disease-carrying mosquitos.

In some blighted neighborhoods the overhang of foreclosed homes—many of which are owned by the government through Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Housing Administration35—gluts the for-sale market, keeping home prices low. In others, foreclosed homes are largely being purchased by investors and rented out, which can provide a useful source of affordable housing but may also significantly change the nature of the neighborhood without additional investment and attention.

CAP Policy Recommendation

Rehabilitate certain government-owned foreclosed properties and convert them to affordable, energy-efficient rentals through “Rehab-to-Rent.” (See: Alon Cohen, Jordan Eizenga, John Griffith, Bracken Hendricks, and Adam James, “Rehab-to-Rent Can Help Hard-Hit Communities and Our Economy” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2012))

4.The need for affordable rental housing continues to rise, with 5 million more low-income renters than there are affordable rental units. At a time of fiscal austerity, how do you plan to meet this unmet need?

Fast Facts

- The total number of “severely cost-burdened households” (those paying more than half their income on housing) nearly doubled over the past decade. The affordability crunch has disproportionally hit communities of color: Today 27 percent of black families and 25 percent of Hispanic families are severely burdened, compared to just 15 percent of white families.

- Twenty-seven percent of renters are severely cost-burdened, which is more than twice the rate for homeowners. Only about a quarter of cost-burdened renters receive federal assistance.

- Today there are 5.1 million more low-income renters than there are affordable rental units—more than double the shortfall observed in 2001. Of the affordable units that are available, more than 40 percent are occupied by higher-income renters.

- Last year’s budget cuts hit affordable housing programs especially hard, including a 38 percent cut to the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s HOME Investment Partnerships program and a 12 percent cut to the Community Development Block Grant program. Total federal funding for public housing decreased by more than 20 percent between 2010 and 2012 despite approximately $26 billion in unmet repair and renovation needs in the nation’s aging public housing stock.

Nearly 100 million Americans—roughly one-third of the U.S. population—live in rental housing. Renters on average earn less than homeowners yet spend more on housing each month as a percentage of income45 and they face an even more expensive future. Rental vacancies hit a 10-year low in 2011 and rents increased last year in 24 of the 25 markets tracked by realty firm Trulia. The foreclosure crisis is partly to blame for these increases: Families often have to wait up to seven years following a foreclosure to obtain financing to purchase another home, during which they have no choice but to rent.

Wages have not kept up with this increase in rents, leaving one in four renters today paying more than half of their monthly income on rent.48 Meanwhile, as the number of low-income renters grew by 2.2 million over the last decade, the number of adequate and affordable rental units actually decreased. As needs skyrocketed, lawmakers actually cut federal support to key affordable housing programs such as public housing, the HOME Investment Partnerships program, and the Community Development Block Grant program.

Unaffordable rents are depressing demand for goods and services. Lower-income families in unaffordable housing units spend 50 percent less on clothes and health care, 40 percent less on food, and 30 percent less on insurance and pensions compared to families in affordable units, according to Harvard’s Joint Center on Housing Studies.

CAP Policy Recommendation

Capitalize the Housing Trust Fund, ramp up funding for Low Income Housing Tax Credits, guarantee certain debt issued by Community Development Financial Institutions, and establish a stable, liquid, and responsible market for multifamily housing finance. (See: Mortgage Finance Working Group’s Multifamily Subcommittee, “A Responsible Market for Rental Housing Finance” (Sponsored by the Center for American Progress, 2010)

5.The U.S. homeownership rate has dropped significantly in recent years as a result of foreclosures and tightened credit standards. Do you think it is important for more Americans to be able to buy homes? If so, what role do you think the federal government should play in achieving that goal?

Fast Facts

- The U.S. homeownership rate fell from 69.2 percent in 2004 to 65.4 percent in the first quarter of 2012—the lowest level in 15 years. Still, nearly three-quarters of renters and homeowners surveyed by Fannie Mae believe that now is a good time to buy a home.

- Today 48 percent households of color are homeowners, the lowest level since 2000. By comparison, 74 percent of white households own their home.

