This column contains an update.

During the week of December 16, the U.S. House of Representatives is expected to consider H.R. 5377, the Restoring Tax Fairness for States and Localities Act, which was reported out by the Committee on Ways and Means on December 11.* The bill would temporarily repeal the $10,000 cap on deductions for state and local taxes (SALT) imposed by the Trump tax law of 2017. While this law, known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), was fundamentally misguided and needs to be overhauled, fully repealing the SALT deduction limit would cost hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue and overwhelmingly benefit the wealthy, not the middle class.

H.R. 5377 offsets the substantial revenue loss from repealing the SALT cap for 2020 and 2021 by restoring the pre-TCJA top individual tax rate of 39.6 percent and lowering the income thresholds above which the top rate applies. Yet dedicating that revenue to repealing the SALT cap would waste the opportunity to invest it in other, more progressive priorities. And if policymakers intend to extend the SALT cap repeal beyond 2021 without increasing deficits, it would require additional offsets that could be dedicated to other priorities. Under the bill, the offsetting changes to the top rate would be in effect from 2020 through 2025—after which the major individual tax provisions of the TCJA are scheduled to expire altogether—while the restoration of the SALT deduction would be in effect only through 2021.

How the TCJA changed the SALT deduction

Before the TCJA was enacted in 2017, the tax code generally allowed taxpayers to deduct all of the income and property taxes that they paid to states and localities. However, the SALT deduction is an itemized deduction, which means that taxpayers can only claim it if they do not claim the standard deduction. Before the TCJA, only about 26 percent of taxpayers itemized their deductions, with higher-income taxpayers being the most likely to do so.

The TCJA of 2017 made three major changes affecting the SALT deduction.

First, it capped the SALT deduction at $10,000, meaning that taxpayers who pay more than $10,000 in state and local taxes can only deduct that amount. Second, the law raised the standard deduction to $12,000 for singles and $24,000 for couples—adjusted to $12,200 and $24,400, respectively, in 2019 due to inflation. With these two changes, even fewer taxpayers will itemize: only about 11 percent overall, according to the Tax Policy Center.

Third, the TCJA drastically rolled back the alternative minimum tax (AMT). Under the AMT, taxpayers do a separate tax calculation with many fewer available deductions and pay the AMT to the extent that it exceeds their regular taxes. Before the TCJA, the biggest deduction denied by the AMT was SALT, which means that millions of taxpayers had their SALT deduction effectively recaptured. Before the TCJA, more than 5 million taxpayers paid the AMT, 96 percent of whom had incomes of more than $200,000. Now, only about 200,000 do so.

In the wake of these changes, the tax cut from repealing the cap on the SALT deduction would be extremely regressive.

Tax cuts from SALT cap repeal would go overwhelmingly to the wealthy

If the SALT cap were repealed, virtually all low-income taxpayers, and the vast majority of middle-income Americans, would still opt to claim the standard deduction. In fact, according to the Tax Policy Center, 98.6 percent of taxpayers with incomes of less than $100,000 and 84 percent of those with incomes between $100,000 and $200,000 would see no benefit from the SALT cap repeal.

