Historically, planners and elected officials have prioritized building roads and highways exclusively for vehicles at the expense of other transportation modes, such as walking and bicycling. Federal regulations and outmoded approaches from some state officials inhibit communities from designing their roadway networks to serve people who want to walk, bicycle, or take public transportation. As the ability to walk and bike becomes more desirable, communities will need to develop the proper infrastructure to accommodate them safely.

Prioritizing motor vehicle usage has been the status quo for nearly a century. Jaywalking laws—which require that pedestrians yield to vehicles by default and which didn’t exist until pro-automobile groups started promoting them in the 1920s—are now as ubiquitous as they are inconsistently enforced. Government response to snowstorms also provides a great case in point: Local and state governments bear responsibility for ensuring that roads and highways are passable for vehicles as quickly as possible. Individual property owners, meanwhile, are often required to shovel sidewalks expediently under threat of fines or summons, even in the most walkable metropolitan areas, such as New York City.

For generations, developers built suburban neighborhoods in response to consumer demand for single-family housing with abundant street parking. Building roads and highways became the most straightforward way to connect sprawling suburbs. Our communities are now so overwhelmingly designed for driving that people use cars for about 60 percent of trips that are less than a mile in length—trips that feasibly could be taken on foot if the system were designed to accommodate walkers safely.

Nonetheless, around 4.8 million people, or 3.4 percent of the working population, primarily walk or bicycle to work, and millions of other Americans regularly walk or bicycle to nearby restaurants or parks. Americans walked as means of transportation for nearly 41 billion trips—more than 10 percent of all trips, over the course of a year, according to the most recent National Household Travel Survey in 2009. The average number of nonautomobile trips per person will increase as denser, mixed-use developments become more commonplace, a trend that is expected to alleviate traffic issues around newer developments.

Policymakers, planners, and elected officials are now realizing that a car-dependent culture and suburbanization have created as many problems as benefits. Groups ranging from local developers to international nonprofits have made a concerted effort to improve the design of new developments and to retrofit existing ones. And New Urbanism—a set of planning principles based on building walkable communities through higher-density and mixed land use—is gaining popularity across the country.

For these changes to be effective, planners must think beyond housing and land use and include transportation in their community redevelopment efforts. Unfortunately, because roads often are designed with only cars in mind, walking and bicycling simply are not possible or are outright dangerous in many places. An increase in pedestrian and bicycle traffic absent improvements to things such as narrow sidewalks, limited crosswalks, and lack of bicycle lanes could make for an unpleasant and unsafe experience.

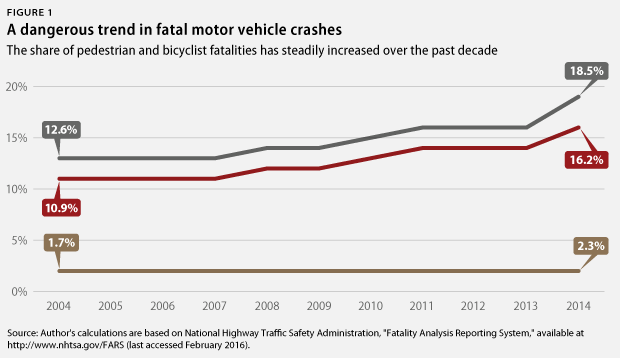

Safety is often touted as a paramount goal in transportation, and a quick glance at the number of fatalities from vehicle crashes might suggest that roads are getting safer: There were nearly 24 percent fewer traffic fatalities in 2014 than in 2004. However, the number of bicyclists and pedestrians killed during the same time span has been essentially constant. The upshot is that bicyclists and pedestrians are making up a larger share of total traffic fatalities as cars—which, after all, are 4,000-pound metal boxes—continually become safer for drivers and their passengers.

Fortunately, policymakers from the federal to the local level have indicated a desire to improve safety and mobility for alternative transportation modes. In 2015, Congress passed the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act, or FAST Act, which includes annual set-asides for transportation alternative programs that are set to increase from $890 million in 2016 to $1.02 billion in 2020. Each state receives a share of the funding specifically for local or regional projects that support nonmotorized transportation.

Another federal effort, the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Safer People, Safer Streets Initiative, directly addresses safety issues for pedestrians and bicyclists through new research and resources, as well as collaborations with mayors and local officials. President Barack Obama’s fiscal year 2017 budget includes a competitive grant program that would award almost $1.5 billion annually to fund proposals that improve mobility and encourage growth.

Some states and cities have been proactive, increasing funding for bicyclist and pedestrian infrastructure and adopting a set of policies, known as Complete Streets, to boost these modes. Formalized in the early 2000s, Complete Streets is a coalition of more than 850 agencies that focuses on planning, designing, and constructing roads that accommodate all users. Complete Streets emphasizes context; streets with different needs could look completely different while still achieving the same goal of making a street functional for everyone.

In recent years, cities of all sizes have embraced the concept of building Complete Streets: Nearly 58 percent of municipalities with Complete Streets policies are rural areas, towns, or small suburbs with fewer than 30,000 residents. Improvements in less populated areas, such as wider shoulders on high-speed roads or extra signage for crosswalks, can be simple but just as beneficial as in higher-density areas.

The most promising local development, however, may be the adoption of Vision Zero—a holistic proposal to eliminate all traffic deaths and injuries—in major cities across the country, including New York, Chicago, Seattle, and Austin. The initiative is based on the philosophy that any traffic-related casualty is unacceptable and emphasizes that surface transportation infrastructure should function in a way that prevents serious consequences as a result of human error. Complete Streets-like redesigns and regulations, education and public outreach, and targeted enforcement are common approaches to reduce traffic causalities. While eliminating all traffic-related deaths is a daunting challenge, most cities anticipate accomplishing their goals by 2030.

In order to achieve their safety and mobility goals, local leaders need strong support from state and federal partners. The federal government should provide additional funding and research targeted specifically toward nonmotorized transportation. States must ensure that cities include detailed and measurable goals for pedestrians and bicyclists in their long-range transportation plans. Only a strong commitment to better infrastructure, from all levels of government, will make it possible to ensure that streets across the country are safe and accommodating for all users regardless of mode.

Andrew Schwartz is a Research Associate on the Economic Policy team at the Center for American Progress.