This issue brief contains a correction.

As postsecondary education or training has become more essential for economic success, policymakers have begun to give apprenticeship a closer look. At the federal level, President Barack Obama has dedicated $175 million to an American Apprenticeship grant initiative that will help 46 public-private partnerships create more opportunities for workers and employers to participate in apprenticeship. Congress recently dedicated new funding to grow apprenticeships as well. Importantly, this new federal action follows leadership by states to spur innovation in apprenticeship and revitalize this effective, but underused worker training strategy.

It has become harder than ever for workers without an education beyond high school to secure a foothold in the middle class. Increasingly, employers require workers to have some form of postsecondary education to get in the door, and many require workers to upgrade their skills over time. According to one study, nearly two-thirds of all jobs will require some form of postsecondary education or training by 2020. As a result, more Americans are going to college or seeking some other type of educational credential, such as an occupational certificate or an industry-recognized credential awarded through an apprenticeship or other worker training program.

Apprenticeship is a proven worker training strategy that combines on-the-job training with classroom instruction, but is notably underused in the United States. For workers, apprenticeship means a real job that leads to a credential that is valued in the labor market. Apprentices are paid for their time spent on the job, accumulate little to no student debt, and are generally retained once they have successfully completed their programs.* Apprenticeship completers also make middle-class wages; according to the U.S. Department of Labor, which administers the Registered Apprenticeship system, the average wage for an individual who has completed an apprenticeship is $50,000. Over a lifetime, this can add up to approximately $300,000 more in wages and benefits compared to their peers. For employers, apprenticeship is an effective and cost-efficient strategy to build their current and future workforce. In addition to lower recruitment and relocation costs, it can enable employers to develop strong talent pipelines. States, often regarded as so-called laboratories of democracy for their ability to experiment with innovative policies, have been leading the way in developing strategies to prepare more workers for employment through apprenticeship. This brief profiles states that have found innovative policy solutions to develop the human capital of workers through apprenticeship. The strategies they have deployed occur at all different levels of leadership, and with different levels of financial investment.

Specifically, this brief highlights four state strategies to grow apprenticeships:

- Directing state funds to establish new and grow existing programs

- Convening partnerships to develop high-quality, effective programs that address the workforce needs of the state

- Building a talent pipeline through pre-apprenticeship and youth apprenticeship

- Establishing a comprehensive plan to integrate apprenticeship as part of a state’s broader workforce strategy

These efforts can serve as a roadmap for other states seeking to address increasing employer demand for skilled workers and worker demand for access to good jobs, as well as for the federal government, as the Obama administration and Congress continue to consider what other policy changes are needed to establish a more comprehensive system of apprenticeship in the United States.

Administration of the Registered Apprenticeship System in the United States

The U.S. Department of Labor Office of Apprenticeship administers the Registered Apprenticeship system. As noted in an Center for American Progress report, “Training for Success,” the system consists of a national office, six regional offices, and local offices in each state. The Office of Apprenticeship directly administers the program in 25 states, and delegates some operational authority to state apprenticeship agencies in 25 states and the District of Columbia.

The Office of Apprenticeship is responsible for:

- Program approval and standards

- Program and apprentice registration

- Worker safety and health

- Issuing certificates of completion

- Ensuring that programs offer high-quality training

- Promoting apprenticeships to employers

State apprenticeship agencies devote most of their resources to approving for new occupations for apprenticeship and on program and apprentice registration with the federal Department of Labor.

Directing state funds for apprenticeship

Direct state investment in apprenticeship can be an important incentive to encourage employer participation. Apprenticeship is primarily financed by employers, who pay wages to apprentices and typically finance the classroom portion of apprenticeship as well. Studies have found that employers get a significant return on that investment. According to one study, employers get an average of $1.47 back for every $1 invested in apprenticeship. Moreover, state funding for apprenticeship can be a powerful multiplier. When a state invests in apprenticeship, more companies invest in their workforce. Activities in Iowa, Connecticut, and California demonstrate how state funding can be used to further develop existing policies and promote new private investments in worker training.

