An epidemiological threat such as the new coronavirus, which causes the disease COVID-19, can have disruptive effects on the economy. It can disrupt the global supply of goods, making it harder for U.S. firms to fill orders. It can also waylay workers in affected areas, reducing labor supply on one end and on the other slow the demand for U.S. products and services.

International Monetary Fund Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva says the outbreak is the world’s “most pressing uncertainty.” The economic disruptions caused by the virus and the increased uncertainty are being reflected in lower valuations and increased volatility in the financial markets. While the exact effect of the coronavirus on the U.S. economy is unknown and unknowable, it is clear that it poses tremendous risks.

Policymakers should therefore immediately undertake a number of steps to address any economic fallout from the virus. The burden of meeting this challenge falls squarely on Congress and the Trump administration. To its credit, the Federal Reserve has aggressively cut interest rates, but monetary policy will likely have a very limited effect since interest rates are already low and have been so for some time. To put the U.S. economy on steady footing, CAP recommends that Congress and the Trump administration engage in fiscal stimulus and embrace five key principles for economic policy action in response to the coronavirus:

- Do no harm

- Put more, not fewer, resources in public health efforts

- Assure businesses that things will be fine if the virus hits their sector and remediate harm when necessary

- Calm financial markets

- Ease the risks for households and vulnerable populations

The risks to the economy from the spread of the virus can be contained—even if the virus cannot. Congress and the Trump administration, however, will need to act quickly and communicate their actions clearly to ensure that the U.S. economy faces a more certain future.

Assessing the economic impact of COVID-19

In order to assess the possible impact of the coronavirus on the economy, it is important not only to focus on the epidemiological profile of the virus but also on the ways that consumers, businesses, and governments may respond to it. COVID-19 will most directly shape economic losses through supply chains, demand, and financial markets, affecting business investment, household consumption, and international trade. And it will do so both in traditional, textbook supply-and-demand ways and through the introduction of potentially large levels of uncertainty.

Economists have been using the SARS epidemic to put the coronavirus outbreak in context. The 2003 SARS epidemic is estimated to have shaved 0.5 percent to 1 percent off of China’s growth that year and cost the global economy about $40 billion (or 0.1 percent of global GDP).The coronavirus epidemic, which like SARS originated in China, differs in a few key ways. China’s economy accounted for roughly 4 percent of the world’s GDP in 2003; it now commands 16.3 percent. If the coronavirus has a similar effect on China as SARS, the impact on global growth will be worse. Moreover, China’s growth is weaker than it was in 2003—after years of rapid economic development, China’s growth stands at 6 percent, the lowest it’s been since 1990. Its confidence had been shaken by the dual effects of general economic deceleration and the U.S.-China trade war escalation. Even before the epidemic, China’s Purchasing Managers’ Index was already showing signs of contraction. The February reading slowed from 50 to 35.7, a level in line with that of November 2008 during the global financial crisis. The economic fallout from the coronavirus could rattle China’s economy further and dampen global growth.

The coronavirus spreads more quickly than SARS, but, so far, seems to have a lower mortality rate. For its part, China responded more quickly to the coronavirus outbreak than it did with SARS, employing unprecedented confinement measures in areas such as Wuhan. These measures, while prudent, have created short-term economic pain on the supply-and-demand side.

Outside China, the outbreak has also affected global supply chains, as other governments have also taken immediate steps to slow the spread of the virus. The Harvard Business Review predicts that the peak of the impact will occur in mid-March, “forcing thousands of companies to throttle down or temporarily shut assembly and manufacturing plants in the U.S. and Europe.” This again will disrupt global supply chains as well as demand for goods and services in the affected economies. These disruptions make it more difficult for companies in the U.S. and elsewhere to bring their goods to customers, and these companies will reduce exports from the U.S. to the rest of the world in the coming months.

Furthermore, households, companies, and governments alike are deeper in debt now than they were when SARS hit. For example, the U.S. nonfinancial corporate debt of large companies is currently around $10 trillion, up from around $4.8 trillion in 2003. Deutsche Bank released analysis showing the world’s major economies harboring the highest debt levels of the past 150 years, with World War II as an exception. They all still need to continue repaying that debt, even if jobs, customers, and tax revenues decline in a weakening economy. These fixed costs then will leave less money to spend on other things. Large amounts of debt often exacerbate an economic slowdown, especially if central banks can do little to ease that burden by cutting interest rates.

