This column contains a correction.

Today is Moms Equal Pay Day—the day up until which the average mother would have to work to make as much as the average father made in the previous year. This year, Moms Equal Pay Day falls just two days before the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics releases employment numbers for the month of May.* Before the new numbers come out, this column analyzes the current state of mothers in the labor market. Mothers make less, on average, than fathers across states, education levels, occupations, and mothers’ ages, and researchers have found that motherhood contributes significantly to the gender pay gap. This phenomenon is known as the “motherhood wage penalty,” in which women with children face greater wage penalties compared with women who do not have children, resulting in lower wages, while fathers receive a wage premium when they have children.

While overall, full-time, year-round working women make 80 cents to a man’s dollar, mothers make only 71 cents to a father’s dollar. Additionally, recent research from the U.S Census Bureau found that the spousal earnings gap for opposite-sex married couples doubles between the two years before the birth of a first child and the year after that child is born; the gap continues to grow for the next five years.

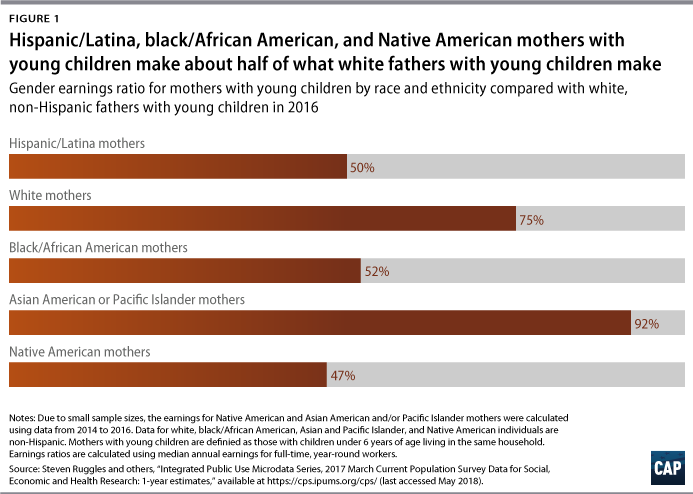

Race exacerbates these pay inequities: Black/African American and Hispanic/Latina mothers make about half of what white fathers make, and Native American mothers with young children make even less—47 percent—when compared with white fathers with young children. (see Figure 1) Additionally, single mothers on the whole earn much less than married mothers across race and ethnicity. These lower earnings combined with the lack of adequate supports—such as paid leave and affordable child care—for single mothers, who are disproportionately black and Hispanic/Latina, means that they are more likely to experience economic instability.

While mothers are less likely to be in the labor force than fathers, their participation rates have substantially increased since the 1970s: 71 percent of mothers with children under age 18 are in the labor force today, compared with only 47 percent in 1975. However, similar to the labor force participation rate of all women, the labor force participation rate of mothers has been mostly stagnant since reaching a peak of 73 percent in 2000. Lack of workforce supports that meet the needs of 21st century mothers are likely partially responsible for the recent decline in mothers’ labor force participation. The United States lags far behind other countries in terms of providing paid leave, affordable child care, and other supports that are of particular importance to parents, as well as to any worker who might require such flexibility to take care of their loved ones.

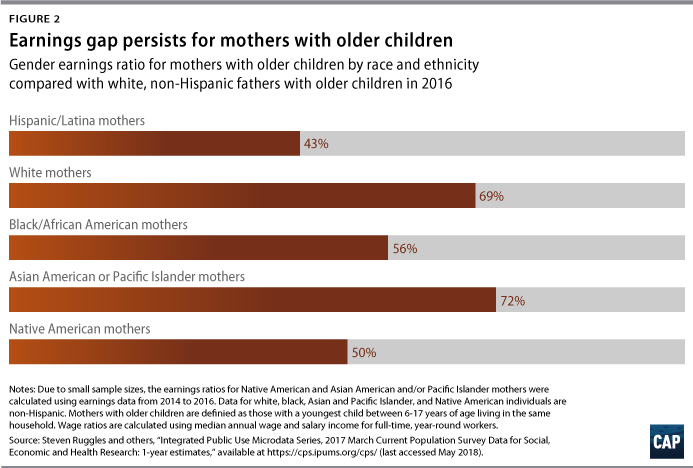

This analysis compares mothers across race to white, non-Hispanic fathers, analogous to the customary comparison in equal pay analyses. All original data analysis here for white, Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI), Native American, and black/African American women is for those who do not identify as Hispanic/Latina. It should be noted that although fathers fare better in terms of overall wages when compared to mothers, this differs by demographic—for example, Hispanic/Latino and black/African American fathers receive less of a wage premium once having a child than white fathers. Additionally, while this column groups AAPI individuals together because of sample-size issues with disaggregating the data, this likely obscures differences between subgroups.

