The U.S. economy continues to recover at a moderate pace, as it further benefits from smart progressive policy interventions such as small-business support, extended unemployment insurance benefits, and a payroll tax holiday. These have thus far kept the economy from being derailed by the high levels of household debt, weak housing market, and ongoing cuts in state and local government spending. The admittedly tepid but continued expansion of the U.S. economy shows an underlying resilience fueled by targeted economic policies during the past few years.

It is important to keep the duality of a resilient recovery fueled by past policy efforts in mind. New difficulties are now threatening to derail the economy again, just as many past obstacles—such as a weak housing market, high debt levels, and cash-strapped states and localities—are beginning to subside. U.S. exports are slowing due to less overseas growth, and business investments are faltering amid economic uncertainty associated with the fiscal showdown. Policymakers need to quickly resolve the combination of looming tax increases and spending cuts at the start of 2013 in a balanced manner to strengthen economic growth in the short term and lower expected federal deficits over the longer term.

But there is cause for hope. If policymakers can come together to resolve the fiscal showdown in a smart and progressive way—including balancing the need to strengthen the recovery in the short term and reducing federal budget deficits in the long term through a balanced array of pragmatic spending cuts and expanded revenue—there is hope for a strengthening recovery in the months to come, considering the resilience of the recovery so far.

1. Economic growth remains positive. Gross domestic product, or GDP, grew at an annual rate of 2.7 percent in the third quarter of 2012. Government spending grew by 3.5 percent due to a boost in defense spending, but consumption grew by only 1.4 percent, and exports expanded by only 1.1 percent. Business investment actually fell by 2.2 percent in the third quarter of 2012. Slowing growth overseas led to slower export growth in the United States and less domestic consumption, and declining investments are due in part to the economic uncertainty created by the looming fiscal showdown. Policymakers can help strengthen the recovery by quickly removing the fiscal uncertainty in a balanced fashion.

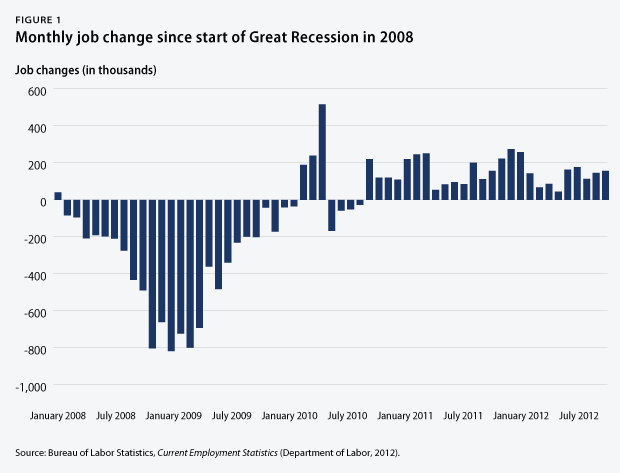

2. The moderate labor market recovery continues in its fourth year. There were 3.3 million more jobs in November 2012 than in June 2009, when the economic recovery officially started. The private sector added 4 million jobs during this period. The difference between the net gain and the private-sector gain is explained by the loss of nearly 600,000 state and local government jobs, as budget cuts reduced the number of teachers, bus drivers, firefighters, and police officers, among others. Job creation is a top policy priority since private-sector job growth is still too weak to quickly overcome other job losses and to rapidly lower the unemployment rate. Once again, removing the uncertainty over the year-end fiscal changes is a key step toward strengthening economic and job growth.

3. Suffering of the unemployed stays high. The unemployment rate stood at 7.7 percent in November 2012, its lowest level since December 2008. But even with the drop in overall unemployment, long-term unemployment, defined as those out of work and looking for a job for more than six months, remained high. In November 2012, 40.1 percent of the unemployed were considered long-term unemployed. The length of unemployment stayed high, averaging 40 weeks for those unemployed during November 2012. Those out of a job for a long time struggle to regain employment because their skills atrophy and re-entry into a new job becomes increasingly harder. The struggles of the long-term unemployed demand policy interventions, most importantly the continuation of extended unemployment insurance benefits.

4. Labor-market pressures fall especially on communities of color, young workers, and those with less education. The African American unemployment rate in November 2012 stayed at 13.2 percent—significantly above its historical average—the Hispanic unemployment rate was 10 percent, and the white unemployment rate was 6.8 percent. Youth unemployment stood at a high 23.5 percent. The unemployment rate for people without a high school diploma stayed high with 12.2 percent, compared to 8.1 percent for those with a high school degree, 6.5 percent for those with some college education, and 3.8 percent for those with a college degree. Population groups that typically have low incomes and little wealth have struggled disproportionately more amid the weak labor market than white workers, older workers, and workers with more education, creating greater need for progressive policy actions to strengthen job creation for everybody.

5. Household incomes continue to drop amid prolonged labor market weaknesses. Median inflation-adjusted household income—half of all households have more and the other half has less—stood at $50,054 in 2011, its lowest level in inflation-adjusted dollars since 1995. It fell by 1.5 percent in 2011—dropping for the fourth year in a row. American families experienced no income gains during the current economic recovery after 2009, exacerbating the losses during the Great Recession.

6. Income inequality is on the rise. Households at the 95th percentile, with incomes of $186,000 in 2011, had incomes that were more than nine times—9.2 times, to be exact—the incomes of households at the 20th percentile, whose incomes were $20,262. This is the largest gap between the top 5 percent and the bottom 20 percent of households since the U.S. Census Bureau began keeping record in 1967.