The world looks different from the last global virus outbreak in 2003. Global growth is already slow, and financial markets already have very low interest rates, which means that central banks in almost every major country have little ammunition with which to mitigate any potential economic fallout. This puts greater pressure on governments to use the power of their purse to counter the economic fallout from the coronavirus. While the fallout from the coronavirus will disrupt supply chains and global demand that could also affect the U.S. economy, the current situation also creates a lot of uncertainty over the longer term. Congress and the Trump administration can do a lot to counter the risks associated with the spread of the virus by engaging in fiscal policies (deficit spending) that will provide relief to affected populations and mitigate disruptions to U.S firms.

Supply chain disruptions make it difficult for U.S. firms to finish their products

Disruptions to global supply chains are one of the clearest effects of the coronavirus. Looking more closely at global supply chains, there have already been significant disruptions, with the list of manufacturers outside of China forced to decrease production in their plants growing longer every day.

As noted earlier, China has shut down factories in areas affected by the virus as a preventive measure, causing supply chain disruptions and affecting the mobility and near-term employment prospects of migrant workers.

These disruptions could further spread. As the virus has moved outside of China along with the efforts to contain it, it is possible that many workers around the world may not be able or willing to show up at work, further reducing economic activity. The viral outbreak in northern Italy, for instance, has shut down a firm that is the supplier of electronic parts to automakers across the European Union, meaning auto plants in several countries may need to close. This kind of widening of supply chain disruptions to suppliers of intermediate goods outside of China will make it increasingly difficult for U.S. firms to substitute products from other countries for the missing inputs from China.

How much this affects U.S. firms will depend on how tightly they manage their supply chains. Many firms manage the time between needing new supplies from China and putting them into their own production with very short lead times—often weeks and not months. These companies will feel the effect of factory shutdowns in China relatively quickly. These challenges affect not just traditional industries such as car manufacturing but also increasingly high-tech industries such as smart phones and computers. As a consequence of these supply chain disruptions, U.S. firms cannot finish their own production and thus cannot bring their products to customers. The result is reduced economic activity and growth.

Consumers are buying fewer things as they worry about the virus and its spread

The virus will not only affect supply, but some sectors of the U.S. economy may also experience declines in demand—and big reductions in revenue—because of the overall effects on the economy. There are two separate effects to consider. First, people will buy less of some goods and services because they are afraid of potential exposure to the virus. For example, they may be less willing to travel or go out to eat. The result is that air travel and hotels could feel a real pinch. Already lessened demand on food and beverage industries seems to be occurring. As Americans feel increasingly uneasy about the spread of the virus in the country, it is foreseeable that they will further cut back on some goods and increase their emergency savings instead.

Second, when firms are forced to close, workers likely will receive less money than they otherwise would have expected and, in some instances, will receive no pay. As a result, these workers will have less to spend, again cutting overall demand. A fall in demand that follows a supply shock constitutes a one-two punch that will further contract economic activity, although the size of these effects is largely unknown.

Mass flight cancellations to and from China—which has been designated as a “do not travel” destination in the United States—means almost no one is traveling to China and, more importantly for U.S. firms, Chinese tourists are not traveling overseas. A consulting firm estimates that the United States will lose 1.6 million visitors from mainland China, with an associated decrease in spending of $10.3 billion dollars. Multinational companies and luxury goods makers who rely on Chinese consumers have already suffered and had to close stores. As such effects proliferate around the world, U.S. exporters will find it harder to sell their wares around their globe, which will have negative repercussions for U.S. growth and jobs.

Meanwhile, the U.S. anticipates lower imports from China. The last quarter of 2019 saw low imports, exports, and international trade. There is a risk of a sizeable negative demand shock if the public overreacts to the coronavirus outbreak.

Uncertainty over the virus and its economic effects can damage the economy

As much as economists think about risk-taking as a key driver of the economy, an economy only works if risks are largely known. But unknown risks, or uncertainties, can have a larger, more paralyzing effect.

