In 2017, President Donald Trump and congressional Republicans enacted the so-called Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA)—a tax plan that was heavily skewed toward wealthy Americans. Ever since, they have been floating rumors about a new tax proposal, which they are calling “Tax Cuts 2.0.” This time, they say, the tax plan will actually be focused on the middle class. No specific plan has been released, but some of the White House’s policy discussions have leaked in the press. True to form, the tax cuts they are considering are hardly focused on the middle class. The rumored elements of Tax Cuts 2.0 include:

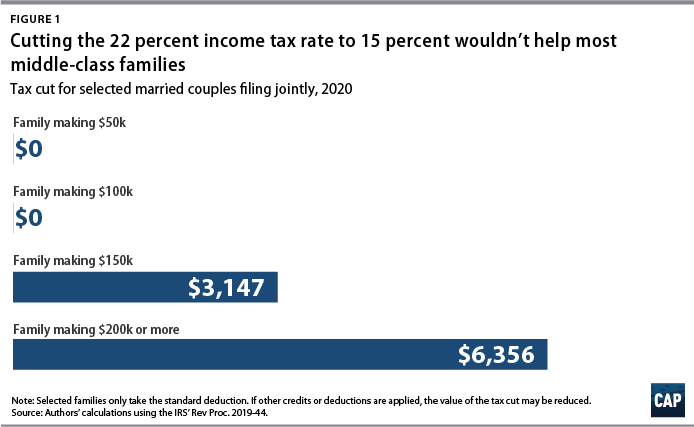

- Lowering the tax rate for the 22 percent bracket to 15 percent. This would make no difference for most middle-class families while benefiting high-income people the most.

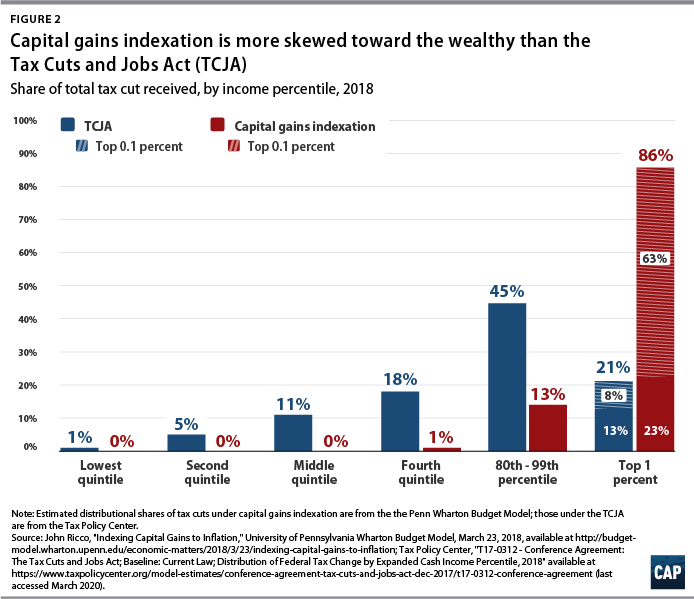

- Indexing capital gains for inflation. This would provide a windfall for wealthy investors.