Iowa

Iowa has become a leader in developing and supporting strategies to increase Registered Apprenticeship. Thanks to strong leadership by the federal Office of Apprenticeship, which oversees Registered Apprenticeship in the state, Iowa has registered more new programs than nearly every other state over the past few years. Building on these efforts, Iowa enacted the Apprenticeship and Training Act in 2014. Initially proposed by Gov. Terry Branstad (R) in his 2014 Condition of the State address and subsequent budget proposal, the act established an apprenticeship program training fund and set annual appropriations at $3 million, tripling the amount of state funding available to support apprenticeship programs. The Iowa Economic Development Authority is responsible for overseeing the funding. This initiative complements other efforts to attract new businesses to the state, which recently became home to large data centers for Facebook, Microsoft, and Google.

The apprenticeship training program funds will be used to support grants to Registered Apprenticeship program sponsors—which are typically employers, labor-management partnerships, or industry associations—to subsidize the cost of apprenticeship programs. Such costs include related classroom instruction, purchasing equipment for the apprenticeship program, and establishing new locations to expand apprenticeship training. As of 2015, 67 sponsors had submitted applications to receive grant funds.

Connecticut

In July 2015, Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy (D) launched a new two-year, $7.8 million Manufacturing Innovation Fund Apprenticeship program. The program was established as part of the Connecticut Department of Economic and Community Development’s $30 million Manufacturing Innovation Fund, which is designed to invigorate the state’s manufacturing sector and will be administered by the Connecticut Department of Labor. The program will offer grants to manufacturing employers and providers of related classroom instruction to support apprenticeship training. The funds may be spent on wage subsidies, related instruction at six community colleges, or credentialing costs associated with competency- or performance-based programs.

California

California has long funded apprenticeship. Since 1970, the state has provided annual appropriations to support related classroom instruction—otherwise known as Montoya Funds. The California Community College Chancellor’s Office, or CCCCO, is responsible for disbursing the funding to community colleges across the state that partner with apprenticeship sponsors to provide related instruction. In the 2013-2014 budget, California appropriated $22 million in Montoya Funds. The 2015-2016 budget increased funding for the program by $29.1 million, including $14.1 million for related instruction. The remaining $15 million will go towards facilitating pre-apprenticeship, innovative apprenticeship programs, an Apprenticeship Accelerator program, and technical assistance.

In addition, the California Employment Training Panel, which supports employer-provided training, has invested more than $30 million in the past three years in a new Apprenticeship Training Pilot program. The pilot provides funding to apprenticeship program sponsors to supplement the limited Montoya Funds. The ETP expects to invest several million dollars annually over the next five years to support new, nontraditional apprenticeship programs.

This apprenticeship is an invaluable opportunity for me to gain skills and explore new interests. The classes especially, allow me to discover new interests and better my trade. They are professional development opportunities in addition to my daily training at work. This program is an investment for a long career. I believe apprenticeship classes in the trades is very similar to attending college; it’s a set number of years that allow students, like myself, to gain job skills necessary for today’s workforce.

— Lynna Vong, a Second Period Carpenter Apprentice in San Francisco

Convening partnerships for success: Minnesota

Partnership is often a crucial ingredient in developing strong workforce development programs, including apprenticeships. Apprenticeship systems in countries such as England, Germany, and Switzerland thrive in part because they leverage resources and expertise from a range of stakeholders representing government, labor, employers, education, and others. Minnesota recently adopted an approach to expanding apprenticeship modeled after the renowned German dual training system, which brings together partners across sectors to establish seamless pipelines from education to a job for young people. Minnesota’s PIPELINE—or Private Investment, Public Education, Labor, and Industry Experience—project seeks to provide pathways to work for young people and adults through dual training and Registered Apprenticeship.

Apprenticeship is a form of dual training, albeit more formalized. For example, registered apprenticeship must be registered with the U.S. Department of Labor, adhere to minimum standards concerning time spent in the classroom and on-the-job and wages, and culminate in a nationally recognized completion certificate—whereas dual training does not.

The state legislature passed PIPELINE in 2014. It is administered by the Minnesota Department of Labor and Industry, or DLI, in partnership with the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development and Minnesota State Colleges and Universities. The legislation called for state agencies to convene various stakeholders to define competency standards for occupations in advanced manufacturing, agriculture, health care services and information technology. DLI and the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development convened four principal industry councils that included representatives from higher education, industry, labor and employers to explore an industry approach to developing and delivering dual-training and Registered Apprenticeship programs. These councils had between 25 and 50 participants, the majority of whom were major employers in the state.