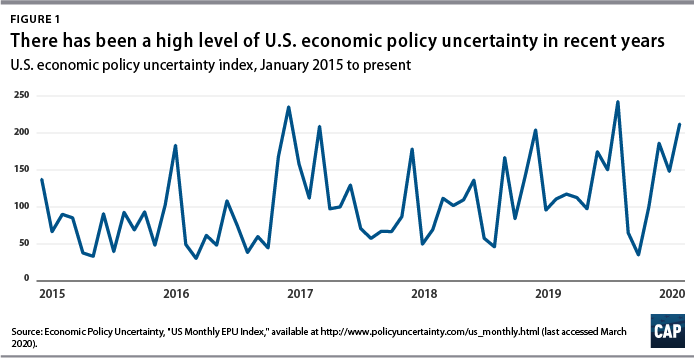

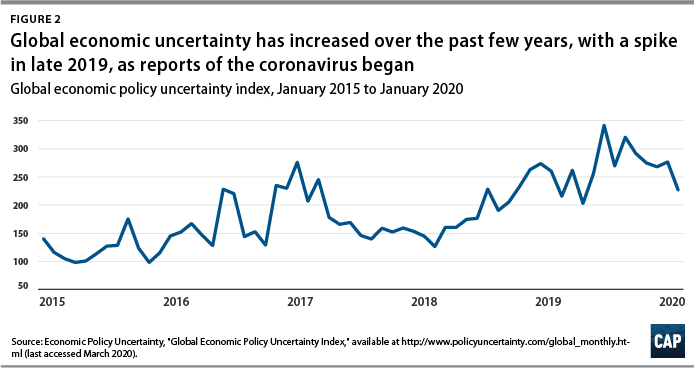

The current U.S. domestic economy—with its strong labor market and consumption levels but concerningly low inflation and investment—already exhibits a heightened sense of uncertainty. Political polarization and conflicting policies on regulation have led to firms thinking twice before investing or expanding. Both a global and U.S. economic uncertainty index, developed by economists from Northwestern, Stanford, and the University of Chicago note an all-time high in August 2019.

In addition to the already high level of policy uncertainty, the effects of the coronavirus outbreak have a commonality with the 2008 financial crisis, specifically, its unknown magnitude. There are uncertainties about the scale of the virus, contagion rate, mortality rates, risk of incidence, and more. On top of the usual online disinformation and swirl of conspiracy theories, there are questions about the accuracy of the health statistics coming from China, in part because of China’s history of providing less-than-credible numbers related to its economy. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell remarked that it’s “very hard” to understand China’s economy. That issue of credibility has only become more challenging during this crisis and it makes assessing the impact of the virus on the global economy that much more difficult.

How may a heightened sense of uncertainty affect the economy? It could affect businesses, households, and financial market participants. Businesses may hold off on investments because they don’t know what happens to supply chains as well as their domestic and international customers. Internationally, it is not known where and how far the virus will spread. This makes it hard or even impossible to assess the effects on supply chain and demand disruptions discussed above. But if these effects are difficult to evaluate, businesses will not know whether they should continue with planned or even new investments. Yet, any slowdown of business investment in the United States would come after investment spending by U.S. firms has already fallen from March to December 2019.

Businesses are not the only ones that could pull back amid uncertainty. Households, worried about contracting the virus, could cut spending on some items such as traveling and going out. Moreover, this health risk poses a real economic risk, as many households have inadequate health insurance, which could leave them with large doctors’ bills when they get sick. And, most Americans do not have paid sick leave, meaning if they get sick from the virus and need to stay home, they will not get paid. In light of the risks, many people will view it as good economic precaution to avoid activities that increase exposure to others. On an economywide scale, though, this means less spending and thus less growth.

Banks and other financial institutions may restrict and reprice credit because they cannot properly assess short-term risks to particular borrowers, sectors, or countries. Less credit availability could make it harder for businesses, especially smaller ones, to invest and grow. And, some potential home buyers could find it harder to get a mortgage. Credit market uncertainty could then exacerbate the demand fallout from the coronavirus.

There is also an international wrinkle to growing uncertainty. International financial investors could become worried about the unknown risks to the global economy from the coronavirus. They could look for the comfort of a safe investment. Traditionally, U.S. treasuries are seen as very safe investment. However, more money coming into the United States from abroad typically strengthens the U.S. dollar, and a stronger U.S. dollar will eventually make U.S. exports costlier, making it more difficult for U.S. firms to compete globally.

