This column contains corrections.

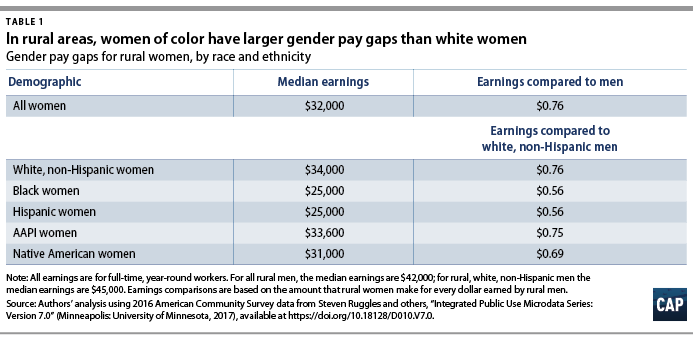

In the current debate about jobs and the working class, the conversation about rural America and rural employment often assumes that the only people who exist in—or matter to—rural America are white working men. This assumption, though, is simply wrong. In fact, women and people of color are a central part of rural America. Ignoring the diversity of rural America comes at a high cost, especially for women of color. While all rural workers earn lower wages than their nonrural counterparts, new analysis by the Center for American Progress reveals that women of color are among the lowest paid workers in rural areas with rural black and Hispanic women who work full time, year-round making just 56 cents for every dollar that rural white, non-Hispanic men make. Native American and Asian American and Pacific Islander women earn slightly more, making 69 cents and 75 cents, respectively, though these figures can mask wide variation within these communities. (see Methodology below) These numbers make clear that, regardless of where they live, all women of color are facing substantial economic challenges and that addressing the needs of rural workers requires more than focusing solely on one segment of that workforce. Rather, any policy interventions to improve employment and economic outcomes for rural workers must recognize and be responsive to the demographic differences within the rural workforce and the diverse challenges facing rural workers.

While popular media narratives often disregard this reality, a little more than one-fifth of people living in rural America are people of color, with a disproportionately high percentage of Native Americans living in rural areas relative to their share of the overall population. In fact, more than one-fifth of Native Americans live in rural communities, which is more than double the share of the white, non-Hispanic population living in these areas. This diversity is also reflected in the rural workforce. Among full-time, year-round workers in rural areas, white, non-Hispanic men comprise just less than one-half of the workforce, or 48 percent; women and people of color comprise the remaining majority. Women—including white women and women of color—make up 42 percent of rural workers, and workers of color collectively make up 17 percent of the rural workforce.

Much of the attention on rural America has focused on the lower wages and job loss facing white working-class men, but rural women across all races and ethnicities experience sizable wage gaps and significantly lower wages when compared to white men. While the wage gap for women overall stands at 80 cents for every dollar earned by men, new Center for American Progress research reveals that the gap grows even larger when rural women are compared to men overall: Rural women who are full-time, year-round workers earn a mere 64 cents for every dollar earned by men overall. Even when looking solely at rural workers—who earn less than nonrural workers, regardless of gender—the gender wage gap is larger than that of the overall population, with rural women who are full-time, year-round workers earning just 76 cents for every dollar earned by rural men.

The picture is, in many instances, direr when race and ethnicity are taken into account. Overall, black, Hispanic, and Native American women working full-time, year-round earn 63 cents, 54 cents, and 57 cents, respectively, when compared to every dollar earned by white, non-Hispanic male full-time, year-round workers, and Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) women earn 91 cents. But these figures are not the full picture. This research shows that women of color in rural communities are paid among the lowest wages in the nation, making substantially less than white, non-Hispanic men overall. When compared to all white, non-Hispanic men working full-time, year-round, black and Hispanic rural working women make just 45 cents. Native American rural working women make 56 cents and rural AAPI women just 61 cents for every dollar white, non-Hispanic men make.* As noted above, even when looking solely at full-time, year-round rural workers—where white, non-Hispanic men’s earnings are significantly lower than the earnings of their nonrural counterparts—black and Hispanic rural working women make just 56 cents and Native American rural working women make 69 cents for every dollar white, non-Hispanic rural men make. Rural AAPI women do somewhat better, making 75 cents for every dollar white, non-Hispanic rural men make, though overall wage gap figures for AAPI women often obscure dramatic differences within that community.* What’s more, the wage gap data—which are focused on full-time, year-round workers—only offer one view into economic disparities. They do not capture the economic hardship faced by part-time workers, people who are looking for work but are unable to find it, people out of the labor force, or those who are incarcerated. These concerns disproportionately affect communities of color and include sky-high rates of unemployment among Native Americans and incarceration among black Americans.

Previous research examining the gender wage gap in the overall workforce has consistently identified a mix of different factors—such as differences in work hours, lack of access to strong work-family policies, occupational segregation, and discrimination—that together fuel the gender wage gap. The data discussed herein, which often show larger gender wage gaps among rural workers, raise similar questions and suggest an urgent need for more research on the experiences of and opportunities for rural female workers. These findings also highlight the need for more and better data on rural Americans, specifically rural women of color, to assess the factors that contribute to their wage gaps, including occupational segregation, their work experiences, and the discrimination they face.

These data underscore the fact that improving economic outcomes for rural workers must include specific attention to identifying unique barriers that have widened the wage gap for many rural women, including women of color. Because their wages are so low, rural women would especially benefit from a policy agenda focused on raising the minimum wage and eliminating the tipped minimum wage. Some rural women—particularly women of color—work in jobs such as home-care workers that have been consistently undervalued with limited visibility into employer pay practices. These women could benefit from measures aimed at providing greater pay transparency and accountability, and stronger protections to challenge unequal pay practices.

Additionally, close to two-thirds of women in rural areas are breadwinners or co-breadwinners, making at least 25 percent of their families’ earnings. These women and others who manage work and caregiving responsibilities need robust, inclusive paid leave policies. The challenge for these women is compounded by the fact that rural areas often lack access to child care, thus, investing in new strategies to expand the availability of affordable, quality child care could improve the lives of working rural women as well as help more rural women participate in the workforce. Rural women also lack access to women’s health care services, including reproductive health care, which are essential for women to live healthy lives and make informed decisions about their health and family needs.

Despite the urgent need for these policies—and promises to improve economic outcomes for all women and rural Americans—President Trump’s administration has failed to deliver on these promises and has, in fact, pursued policies that are detrimental to women’s economic advancement, such as proposing a rule to steal billions of dollars from tipped workers and halt the pending collection of critical equal pay data. Instead, rural women need a robust policy agenda that strikes a blow against economic and racial inequity and injustices and advances a vision that builds an equitable economy and society where everyone can participate and thrive.

Methodology note: Unless otherwise noted, this analysis uses data from the 2016 American Community Survey. The wage gaps reported compare median earnings, which include wage, farm, and business income, for full-time, year-round workers. People are considered to be living in rural areas if they are living outside of a metro area as defined by the Census. This analysis largely focuses on comparing the earnings of rural women to rural men to account for differences in cost of living, education levels, and industries in rural versus non-rural areas. Data used are the latest available from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series USA interactive data tool.

Katherine Gallagher Robbins is the director of policy for the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress. Jocelyn Frye a senior fellow at the Center. Annie McGrew is a research assistant for Economic Policy at the Center.

*Correction, April 10, 2018: This column originally misstated the demographic groups whose earnings were compared. It has been corrected to describe the accurate wage gap analyzed in these sentences.