The PIPELINE Industry Councils also identified occupations in each industry that were well suited for apprenticeship. Competency councils made up of occupation experts as well as related instruction providers such as community colleges began developing industry validated occupational competencies. While many of these skills were already taught at various institutions across the state, some courses had to be created from scratch. Competencies are reviewed and amended annually depending on the industry’s needs.

More than 400 recognized industry experts, representative employers, higher education institutions, and labor representatives currently participate in ongoing industry council discussions about the development of dual training and Registered Apprenticeship programs in these industries. DLI continues to engage with council representatives periodically throughout the year.

Spurred by the program’s success, the state legislature voted in June 2015 to continue the PIPELINE project, and to establish a new grant program administered by the Minnesota Office of Higher Education to support employer-provided training in occupations for which the PIPELINE project has identified a competency standard. Grants are awarded directly to employers that have an agreement with a training institution or program to provide the training.

Building the pipeline through youth apprenticeship

A growing number of states have established programs to develop youth apprenticeships, which provide pathways into apprenticeship for young people. These programs are important tools to equip both young people with the tools they need to succeed in apprenticeship, or in other employment.

Youth apprenticeships, which are geared toward those enrolled in high school, expose students to work and ease the transition into college or career. They may even lead to an apprenticeship right out of high school. Youth apprenticeship programs provide structured work-based learning opportunities that involve elements of an apprenticeship, such as classroom learning and on-the-job experience.

Pre-apprenticeship

Like youth apprenticeship, pre-apprenticeships recruit and train workers to succeed in apprenticeship. Pre-apprenticeship programs are workforce development programs that teach workers the skills they need to qualify for apprenticeship, and activities range from job-readiness, to contextualized literacy and numeracy instruction, case management, and placement. These programs are open to workers of all ages, and tend to focus on low-income adults and populations that are underrepresented in apprenticeship programs. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, “women and minorities continue to face substantial barriers to entry into and, for some groups, completion of registered apprenticeships, despite their availability in industry sectors that include apprenticeable occupations.” Pre-apprenticeships play an important role in improving underrepresented groups’ access to apprenticeships, and ensuring better completion rates for women and minority apprentices.

Kentucky

The Tech Ready Apprentices for Careers in Kentucky, or TRACK, program, is a youth pre-apprenticeship program designed to prepare young people for college or a career after high school. The TRACK program was developed by the state Office of Career and Technical Education and the Kentucky Labor Cabinet—working in partnership with employers, trade associations, and unions—and is built on existing programs at career and technical education centers across the state that were then customized to meet industry needs. The program initially began in 2013 as an advanced manufacturing competency-based pilot program in 13 high schools. After some initial success, Kentucky has established programs in carpentry, electrical technology, and welding.

Students who complete the TRACK program earn an industry certification and a state-recognized portable credential. If they subsequently enter a Registered Apprenticeship program, they earn credit for prior learning that occurred on the job in their pre-apprenticeship—which puts them closer to completing a Registered Apprenticeship program. After the first year of the program, all of the participating students moved into full-time apprenticeships with their employer sponsors. In order to protect employers from potential liability associated with hiring students younger than age 18, the Kentucky Department of Education has established the Youth Employment Solutions program, which partners with a staffing agency that acts as the employer of youth apprentices and alleviates the risk to employers who provide on-the-job training.

Wisconsin

Wisconsin boasts one of the oldest youth apprenticeship programs in the country. The program, established in 1991 as part of a state-led school-to-work initiative, provides students with skills specific to an occupation, as well as more general job-readiness skills and exposure to the world of work. The program is overseen by the state Department of Workforce Development, which is responsible for establishing program standards; funding youth apprenticeship consortia in the state; working with industry to develop youth apprenticeship program areas; approving statewide program curricula; providing technical assistance and program monitoring; and issuing Certificates of Occupational Proficiency to youth who successfully complete the program. Funding is allocated on a competitive, annual basis to local partnerships that mutually implement and coordinate the program through a local consortium steering committee. Local partnerships are defined as one or more school districts and other partners.