Supply chain disruptions, demand contractions, and global economic uncertainty happen against the backdrop of many firms and households straining under large amounts of debt. This debt has to be repaid even if the economy slows. This continued debt service then leaves less money for businesses and households to spend when their incomes drop. High debt levels will exacerbate the economic fallout from the virus.

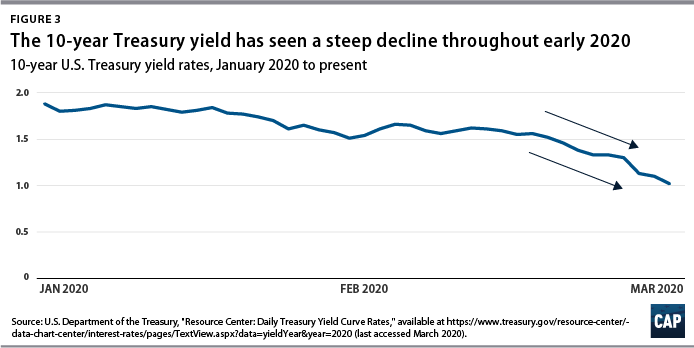

Interest rates and stock price decline as economic uncertainty takes hold

U.S. interest rates have recently fallen to historic lows in a sign of increasing economic uncertainty. The 10-year Treasury yield fell from 1.69 percent to 1.50 percent in the last week of January after remaining steadily around 1.7 percent to 1.8 percent throughout 2019 and early 2020. The decline continued through February, and for the first time in 150 years, the yield rate dipped below 1 percent on March 3.

The abnormal decline has increased calls for action from Wall Street, demanding that the White House and Congress to do something. The 10-year yield rate—often looked to as a fear index of the economy—clearly reflects the uncertainty and instability caused by the coronavirus and lack of appropriate response.

Prices on bonds with a range of maturities reflect an increasing possibility of a recession. In technical parlance, the yield curve has become inverted. Shorter-term interest rates are now higher than longer-term interest rates—the opposite of what happens in normal economic times. Such inversions are typically taken as a sign that financial markets worry about the longer-term outlook for the economy. Financial markets now see a growing risk of a recession. In the same vein, lower long-term interest rates mean that financial markets expect the Fed to cut interest rates, which are already low, to reduce the risk of a recession.

Financial markets, however, clearly worry that Federal Reserve action on interest rates may not be enough. The federal funds rate—the main interest rate that the Federal Reserve seeks to influence—has already been low. Moreover, longer-term interest rates—such as mortgage rates that matter for economic activity, including people buying houses—have fallen even without the Fed cutting rates. In addition, households hold a lot of consumer debt—student debt, car loans, and credit cards—where interest rates do not appear to react much to what the Fed is doing. That said, the effect of Federal Reserve bank interest rate cuts will be limited.

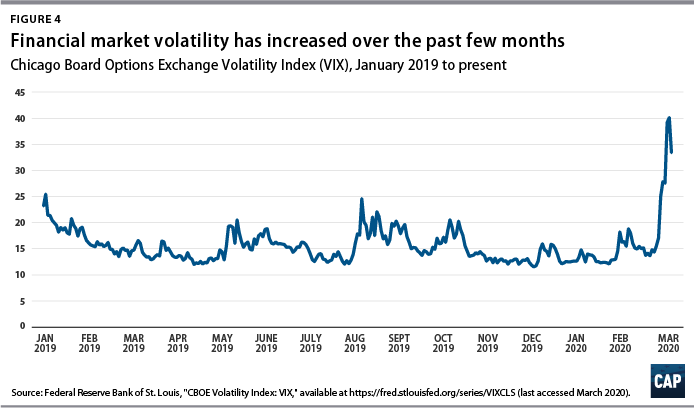

All these factors worry the stock market as the future outlook for the economy—and thus the outlook for profits—becomes murkier. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, S&P 500, and the Nasdaq composite all fell into correction territory at the end of February, representing their worst weekly skids since 2008. Stock market conditions are expected to remain volatile as measured by the Volatility Index (VIX).