Greater attention to economic outcomes for mothers, with a particular focus on mothers who are most disadvantaged in the labor market in terms of class, race, ethnicity, and other factors, should inform and guide national monetary and economic policy. A tight labor market that disproportionately helps those facing the highest barriers and obstacles would create job opportunities for parents who want to work. Additionally, policies promoting affordable child care, paid leave, workplace flexibility, and predictable work schedules would go a long way to help mothers achieve equality in the labor market.

Median earnings

Although the overall pay gap for all full-time, year-round working women is 80 cents to a man’s dollar, certain demographics of women in particular lag behind men. For example, black/African American mothers make just 54 cents for every dollar paid to white fathers, compared with the 71 cents that mothers overall make. Native American mothers make even less, at a national average of 49 cents compared with every dollar made by white fathers.

As shown in Figures 1 and 2 below, mothers across race and ethnicity face a gender pay gap when compared with white men, with Hispanic/Latina, black/African American, and Native American mothers facing the largest gap. Among mothers working full time, year round who have children less than 6 years old, Hispanic/Latina, black/African American, and Native American mothers make only about 50 percent of what white fathers make. Those percentages for white and AAPI mothers are 75 percent and 92 percent, respectively. The same trends can be seen for mothers with older children. However, the wage gap for Hispanic/Latina mothers is shockingly high—Hispanic/Latina mothers with children ages 6 through 17 make only 43 percent of what white fathers with children in this age range make.

The majority of the overall gender wage gap can be explained by gender differences in industries and occupations (50.5 percent), discrimination and gender stereotyping (38 percent), and work experience (14 percent). Women have less work experience than men largely because women are more likely to work fewer hours or leave the labor force completely because of family or other obligations. Additionally, women are more likely to be part-time workers. The rest of the gender wage gap can be explained by racial wage inequality (4.3 percent) and regional differences in pay (0.3 percent).

It’s important to note that the wage gaps shown in Figures 1 and 2 are only for full-time, year-round workers. These wage gaps would be much larger if they included part-time workers, since mothers are much more likely to work part time than fathers. Mothers continue to carry a disproportionate amount of unpaid household and caregiving responsibilities, which contributes to the high rate of mothers who work part time. High rates of part-time work for mothers come with distinct costs, as part-time work tends to be lower pay and less likely to offer benefits. Despite having the same levels of education and experience, for example, women who work part time earn much less per hour than their full-time counterparts.

