The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics will release its monthly report with October’s jobs numbers on Friday, one day after Latina Equal Pay Day. Latinas—those with Hispanic origin in the Current Population Survey—experience one of the largest gender wage gaps among all women: Hispanic women who work full time, year-round earn just 53 cents for every dollar earned by white, non-Hispanic men also working full time, year-round. This gap widens in certain states, particularly those with large populations of Latinas in the workforce. For example, in California and Texas, Latinas made 43 cents and 44 cents, respectively, for every dollar earned by their white male counterparts in 2016. This earnings gap can have dire consequences, especially when compounded by other obstacles Latinas face in the labor market.

There are a variety of factors that drive the wage gap experienced by Latina workers. One important factor is linked to occupational segregation; Latinas often work in jobs that are disproportionately female or pay very low wages. And overall, Latinas are much more likely to work in low-wage occupations than their white male counterparts. However, there is much more to the story. For example, Latinas in the 95th percentile of income earners make just 45 cents for every dollar earned by their white, non-Hispanic male counterparts at the same percentile, whereas Latinas in the 10th percentile make 85 cents compared with their white, non-Hispanic male counterparts at the same percentile. Furthermore, in a nationally representative 2017 survey addressing discrimination in America, 33% of Latinos said they have been personally discriminated against when applying for jobs because of their ethnicity; 32 percent said that they have faced discrimination regarding being paid or promoted equally; and 31 percent reported discrimination when trying to rent or buy housing. In other words, Hispanic people are confronted by other forces outside of occupational segregation that reinforce these pay discrepancies. And this is especially true for Latinas, who often face greater economic disparities than their male counterparts. Needless to say, the existence of occupational segregation does not fully explain the story of this earnings gap; other factors are at play, including instances of workplace discrimination and other barriers to upward mobility and wealth accumulation.

In addition to lower median wages, Latina and black women experience higher poverty rates than their white and Asian women counterparts. Tremendous disparities in wealth exist along both racial and gender lines. For example, single Latina women hold just one cent for every dollar of wealth owned by white women.

Greater attention to economic outcomes for Latinas and other historically disadvantaged groups should inform and guide national monetary and economic policy. While some argue that the economy has reached full employment, indicating there is little room for growth, other indicators tell a different story.

Median wage

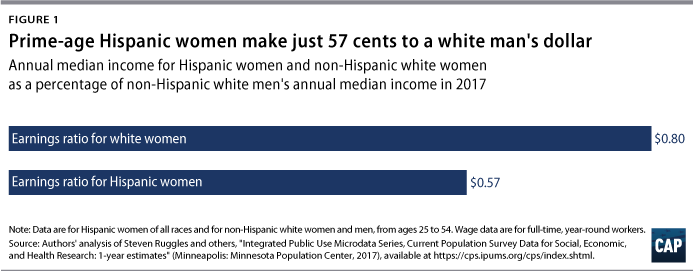

Latinas make significantly less money than most workers from other racial and ethnic groups. For example, the figure below presents the earnings ratio for white and Hispanic women ages 25 to 54—also known as prime-age workers—compared to white, non-Hispanic men. This analysis focuses on prime-age workers because they are the driving force of the economy; although, study of the gender wage gap at all ages can provide different and important insights. In 2017, prime-age Hispanic women who worked full time, year-round made 57 percent, just more than half, of what white, non-Hispanic men made in the same year, while prime-age white women made 80 percent of what white, non-Hispanic men made.

Occupational segregation

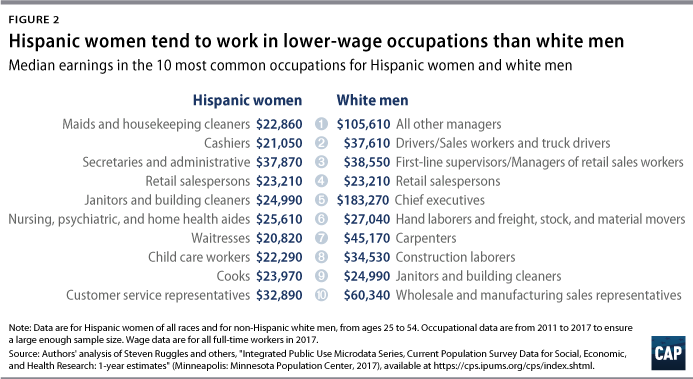

As mentioned before, a significant cause of the wage gap between Latinas and white, non-Hispanic women and men is the fact that Latinas tend to work in lower-paying occupations due to formidable structural barriers to entry and success in the labor market. The figure below displays the top 10 occupations in 2017 for Hispanic women and the corresponding median annual wages for these occupations. These median wages for Hispanic women range from $20,820 to $37,870. For comparison, the median wages for white, non-Hispanic men’s top 10 occupations range from $23,210 to $183,270.