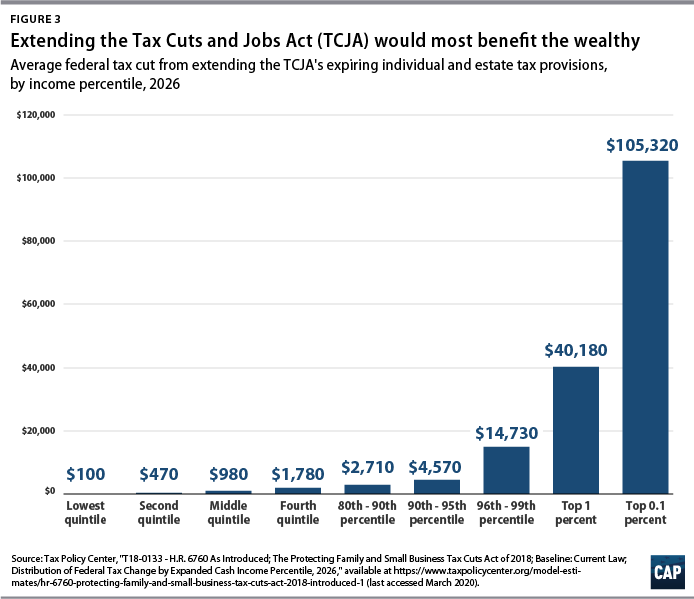

- Extending the individual and estate tax provisions of the TCJA beyond their scheduled expiration date. This would permanently lock in tax cuts that are skewed to the wealthy.

- Creating a new tax-preferred savings vehicle. This would only double down on the tax code’s already very top-heavy investment tax breaks.

- Implementing even more corporate tax cuts. This would overwhelmingly benefit the wealthy, who own most of the corporate stock.

Just like those in the TCJA, these changes and tax cuts would be skewed to high-income taxpayers while draining even more revenue needed for investments in broad-based prosperity.

Cutting the 22 percent income tax rate wouldn’t benefit most middle-class families

One idea floated by both Rep. Kevin Brady (R-TX)—ranking member of the House Ways and Means Committee—and National Economic Council Director Larry Kudlow would lower the 22 percent marginal income tax rate to 15 percent. Some commentators and media outlets dubbed this provision a “middle class” tax cut. Upon closer examination, this is not the case.

To receive any benefit from this rate cut, taxpayers’ incomes need to be high enough to fall in the 22 percent bracket or above. For married couples, the minimum adjusted gross income (AGI) to fall into the 22 percent bracket this year is $105,051.* As most couples in the United States will make less than $105,051 in 2020—or will have deductions that put them below the 22 percent bracket—they wouldn’t benefit at all from the rate reduction. Moreover, because the rate cut would only affect the portion of income that falls within the 22 percent bracket, even those with incomes higher than $105,051 would not see the full benefit unless their incomes place them in higher brackets. For couples, the minimum AGI to be in the next tax bracket is $195,850—three times higher than what the median household earned in 2018.

As a result, most taxpayers would miss out on any benefit. The Tax Policy Center (TPC) estimates that in 2019, 76 percent of households, including all filing statuses, were in tax brackets below the 22 percent bracket. Only the highest-income 7 percent of taxpayers were in the 24 percent bracket or higher—meaning they would get the maximum benefit from the change. If the 22 percent marginal rate were reduced to 15 percent as the Trump administration has discussed, each married couple in the 24 percent tax bracket or higher—a group that, as noted, only includes couples making more than $195,850—would get a tax cut of more than $6,000 in 2020. (see Figure 1) Similarly, each single taxpayer in the 24 percent bracket or above—which only includes singles making more than $97,925—would get a tax cut of more than $3,000.

Altogether, according to CAP calculations using the open-source tax calculator Tax-Brain, nearly two-thirds—64 percent—of the tax cut from this plan would go to taxpayers in the top 10 percent, while the bottom 50 percent wouldn’t see any change at all.

The bottom line: It is important not to assume that reductions in marginal tax rates are middle-class tax cuts, even when it is not the top rates that are being reduced.

Cutting capital gains taxes would almost exclusively benefit the wealthy

Another potential element of the administration’s Tax Cuts 2.0 plan is cutting capital gains by “indexing” them for inflation. The Trump administration has thus far not acted on this idea but has long considered doing so by regulation—though the administration’s legal authority to act without legislation is highly dubious. Indexing capital gains means that taxpayers’ basis in an asset—generally speaking, the cost of acquiring it—would be adjusted for inflation from the time of acquisition. This change would reduce the amount of gain that a taxpayer is required to report when they sell the asset. This particular proposal is estimated to reduce revenues by somewhere between $100 billion and $200 billion over a decade. Because the majority of capital assets are owned by the wealthy, more than 80 percent of the benefit would go to just the top 1 percent of taxpayers, making this proposal even more skewed to the wealthy than the TCJA.