Labor force participation

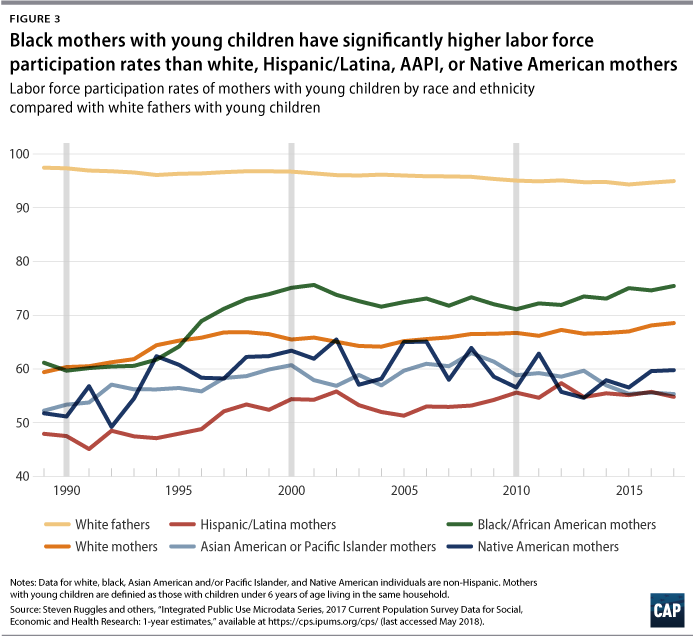

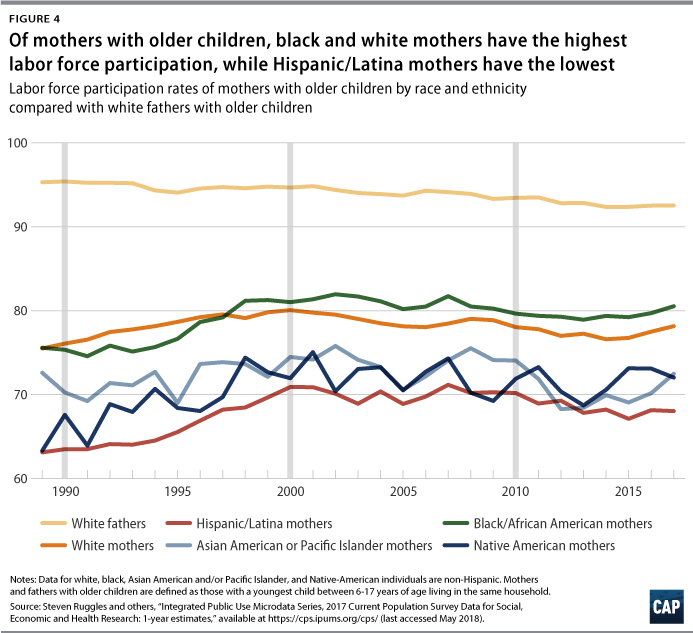

Overall, mothers with young children are much less likely to participate in the labor force than mothers with older children, while fathers with young children are slightly more likely to participate. Fathers with young children have a labor force participation rate of 95 percent, compared with the almost 93 percent rate of fathers with older children. With the exception of black/African American mothers, mothers with young children have significantly lower labor force participation rates compared with those with older children—at least a 10 percentage point drop. For black/African American women, however, the difference in labor force participation rates between mothers with older children and those with young children is only 5 percentage points.

Of all the mothers analyzed in Figures 3 and 4, Black/African American mothers with children ages 6 through 17 have the highest labor force participation rate at 80 percent (see Figures 3 and 4) However, their participation rate is still more than 10 percentage points lower than the rate for white fathers who have children in the same age group. White mothers with older children have the second-highest labor force participation rate, while Hispanic/Latina and AAPI mothers with young children have the lowest labor force participation rate, at around 55 percent.

The labor force participation rate of all mothers has increased in the past few decades, but it has increased for certain demographics more than others. Among mothers with young children, black/African American women have increased their participation the most: Their labor force participation rate has increased by 23 percent since 1989. Among mothers with older children, the labor force participation rate for Native American mothers has increased the most, at 14 percent since 1989.

The fact that black/African American women’s labor force participation changes little as their children age, as well as that black/African American mothers are most likely out of all mothers, to participate in the labor force, suggests that black/African American women may have higher labor force participation rates out of necessity due to lower wages and a greater likelihood of being breadwinners—a trend that has been true for decades. In 1970, for example, black mothers were as likely to be the sole breadwinners or co-breadwinners of their families, at 58.6 percent, as white women were for their families in 2015. This high rate of black/African American women as breadwinners likely contributes to their higher labor force participation rates, as they need to support the needs of their families. Additionally, the high labor force participation rates of black women are rooted in a variety of historical factors and barriers, including persistent racial and gender stereotypes and discrimination, that often relied on black women’s work—paid or unpaid—to sustain the broader society.

Unfortunately, little research explains why Hispanic/Latina, Native American, or AAPI women have labor force participation rates that are drastically lower than those of black/African American and white women. More research should be done on this issue—and on what can be done to provide well-paying job opportunities for Hispanic/Latina, Native American, and AAPI women.