7. Poverty stays high. The poverty rate fell to 15 percent in 2011, down from 15.1 percent in 2010. The African American poverty rate was 27.6 percent, the Hispanic rate was 25.3 percent, and the white rate was 9.8 percent in 2011. The poverty rate for children under the age of 18 stood at 21.9 percent. More than one-third of African American children (38.8 percent) lived in poverty in 2011, compared to 34.1 percent of Hispanic children and 12.5 percent of white children. The prolonged economic slump, following an exceptionally weak labor market before the crisis, has taken a massive toll on the most vulnerable.

8. Employer-sponsored benefits disappear. The share of people with employer-sponsored health insurance dropped from 59.8 percent in 2007 to 55.1 percent in 2011. The share of private-sector workers who participate in a retirement plan at work fell to 39.2 percent in 2011, down from 42 percent in 2007. Families have less economic security than in the past due to fewer employment-based benefits, requiring more private savings to make up the difference.

9. Family wealth losses linger. Total family wealth is down $9.1 trillion (in 2012 dollars) from March 2007—its last peak—to September 2012. Homeowners on average own only 44.8 percent of their homes, compared to the long-term average of 61 percent before the Great Recession, with the rest of their homes owed to banks. Homeowners are still highly leveraged, slowing consumption growth as households still do not have a lot of collateral. Collateral is needed for banks to loosen their lending standards.

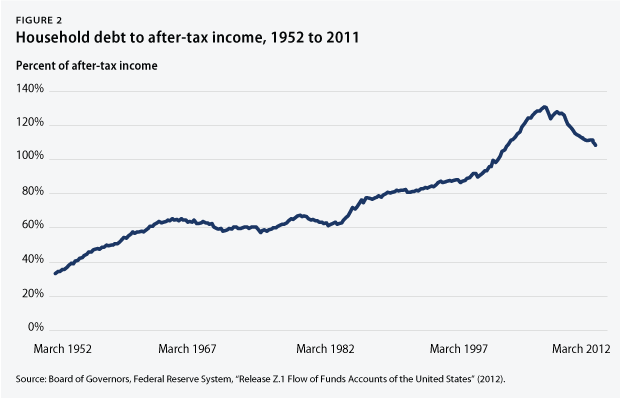

10. Household debt is still high. Household debt equaled 107.7 percent of after-tax income in September 2012, down from a peak of 126 percent in March 2007. The unprecedented fall in debt over the past few years resulted from tight lending standards, falling interest rates, massive foreclosures, and increased household saving. But further deleveraging will likely slow unless incomes rise faster than they have in the past. This high debt could continue to slow economic growth as households focus on saving rather than on spending more.

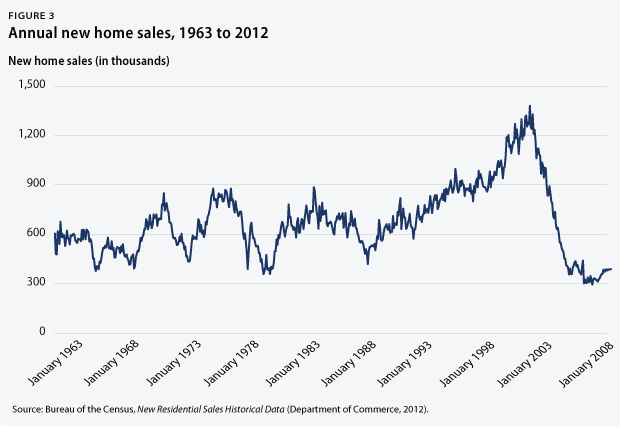

11. The housing market is finally and slowly recovering from historic lows. New home sales amounted to an annual rate of 368,000 in October 2012, a 17.2 percent increase over the 314,000 homes sold in September 2011 but still well below the historical average of 698,000 before the Great Recession. The median new house price in September 2012 was 5.7 percent higher than one year earlier. Existing home sales were up by 10.9 percent in October 2012 from one year earlier, and the median price for existing homes was up by 11.1 percent during this same period. The housing market has a lot of room to grow and to contribute to economic growth because the recovery in the spring of 2012 started from historically low home sales and because the housing market fell throughout most of the recovery.

12. Homeowners’ distress remains high. One in nine mortgages is still delinquent or in foreclosure even though mortgage troubles have gradually eased since March 2010. In the third quarter of 2012, the share of mortgages that were delinquent was 7.4 percent, and the share of mortgages that were in foreclosure was 4.1 percent. Many families delayed and defaulted on mortgage payments amid high unemployment and massive wealth losses. This causes some banks to be nervous about extending new mortgages, further prolonging the economic slump. Policymakers could therefore accelerate economic growth by expediting household deleveraging.

13. Near pre-crisis peak profits are not reflected in investment data. Inflation-adjusted corporate profits were 87.7 percent larger in September 2012 than in June 2009, when the economic recovery started. The after-tax corporate profit rate—profits to total assets—stood at 3.1 percent in September 2012, nearing the last peak after-tax profit rate of 3.2 percent, which occurred prior to the Great Recession. Corporations used their resources for purposes other than investments in plants and equipment. The share of investment out of GDP stayed low, with 10.2 percent in the third quarter of 2012 compared to an average of 10.9 percent during the last business cycle from March 2001 to December 2007.

Christian E. Weller is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress and a professor in the Department of Public Policy and Public Affairs at the University of Massachusetts Boston.