Capital gains already receive preferential treatment under the current tax system. Gains are only subject to taxes when realized—or when assets are sold—and because of the stepped-up basis loophole, they can go completely untaxed when passed on to heirs. Finally, if the gains are eventually taxed, they face lower rates than ordinary income. The indexation proposal would not benefit the vast majority of middle-class taxpayers, whose assets are overwhelmingly in the form of homes or tax-qualified retirement accounts that are already not subject to capital gains taxes. For couples, the first $500,000 of gains on a home, and $250,000 for singles, is exempted from taxation. Furthermore, most taxpayers are in the 0 percent capital gains tax bracket.

Tax Cuts 2.0 would likely double down on the failures of the TCJA

The Tax Cuts 2.0 plan is also likely to lock in the TCJA’s regressive tax cuts by making permanent the individual income and estate tax provisions, which are currently scheduled to expire in 2026. President Trump proposed to make these tax cuts permanent in his recent annual budget, at a cost of $1.4 trillion over 10 years. The then-Republican-controlled House passed a similar proposal in 2018, but it was not enacted. The measure would have given the top 0.1 percent a tax cut of $105,000—more than 100 times larger than the cut for middle-income households and more than 1,000 times greater than the cut for the bottom 20 percent, according to the TPC.

More investment tax breaks won’t help the middle class save more

The White House has also floated the idea of creating a new tax-free investment account as part of Tax Cuts 2.0. The plan could be similar to a congressional Republican proposal for universal savings accounts. The ostensible goal would be to increase savings for working- and middle-class Americans, but this idea misses the mark. The reason that most middle- and working-class Americans do not save more is not that more individual tax incentives are needed, but rather that they lack the disposable income to set more money aside. There already exist several tax-favored savings vehicles, such as 401(k)s, individual retirement accounts, 529 college savings plans, and health savings accounts—but only a small fraction of Americans max them out. The universal savings account proposal would provide the largest benefits to the wealthiest households, who are most able to put money in a tax-favored account, unless maxed out, and who are in higher tax brackets. And studies have also shown that tax incentives such as universal savings accounts are likely to subsidize saving that was already going to occur.

This proposal would drain federal revenues by around $8.6 billion over the first 10 years, and costs would be likely to grow substantially beyond that window as wealthy taxpayers shift more of their investments into the tax-free accounts. All told, this change would likely create another tax shelter for the wealthy and do little for middle-class families.

Even more corporate tax cuts

Undeterred by the failures of the 2017 tax law, the Trump administration is eyeing even more tax cuts for corporations. On February 28, acting White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney said that if President Trump is reelected, he would seek to cut the corporate rate by an additional percentage point, from 21 percent to 20 percent—which would cost about $100 billion over 10 years. The beneficiaries would be the wealthy people—including foreign investors—who own the bulk of corporate stock. If the first two years of the TCJA have taught anything, it is that the bold predictions of investment booms and other benefits flowing down from corporate tax cuts cannot be trusted.

Conclusion

With the TCJA widely and accurately viewed as a giveaway to the wealthy, it is not surprising that the Trump administration is considering dangling the prospect of a new tax plan, this one focused on the middle class. But the proposals under consideration are not at all focused on the middle class and would double down on the TCJA’s failed approach.

Instead, Congress and the administration should pursue tax reform that rebalances the tax system by increasing taxes on the wealthy and corporations, who are not paying their fair share. To benefit many of the people who were left out of the TCJA, policymakers could make the child tax credit fully refundable and strengthen the earned income tax credit. Creating a refundable matching credit could help increase middle-class savings. And adopting proposals that reverse special tax treatment for the wealthy would create a fairer and more progressive tax code. In other words, Americans need a different approach than the Trump administration’s Tax Cuts 2.0 plan.

Galen Hendricks is a research assistant for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress. Seth Hanlon is a senior fellow at the Center.

* The 22 percent bracket begins at $80,251 of taxable income for married couples filing jointly. Couples can deduct the standard deduction of $24,800 from their AGI—or their itemized deductions, if greater—to arrive at taxable income.