Unemployment

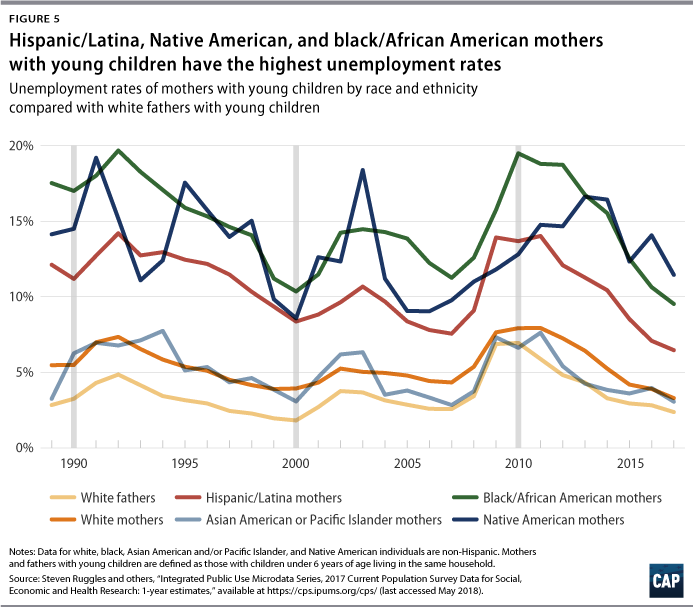

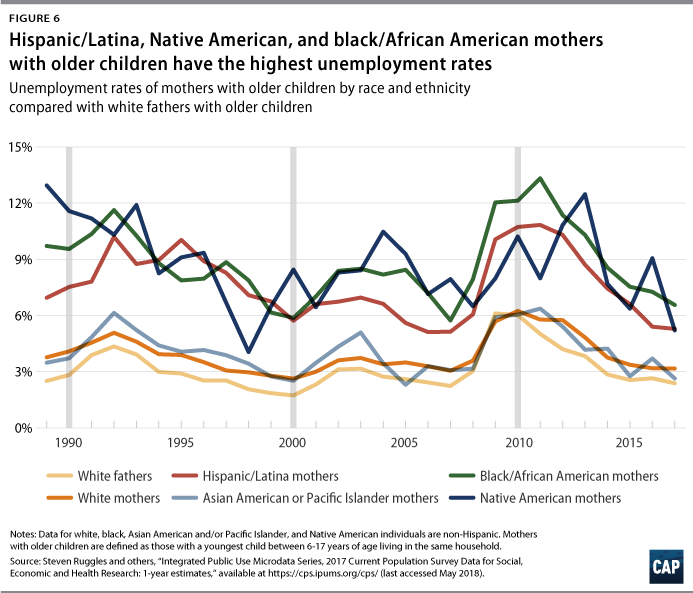

Unemployment rates are particularly high for unmarried mothers with younger children—a population that relies more heavily on work supports such as child care, the absence of which likely affects their ability to find and maintain a job. Further, structural inequities contributing to unemployment are furthered by instances of employment discrimination in the workforce, affecting both job opportunity and career advancement.

Overall, mothers with children ages 6 through 17 tend to have lower unemployment rates than mothers with children ages 5 and under. Black/African American and Native American mothers with younger children have the highest unemployment rates—9.5 percent and 11.5 percent, respectively, in 2017. White and AAPI mothers with older children have the lowest unemployment rates at 3.2 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively. It’s important to note that low AAPI unemployment likely obscures differences in unemployment rates within the AAPI population. In 2015, for example, the unemployment rate for Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander workers was more than 1 percentage point higher than the overall rate for AAPI workers.

Similar to the labor force participation trends noted above, the age of children affects the unemployment rates of mothers more than the rates for fathers. However, it affects mothers of different races and ethnicities differently. For example, the unemployment rate for black/African American mothers with young children is around 6 percentage points higher, on average, than the rate for black mothers with older children, and the rate for Native American mothers with young children is 5 percentage points higher than the rate for Native American mothers with older children. However, the unemployment rates for white, Hispanic/Latina, and AAPI mothers with young children are only slightly higher than the rates for those with older children. For white fathers, there is little difference in unemployment rates for those with older and younger children.

Conclusion

Comparatively lower pay in addition to lack of workplace supports compound to put mothers and their families in particularly precarious economic positions—especially mothers of color, who face compounding discrimination and structural inequalities resulting from both sexism and racism. Policymakers and economists need to consider these challenges when evaluating the health of the labor market and implementing policies that affect it.

Daniella Zessoules is a special assistant for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress. Annie McGrew is a research assistant for Economic Policy at the Center. Michael Madowitz is an economist at the Center.

* Correction, May 30, 2018: This column has been corrected to reflect that the upcoming jobs release reflects May data.