The program offers one- to two-year apprenticeships to 2,500 high school juniors and seniors. Students must complete 450 to 900 hours of work-based learning, and two to four semesters of classroom instruction. Students are paid for their work on the job, and, upon completion, they receive a certificate of occupational proficiency, and potentially some college credit as well. Recently, the Wisconsin Bureau of Apprenticeship Standards began to integrate the youth program with the state’s Registered Apprenticeship program, which will help ease the transition for youth into Registered Apprenticeship after high school graduation.

World Wide Sign Systems and Bonduel High School

In October 2015, World Wide Sign Systems, Inc., partnered with Bonduel High School to pair one apprentice-student with an employee-mentor who taught him custom fabrication. World Wide reports that, in addition to building occupational skills, the first youth apprentice also learned the importance of good attendance, listening, following directions, and teamwork. Furthermore, he received an educational experience beyond what the typical classroom setting offered.

Following the positive experience with the company’s first apprentice, World Wide took on a second apprentice as an office clerk. That apprentice will learn general office duties and, eventually, finance and accounting related skills.

In a letter to the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development, World Wide said:

The YA [or Youth Apprenticeship] program allows our staff to act as mentors, trainers, positive role models and hopefully create long term interest in manufacturing as well as offering something back to our local community. As a company we get back dedicated and enthusiastic employees who fill vital roles in our staffing. I see us expanding the program in Bonduel as well as including our Shawano plant.

Establishing a comprehensive plan: South Carolina

Often used as a model for states who are interested in developing or expanding apprenticeship, South Carolina’s Apprenticeship Carolina program offers comprehensive assistance to employer sponsors—including an employer tax credit, hands-on administrative assistance from Apprenticeship Consultants, and access to the state’s technical college system. Such assistance encourages employers to agree to sponsor apprentices.

Employer tax credits

Since the program launched in 2007, South Carolina has offered employers who sponsor apprentices a modest tax credit of $1,000 per apprentice. This tax credit can last for up to four years and helps subsidize employer investments.

Apprenticeship Consultants

In addition to the employer tax credit, South Carolina offers Apprenticeship Consultants to employers at no cost. These consultants are often the first point of contact for employers, and guide them through the process of starting a new apprenticeship program.

Consultants meet with businesses and discuss employment needs and skills gaps. They help facilitate the process of registering an apprenticeship by, for example, finding existing registered apprenticeship models that may fit the employer’s needs and seeing employers through the registered apprenticeship process with the U.S. Department of Labor. Consultants also help on the back-end by maintaining a clear line of communication with sponsors throughout the apprenticeship. Finally, they conduct annual performance evaluations of the apprenticeship.

South Carolina currently has five apprenticeship consultants, each assigned to specific counties. The state recently added the fifth consultant to specifically advise companies that want to start a youth apprenticeship. This consultant works to connect companies looking to build talent pipelines early with high school tech centers throughout the state.

Consultants in South Carolina have been effective at engaging employers and highlighting the value of apprenticeship. By enabling businesses to move seamlessly through the registration process, while simultaneously ensuring that those models are achieving a high level of quality, this consulting function has proven its worth in engaging employers and creating new opportunities for workers to participate in apprenticeship.

South Carolina Tech

Apprenticeship Carolina is embedded within the South Carolina Technical College system. This structure emerged largely from a recommendation in a 2003 report that said, “the best central organization for promoting apprenticeship programs in the state would be the SC Technical College System.” Following the 2005 creation of a Registered Apprenticeship Task Force as wells as the allocation of $1 million in state funding to the South Carolina Technical College System, Apprenticeship Carolina was born. Today, along with readySC, an intermediary that works with new business entrants that are either expanding or are opening new firms in South Carolina, Apprenticeship Carolina operates as an affiliate of the Division of Economic Development within the technical college system.

South Carolina apprentices can receive related instruction from either a noncredit customized training program, or an associate degree or otherwise for-credit program depending on the needs of the company. The coordination between Apprenticeship Carolina and SC Technical School System helps provide this training in a manner that is rigorous and efficient. More importantly, the dynamic allows employers to coordinate closely with colleges in order to design curricula that best serve the company’s workforce needs.