Unemployment

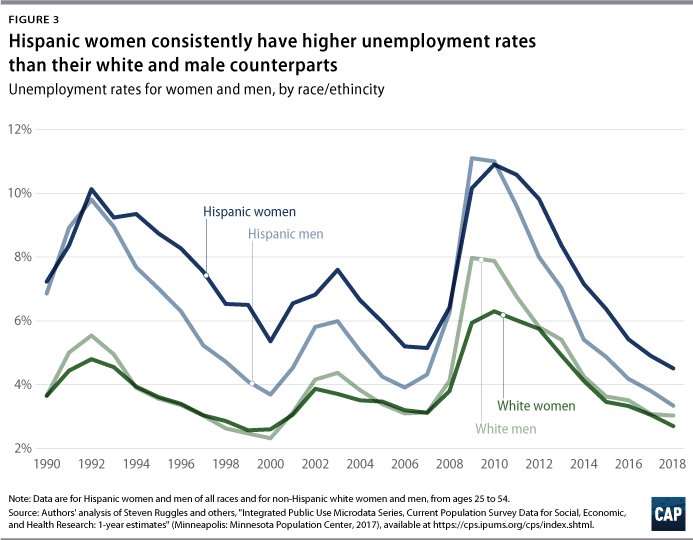

In recent history, women have had slightly lower or equal unemployment rates compared with men; however, this trend is reversed for Hispanic women. Hispanic women have higher unemployment rates than Hispanic men, while the unemployment rates of white women and men are very similar.

Part-time employment

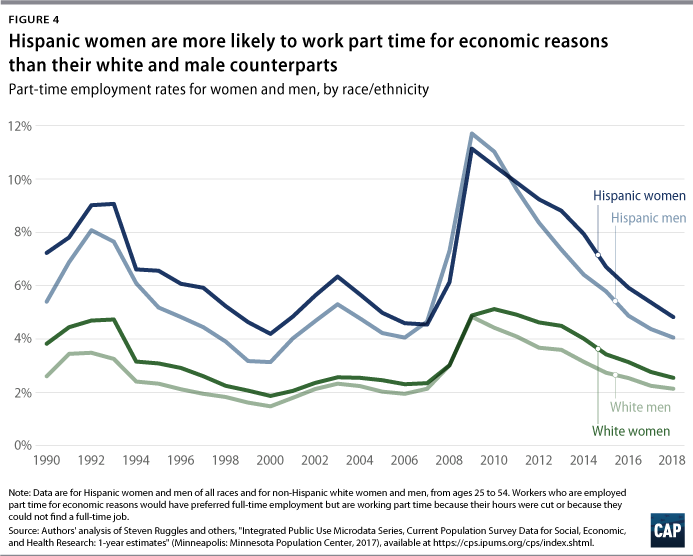

The number of workers who are employed only part time for economic reasons—meaning they are unable to find full-time work despite wanting it—remains high compared with prerecession levels. If workers are part time because their hours are cut or because they cannot find a full-time job, that indicates a labor market that is less favorable for all workers. As shown below, Hispanic people are much more likely to work part time for economic reasons than their white counterparts. In 2018, Hispanic women were more than twice as likely as their white male counterparts to work part-time for economic reasons.

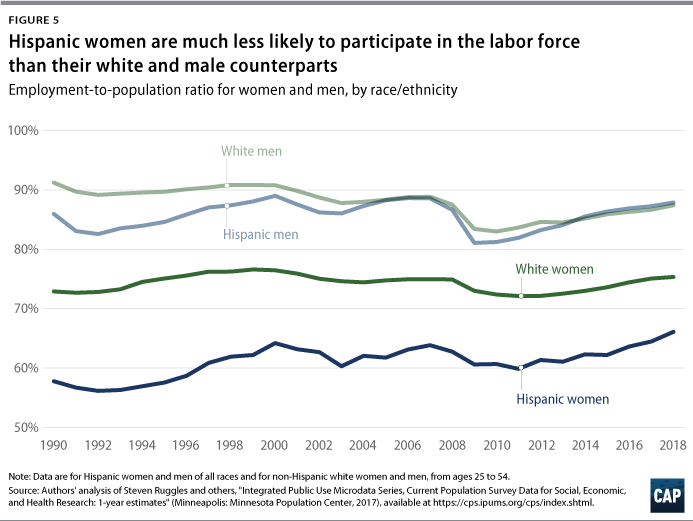

Employment-to-population ratio

Hispanic women have a much lower employment-to-population ratio (employment rate) than Hispanic men as well as white women and men. The employment-to-population ratio is the share of the population that is employed. Although Hispanic men and white men have almost identical employment rates, there is almost a 10 percentage-point gap in the employment rates between white women and Hispanic women. More research is needed to understand Latinas’ low employment rates and to answer questions such as whether it could be due to a higher likelihood of informal employment that would not be recorded in government employment data collection. Latina workers may also be less likely to respond to government surveys such as the census. This disproportional survey refusal rate is in part driven by specific fears and suspicions of deportation and authorization, as well as general distrust in government.

Conclusion

Comparatively lower pay and worse labor market outcomes compound to put Latinas and their families in an especially economically precarious position. Recent analysis has looked at the increasing number of breadwinning mothers and found that Latinas outpace white mothers as the primary breadwinners of their families. Yet despite how vital their earnings are to keeping their families afloat, women of color—including Latinas—experience larger wage gaps than white women, compounding the economic precarity experienced by Latinas in the labor market.

The structural disadvantages that Latinas face can also be a drag on the entire economy, as these workers are not able to achieve their full potential. Policymakers and economists need to make sure to consider the challenges of Latinas and other populations that face high labor market barriers when evaluating the health of the labor market and implementing policies that affect it.

Daniella Zessoules is a special assistant for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress. Galen Hendricks is a special assistant for Economic Policy at the Center. Michael Madowitz is an economist at the Center.