Data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis shows volatility spiking abnormally in mid-February, as global panic surrounding the outbreak starts to set in. The index jumped from around 15 to almost 40 within a month. Such volatility has led corporate borrowers, who were looking to take advantage of favorable credit conditions to refinance loans, to withdraw their loans from the market and wait for stabilization. According to the Harvard Business Review, volatility “has signaled the greatest strain” on the valuation of risk assets, setting up volatility levels on par with the most major economic disruptions of the last three decades—barring the 2008 financial crisis.

5 core economic principles to inform policy in response to the coronavirus

The coronavirus puts the spotlight on policymakers to counter the risks of the virus in a quick, constructive, and effective way. It is imperative for policymakers to keep cool heads and take steps to ensure that the disruptions to workers, individual businesses, and sectors—which will cascade through the economy because of interconnectedness—are minimized while not interfering with efforts to deal with the epidemic. To that end CAP recommends five principles for economic policy action.

Do no harm

The Trump administration must find one voice and stop adding to the confusion. Moreover, the administration must to stop attacking the very programs Americans need right now: paid leave, public health insurance, SNAP, and other social programs. In its early 2020 budget proposal, the Trump administration sought to cut Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funding by 16 percent; cut $85 million from the Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases program; and had the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) cut $25 million from the Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response along with another $18 million from the department’s Hospital Preparedness Program. The latest budget proposal, modified to address the coronavirus outbreak, asks for $1.25 billion in new emergency funds for preparation and response efforts and to divert another $1.25 billion from other federal programs. It is imperative to change the message from cutting funding for public health, planning, and preparedness and instead articulate clear and decisive support of public efforts to contain the outbreak, minimize harms, and ensure investments in public health and emergency preparedness.

Put more, not fewer, resources in public health efforts

Potentially massive externalities related to epidemics alter conventional economic thinking. For example, many medical services that providers would normally charge for should be highly subsidized and delivered free (or close to free) and at a minimum of inconvenience to users. The Trump administration should consider immediate efforts to subsidize detection, treatment, and eventually immunization. Reimbursements could be a way of accomplishing this. Specifically, in terms of lowering barriers to testing, the government should make it clear that testing will be free (or at least not too expensive) and that people should not fear hospitalization (as undocumented people sometimes do).

The federal government needs to identify crucial medical supplies to deal with the outbreak and make sure that production will meet demand. Production and stockpiling of facemasks and protective gear for medical workers, and saline bags to treat patients, must be organized with government financial support. In addition, since many of the active ingredients in generic pharmaceuticals are made throughout the world—in places such as India, China, and the Czech Republic—the federal government needs to coordinate with domestic drug manufacturers to make sure the supply of many lifesaving drugs is not disrupted.

Policymakers should consider providing relief to hospitals and health care providers. It is unrealistic to think that health care providers won’t face financial strain in the event of a major outbreak or pandemic. Moreover, pandemics affect everyone, and many of the patients in need of acute care may be uninsured. Failure to treat these patients would produce large, negative health and economic externalities. Thus, pandemic preparedness cannot be approached by relying on standard health care business models. The spending necessary to expand capacity during such a public health crisis should come from the federal government, principally through the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and, ideally, informed by a robust interagency working group with HHS, CDC, and other relevant executive agencies.

Assure businesses that they will be fine if their sector is hit by the virus and remediate harm when necessary

Beyond the health sector, other industries necessary for the well-being of U.S. citizens may also need direct federal support. For example, a common response to natural disasters is panic buying in food stores, reflecting fear that supplies may not last. If the effects of the outbreak on food processors and retailers are severe, that sort of heightened anxiety will reappear—and perhaps for good reason. The government needs to consult with major food retailers and their suppliers to plan for possible disruptions in deliveries all along the food supply network and provide direct financial support to ensure that food supply does not become a serious problem.

Congress and the administration should consider measures that would provide immediate and direct relief where it is needed most. For example, in areas where the local, state, or federal government has mandated quarantines, the federal government could provide low-interest loans to small businesses for their associated costs and loss of profits. This will ensure that small businesses stay in business and that they do not have to let employees go or cut their pay. If the Trump administration can do three rounds of farm bailouts due to the trade wars, the government can certainly offer some better-designed insurance program to sectors and firms affected by the fallout from the virus.

Targeted relief to sectors heavily affected in a direct way serves both to ensure minimum service levels, minimize supply chain disruptions, and avoid credit events that could spread across the economy.