- Lenders originated about $400 billion in home purchase loans in 2011, compared to a peak of $1.5 trillion in 2005.

- Credit standards have gotten much tighter since the crisis began. In 2007 the average Fannie Mae-backed loan covered 75 percent of the home’s value (meaning the borrower of covered the other 25 percent through a down-payments and mortgage insurance) and went to a household with a credit score of 716. Last year’s average loan covered just 69 percent of the home’s value, and the average borrower had a credit score of 762.

Homeownership remains a key part of the American Dream. Owning a home provides economic stability for middle-class families, builds wealth that can be transferred across generations, and encourages residents to maintain their properties and invest in their communities.

But in recent years it has become increasingly difficult for the average American family to become a homeowner. In response to the too-loose credit standards of the housing bubble, many mortgage lenders have overcorrected by extending credit to only the safest possible borrowers. Meanwhile, government regulators are writing rules that will likely determine who gets a mortgage for decades to come. There is also concern that excessively high down-payment requirements could lock many creditworthy families out of the market completely.

In designing the mortgage market of the future, policymakers must consider the right balance between reining in excessive risks and promoting reasonable access to mortgage credit, as well as the appropriate levels of homeownership versus rentership in our country.

CAP Policy Recommendation

Establish a new system of housing finance in the United States that reins in excessive risk-taking, supplies mortgage capital in every community even in times of economic duress, and preserves long-term, reasonably priced products like the 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage. (See: “A Responsible Market for Housing Finance,” 2011)

6.What do you plan to do with the government-backed mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac? If you plan to eliminate them, what will you replace them with and how will you transition to a new system without causing undue harm to the fragile housing market?

Fast Facts

- Since being placed under government control in September 2008, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have required roughly $150 billion in taxpayer support. Analysts estimate it could take as long as 15 years for the companies to pay that money back.

- More than 95 percent of new home loans made last year were backed by the federal government through Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Housing Administration. At the height of the bubble in 2006, these entities backed less than 35 percent of loan originations.

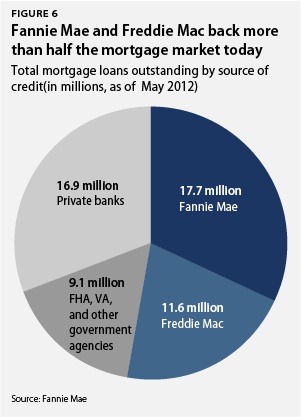

- Fannie and Freddie own or guarantee a combined $5 trillion in mortgage assets, more than half of all outstanding home loans in the United States.

- The financial situations at both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have improved in recent months. Fannie has reported profits in its past two quarters, while Freddie in August reported its best quarterly earnings in 10 years.

For decades, the government-controlled mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have played a crucial role in the U.S. mortgage finance system as a “secondary mortgage market.” To help capital flow into the market, Fannie and Freddie purchase home loans made by private firms, provided they meet strict size, credit, and underwriting standards. They then guarantee timely payment of principal and interest on those loans, either as investments held in a portfolio or through mortgage-backed securities issued to outside investors. Since mortgage lenders no longer have to hold these loans on their balance sheets, they have capital available to make more loans to creditworthy borrowers.

In September 2008 Fannie and Freddie suffered massive losses as the housing market crumbled around them, forcing the federal government to take control of the companies through a legal process called conservatorship. Since then the government has backed nearly all home loans made in the United States, as investors have shown little appetite for purchasing mortgages without a government guarantee.

Just about everyone agrees that the current level of government support is unsustainable in the long run and private investors will eventually have to assume more risk in the mortgage market. But policymakers have yet to grapple with other important questions: What sort of presence should the federal government have in the housing market of the future? And when is the right time to start moving toward this new system of U.S. housing finance?

The answers to both questions will have major implications for the availability and affordability of mortgage finance—and thus access to homeownership—for millions of American families. For example, many experts believe that the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage, now a pillar of the U.S. housing market, would largely disappear without a government guarantee.