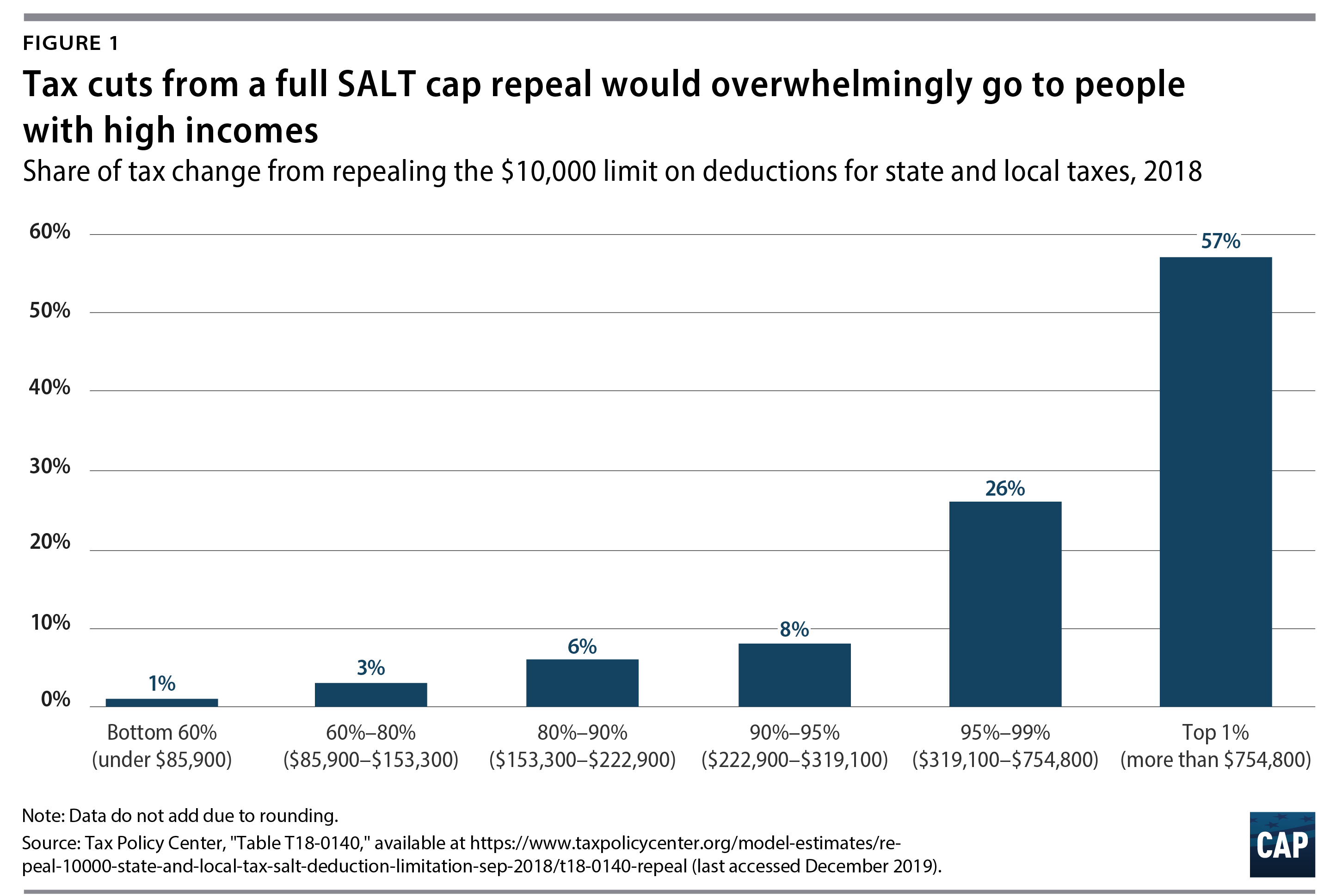

There are some middle-class taxpayers who would see some benefit from the repeal, but the tax cut they receive would pale in comparison to that received by the superwealthy, who in some cases would be able to deduct millions in state and local tax payments. For the 16 percent of taxpayers with incomes between $100,000 and $200,000 who would benefit from the SALT cap repeal, their average tax cut would be about $800. By contrast, 93 percent of millionaires would benefit, and that group’s average tax cut would be nearly $50,000.** Overall, more than half of the tax cuts from the SALT cap repeal would go to the wealthiest 1 percent. (see Figure 1)

Ironically, many of these upper-income taxpayers were not benefiting from the SALT deduction before the TCJA—even if they claimed it on their tax forms—because the AMT effectively nullified it.*** Moreover, high-income taxpayers received many other tax cuts from the TCJA.

Even in high-tax states, tax cuts from SALT cap repeal would mostly go to the wealthy

A higher share of taxpayers in relatively high-tax states, such as New York and California, would benefit from the SALT cap repeal. But even in those states, few middle-class taxpayers would benefit, and the tax cuts they receive would be a pittance compared with those of millionaires.

In California, for example, according to estimates by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), only 1 percent of taxpayers in the bottom 60 percent of the state’s income distribution—those with incomes of less than $75,300—would receive any tax cut from the SALT cap repeal, while only 17 percent of those in the next quintile—those with incomes between $75,300 and $134,000—would receive a tax cut. Even for those taxpayers in the bottom 80 percent who did receive tax cuts, those cuts would average about $800, whereas the 97 percent of California’s richest 1 percent who would benefit from the SALT cap repeal would receive tax cuts averaging $76,500, nearly 100 times larger. This same dynamic holds in every state, according to ITEP’s 50-state estimates.

Over the long term, there is a channel through which SALT cap repeal could indirectly benefit low- and middle-income Americans. By allowing a SALT deduction, the federal tax code makes state and local taxes less costly for the households claiming it. As a result, these families may put up less resistance to state and local taxes, making it politically easier to raise revenue. More revenue for states and localities could lead to more investment in schools and health care, for example. And if the revenue comes from the relatively high-income households benefiting from the federal deduction, it could lessen reliance on problematic revenue sources such as fees and fines.

However, policymakers must weigh these very uncertain indirect effects against the immediate and certain windfall for rich Americans that would result from repealing the cap. If Congress repeals the deduction cap temporarily, as the legislation being considered by the House of Representatives does, it is very unlikely that there will be any indirect effects benefiting low- and middle-income families since states and localities would not adjust their fiscal policies immediately in response. In fact, some states have taken steps to raise or extend taxes on high-income residents since the passage of the TCJA, suggesting that the repeal of the SALT cap has not stifled progressive tax policy at the state level. Policymakers should also consider that federal revenue can support progressive state-level investments in health care, schools, infrastructure, or other priorities.

Conclusion

There are more important priorities in overhauling the TCJA, including the policies embedded in the legislation the Ways and Means Committee advanced earlier this year—for example, ensuring that low-income families can fully benefit from the child tax credit. If policymakers are concerned with the effect of the SALT cap on middle-class families, there are options to address it without providing enormous windfalls for the wealthy. For example, as part of a larger overhaul of the TCJA, Congress could increase the cap rather than eliminating it—perhaps only for married couples, as they can now only deduct the same amount as singles. The bill under consideration in the House provides for this kind of targeted fix for the current tax year, doubling the SALT cap to $20,000 for married couples before eliminating the cap entirely in 2020 and 2021. Congress could also adjust the cap for inflation, or raise the cap for middle-income households but phase out that increase for high-income households.

The TCJA is unfair and flawed in many ways. It is not working as advertised and needs to be fundamentally overhauled. But fully repealing the SALT cap would exacerbate its worst flaws: It would drain revenue needed for other priorities while giving even larger tax cuts to the rich. Congress should explore less costly and more equitable options.

Seth Hanlon is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress

*Update, December 13, 2019: This column has been updated to reflect House committee action on the Restoring Tax Fairness for States and Localities Act.

**Author’s note: CAP calculations use data from the Tax Policy Center based on the 2018 tax year.

***Author’s note: The high-income households most likely to pay the AMT were the biggest beneficiaries of the TCJA. Taxpayers in the 95th to 99th income percentiles—those making between $308,000 and $733,000 per year—received the largest average tax cuts relative to their income as a result of the TCJA, closely followed by the top 1 percent.