Calm financial markets

The spread of COVID-19 has begun to affect financial markets, but it is uncertain how severely the coronavirus will strain the broader financial system moving forward. As financial markets become more volatile, and more economically vulnerable actors suffer increased difficulties to meet financial contracts, it will be important to act swiftly in order to avoid any disruptions in the chain of payments and too much risk-averse behavior.

The Federal Reserve cut its benchmark interest rate by half (.5) a percentage point on March 3 in a move that was widely seen as a reaction to the coronavirus. Other central banks have already lowered interest rates or are considering doing so. The Federal Reserve should adopt an accommodative monetary policy stance and should consider using all tools at its disposal, including its emergency lending authorities. But as interest rates are close to zero in many large markets, there is limited scope for further decreases, so more creative instruments such as quantitative easing may be warranted. Inflating financial asset prices (such as the stock market) should not be a main goal in this context.

The federal government and regulators should monitor financial markets closely and prepare for possible market stress; credit events; or sudden drops in credit supply or in liquidity in markets such as overnight repurchase agreements (repos) and intervene where it is sensible to do so.

Moreover, financial regulators should carefully monitor the ongoing impact of COVID-19 on broader financial stability. If, for example, community banks in hard hit areas are unable to meet commercially viable business loans because they are capital constrained, a program to temporarily purchase preferred stock in these banks would allow them to meet local needs and keep good businesses operating.

The Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC)—a postcrisis body of financial regulators—should immediately convene a meeting to discuss the risks COVID-19 may pose to the financial system. The FSOC should task its research arm—the Office of Financial Research (OFR)—to assist with this monitoring and analysis. If the COVID-19 outbreak leads to severe stress at financial institutions and markets, financial regulators should stand ready to use the emergency authorities under their respective jurisdictions. It is important to note that the officials currently leading the financial regulatory agencies were not in office during the 2007-2008 financial crisis and may not be intimately familiar with the mechanics and protocols associated with their respective emergency authorities. To that end, the FSOC could organize a wargaming exercise to ensure financial regulators are not caught off guard if the health of the financial system does deteriorate.

It is important to emphasize that financial regulators should refrain from relaxing critical regulatory and supervisory safeguards during this period. Weakening financial stability rules for large banking institutions would undermine the core resiliency of the financial system and increase risk to the real economy.

Finally, as the coronavirus advances, it will be optimal to aim for international cooperation on economic policy matters, including financial policy. Coordinated responses will lower the likelihood of beggar-thy-neighbor policies and accusations of currency manipulation. International cooperation and coordination should also help address supply chain issues, especially in crucial supplies such as medicines.

Ease the risks for households and vulnerable populations

It will be important to reduce the impact that this outbreak with have on the financial stability and prosperity of households, particularly those who are already vulnerable. Many workers do not have health insurance, and roughly 27 percent of private-sector workers did not have access to paid sick days in 2019. Given that this is unlikely to be the last health crisis Americans will experience, the United States should adopt a guaranteed paid sick leave policy as soon as possible, just as virtually every other developed country has done. In the event of a major health crisis that involves extended sick leave, the federal government could support employers with the cost of providing paid sick time or help workers by expanding benefits through the unemployment insurance system. This would ensure that employees can recover from COVID-19 or care for a sick family member without losing their job or pay while also benefitting the businesses where they are employed.