CAP Policy Recommendation

Gradually wind down Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and replace them with a new system capitalized by private capital, with an explicit government backstop against catastrophic risk on certain well-regulated mortgage products. (See: John Griffith, “The $5 Trillion Question: What Should We Do with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac?” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2012))

7.At the peak of the housing bubble, more than half of subprime loans went to borrowers who could have qualified for conventional, safe mortgages, many of whom were borrowers of color. How do you plan to prevent racial and ethnic discrimination in the U.S. housing market and promote access to affordable, sustainable mortgages to all capable borrowers?

Fast Facts

- Subprime loans jumped from 9 percent of total mortgage originations in 1996 to 20 percent in 2006.62 That year an astonishing 61 percent of subprime loans went to borrowers with credit scores high enough to qualify for conventional loans with far better terms.

- During the housing bubble, African American or Latino borrowers with good credit were three times more likely than their white counterparts to receive a risky subprime loan, and more than three times more likely to receive a high-interest loan.

- Thirty-eight percent of African American applicants for conventional home purchase loans were turned down in 2010, compared to 23 percent in 2004. The denial rate for white applicants climbed from 12 percent to 15 percent over that period.

- The Federal Housing Administration, a government-run mortgage insurer, provided access to credit for 60 percent of all African American and Hispanic homebuyers in 2010, compared to less than 10 percent in 2006.

During the height of the housing bubble, loan originators backed by Wall Street capital often steered borrowers toward risky subprime loans, even when they qualified for better loans. These predatory products, such as adjustable-rate mortgages with pricing gimmicks, were designed to fail, both encouraging borrowers to borrow far more than they could manage and requiring the borrower to refinance every couple years. Not surprisingly, these loans defaulted at significantly higher rates than conventional mortgages.67 Borrowers of color were disproportionately targeted, as black and Hispanic borrowers were three times more likely to be steered to subprime loans than their white counterparts.

Regulators are finalizing new rules for the entire mortgage finance system, including bans on predatory lending by loan originators. In the meantime, private lenders have drastically scaled back lending activity by tightening underwriting standards for mortgage loans, with serious consequences for communities of color. For example, homeownership rates have declined by about 4.3 percentage points for black households since their peak, nearly double the decline for white households.

Racial disparity and discrimination in mortgage lending is nothing new, and efforts from federal and state governments during the 1990s and early 2000s made slow but sure headway in reducing the racial homeownership gap. But the recent crisis has erased most of that progress.

CAP Policy Recommendation

Vigorously implement key mortgage-market reforms laid out in the Dodd-Frank Act, including a requirement that lenders must ensure a borrower’s ability to pay back a home loan at the time of origination. Also, make fair and equitable access to affordable mortgage credit a key pillar of any future system of housing finance. (See: “A Responsible Market for Housing Finance,” 2011)

A moment of urgency

In recent months, several analysts have predicted that the housing market has finally bottomed out and that we’re now in the beginning stages of a housing recovery. We hope that’s true.

But even if the worst days are indeed behind us, the housing crisis is far from over. Millions of struggling families still risk losing their homes. Tens of millions of renters still face unmanageable housing costs. Countless more creditworthy families still dream of owning a home but can’t get approved for a mortgage.

Each of these problems has ripples beyond the housing market. Whether it’s a homeowner drowning in mortgage debt, a low-income family paying half their income on rent, or a potential homebuyer being closed out of the market, the crisis continues to stifle demand for goods and services, impeding efforts to grow and create jobs.

Our presidential hopefuls cannot stay silent on this critical issue. After months of arguing about tax reform, budget cuts, health care, outsourcing, and private equity, it’s time for housing to get its time in the spotlight.

John Griffith is a Policy Analyst with the Housing team at the Center for American Progress. Julia Gordon is the Center’s Director of Housing Finance and Policy. David Sanchez is a Special Assistant with the Center’s Economic Policy team.

Download this issue brief (pdf)

Read this issue brief on your browser (Scribd)