Today, the state’s technical college system provides support to a variety of industries including advanced manufacturing, healthcare, information technology, and transportation. As Brad Neese, formerly of Apprenticeship Carolina noted, “When companies are looking for talent, they often recruit directly from one (or more) of our colleges.” The joint efforts of the South Carolina Technical College System and readySC have been integral to the apprenticeship growth in South Carolina. To date, Apprenticeship Carolina has served more than 14,000 apprentices. In addition, Apprenticeship Carolina has seen tremendous growth in the number of employer sponsors. Since the program launched, the number of employers offering apprenticeships in South Carolina has grown by more than 750 percent.

What states can do

Going forward, other states interested in developing their own apprenticeship policies can look to these states for inspiration or test new strategies using their own available resources and expertise. No matter what path a state chooses to take, these examples can serve as a helpful guide.

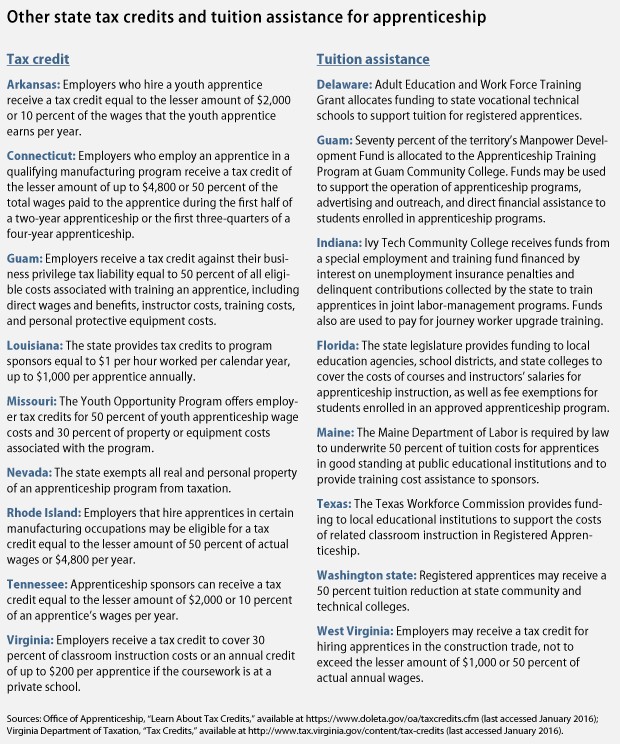

For example, states can consider providing financial support for apprenticeship programs, either by following the California model of subsidizing the related instruction portion of apprenticeship, or by providing other financial assistance to employers through tax credits like South Carolina or grants like Iowa. As these examples show, public investments can affect employer willingness to participate in apprenticeship.

Importantly, states should also ensure that industry is engaged at every step in the process, and recognize that it can play a crucial role as a convener. States can bring business together with workforce development, economic development, and education stakeholders to build successful programs. The first step Minnesota took in developing a program to rival the German model was to organize stakeholders so that the employers’ voices were at the center. Building upon that foundation, the state was able to expand the PIPELINE project and establish a grant program that will put the plan those stakeholders developed into action.

States may also consider leveraging existing resources, such as career and technical schools, to support apprenticeship strategies. Wisconsin’s use of the state’s existing infrastructure is an example of an efficient use of resources that are already spread across the state.

Finally, states should look into developing pre-apprenticeship and youth apprenticeships strategies to build pipelines into apprenticeship and careers for youth and underrepresented or low-income workers. These programs are particularly important for making apprenticeship programs more diverse, and able to serve a broad range of workers. Building these talent pipelines will help employers plan for their future employment needs, and can establish a sustainable pathway for workers into good careers.

Through smart policies that address the needs of business and workers, states can build a stronger, more productive, and thriving workforce and help grow the economy.

Angela Hanks is the Associate Director for Workforce Development Policy on the Economic Policy team at the Center for American Progress. Ethan Gurwitz is a Research Associate with the Center’s Economic Policy team.

*Correction, February 17, 2016: This issue brief has been corrected to clarify how employer sponsors employ apprentices after they complete their programs.