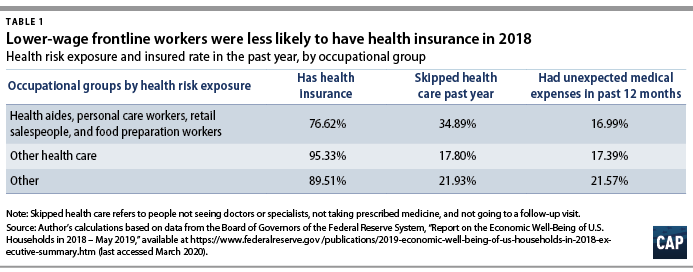

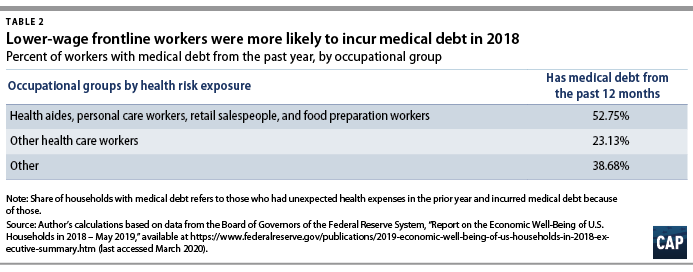

Being uninsured or underinsured, combined with limited or no paid sick time, makes people particularly financially vulnerable. For instance, lower-wage frontline workers who work in jobs where they interact with other people—such as health aides, personal care workers, cooks and servers, and retail sales people—were less likely to have health insurance and more likely to incur medical debt due to an unexpected health event than other workers in 2018. Almost one-fourth of these workers, 23.4 percent, did not have health insurance then, compared to 10.5 percent of other workers and 4.7 percent of health care workers, such as doctors, nurses, and technicians. (see Table 1) Even though the share of lower-wage frontline workers that had unexpected health expenses in 2018 was less than that of other groups of workers (see Table 1), more than half of those frontline workers with unexpected health expenses ended up with medical debt compared to only 23.1 percent for other health care workers and 38.7 percent of all other workers. (see Table 2) Health care emergencies can quickly translate into financial burdens when people lack health insurance and the ability to take time off. The 14 states that have yet to adopt the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion should do so immediately, which would result in more than 2 million low-income people gaining comprehensive health care coverage.

Congress and the administration should also mitigate the economic harm to households. This will also have the important effect of supporting consumption—the most important pillar of the economy.

Congress could take several steps to help vulnerable households. These would include ensuring free—or affordable to the patient—access to testing and treatment for the coronavirus and protecting patients from surprise bills. Other ideas for temporary assistance could include getting cash into the hands of average people. This could be done through a payroll tax holiday or through direct cash payments. Providing financial assistance to vulnerable individuals in times of hardship ensures that they can afford the basic everyday necessities; retain a measure of control over their own lives; and avoid the dire consequences of financial disaster. Putting cash in the pockets of households increases consumption and can motivate businesses to invest more. Increased consumption and business investment have a direct positive effect on economic activity and can ignite a virtuous circle of economic growth. Consumption and investment are the cornerstone of a full economic recovery.

Conclusion

With the spread of the coronavirus, the United States is facing a potential “black swan event”—an extremely rare and unpredictable incident that has potentially severe consequences. Therefore, it is important to act swiftly and in meaningful ways to minimize the fallout from this shock. Now is precisely the time for deficit spending: Low interest rates make it cheap and easy for the government to finance itself while limiting the potency of further monetary stimuli from the Federal Reserve. Therefore, it is incumbent upon the federal government to provide fiscal stimulus to ignite economic activity. In other words, the government needs to engage in sizeable spending and investment in key areas of the economy in order to increase economic activity; minimize disruption to the health and prosperity of the population; and to limit the effects on supply chains and the business sector. The five principles for economic policy action outlined in this report provide a roadmap for meaningful and decisive fiscal action that will help the economy regain its footing.

It is important to note a policy prescription that is clearly not included in the list of recommended actions outlined above: a broad-based tax cut that favors corporations and the wealthy. There is evidence that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) constituted a large corporate-tax windfall that went mostly to already wealthy individuals with little evidence that it well to middle- and working-class families. It did not spur large levels of investment or growth and ballooned the fiscal deficit. The tax cuts recently proposed by the Trump administration will be very costly and will not directly or efficiently address the economic fallouts from a potential widespread coronavirus outbreak in the United States. Such proposals, including further cuts to the corporate income tax, would provide a windfall to many large and profitable corporations and other businesses—regardless of whether or not they have been meaningfully impacted. Most of these firms are already benefitting from enormous tax cuts enacted in the 2017 tax law. Redoubling this mistake will distract from other efforts and waste resources that are urgently needed for the purposes outlined in this report.

A potential sudden stop in activity, coupled with heightened uncertainty, may expose structural vulnerabilities in certain households and markets. A decisive and rational response along the lines of the five principles outlined here will minimize economic risks and contribute to a speedy recovery.

Andres Vinelli is the vice president for Economic Policy at American Progress. Christian E. Weller is a senior fellow at American Progress and a professor of public policy at the McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. Divya Vijay is a special assistant for the Economic Policy team at American Progress.

To find the latest CAP resources on the coronavirus, visit our coronavirus resource page.