Recent labor-market data bring some good news for a recovery that, until recently, seemed to be treading water. About 10.2 million jobs have been added to the U.S. economy, and the national unemployment rate has fallen from 10 percent to 5.5 percent—its lowest rate since the end of the Great Recession. Even the unemployment rate for historically vulnerable communities—such as African Americans and Latinos—has gained momentum, recovering to at or near prerecession levels. While these gains are laudable, broader economic indicators suggest that top-line numbers do not tell the full story of the labor market—one that details historically low growth in wages and considerable room for more employment growth.

Two factors account for the unusual amount of slack at this point in the labor-market expansion. First, it’s not exactly a secret that the Great Recession was much deeper than any other recession in recent memory. Second, employment growth in this recovery has been slow by historical standards. Due to this slack, real wage growth remains essentially stagnant. Continuing the trend of the past 30 years, corporate profit growth has been strong, while middle-class workers continue to grapple with the challenges of rising costs and slow wage growth.

The broader implications of these trends highlight the need for policies that promote inclusive prosperity as a means of achieving healthy economic growth. Here’s a look at some of the most important labor trends to watch this jobs day.

Many Americans who want jobs remain uncounted

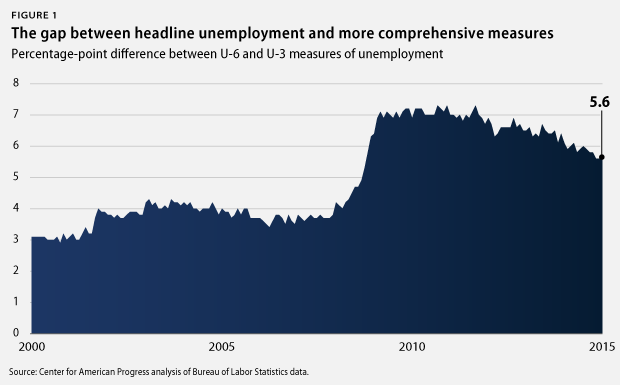

In February 2015, the headline unemployment rate—otherwise known as U-3—fell to 5.5 percent, its lowest rate since the end of the Great Recession. While this does mark significant progress in the recovery, it is important to remember that there are much broader measures of unemployment that paint a clearer picture of the employment situation. U-3, the typical measure, is pretty restrictive: It counts the percentage of people who are actively looking for work but cannot find it. Among the important features U-3 does not capture are the millions of people who want jobs but have given up looking or who would like full-time work but cannot find it in this economy. Perhaps the most comprehensive unemployment measure, called U-6, alleviates this problem by including marginally attached workers—those who have recently looked for work but are not currently looking—and those working part time but who would prefer full-time work. U-6 is always higher than U-3, but it has gotten a lot higher since the recession, and the gap has hardly changed over the past year.

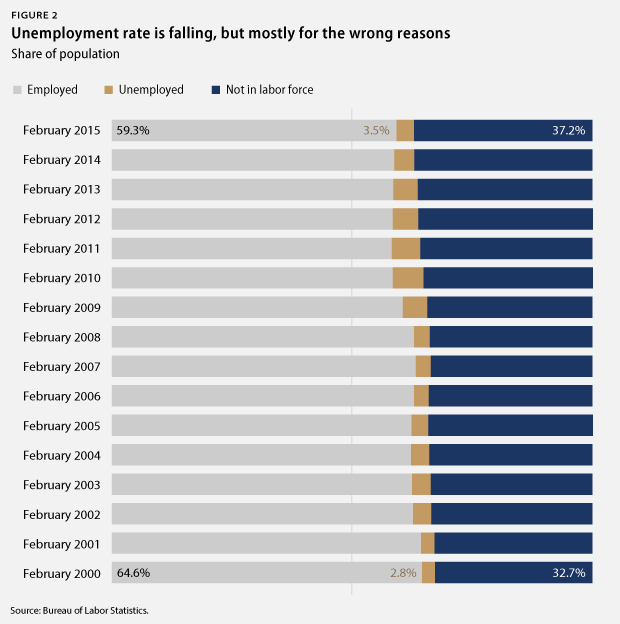

The labor-force participation rate also highlights these missing workers. When the economy is doing well, more people typically enter the labor market because there are more jobs available. So one should expect the labor-force participation rate to be increasing in the aftermath of the recession. It hasn’t been. Instead, it has declined steadily since the recession’s end and is as low today as it was in the late 1970s, when women entering the workforce became the norm. Even with the recent economic gains, labor-force participation is still stuck where it was at the end of 2013.

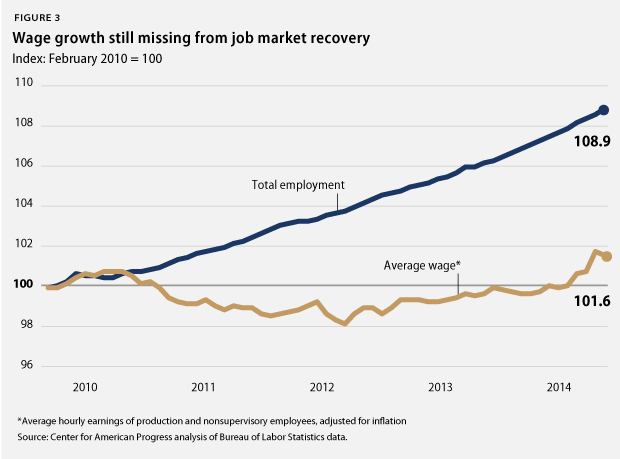

Americans are still waiting for a raise

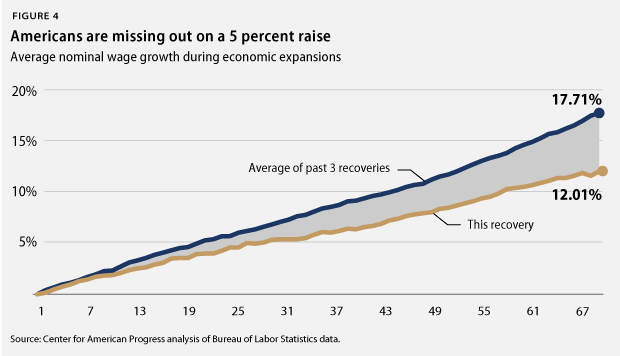

While employment growth has recently picked up steam, it has been incredibly slow by historical standards. Employment levels have grown at a rate of only 7.8 percent in this recovery, well below the historical average of 14.1 percent. And as depicted above, even broader measures of unemployment show that employment levels have considerable room for improvement. While employment growth remains sluggish at best, it continues to outpace the dismal rate of wage growth. Had wage growth kept up with the historical average, American workers would have seen a more than 5 percent raise since the beginning of the Great Recession.

Conclusion

As the Federal Reserve considers raising interest rates, it’s important to remember that even though the Great Recession officially ended in June 2009, many Americans are still suffering from its effects. Identifying the exact cause of the considerable slack in the labor market is a challenge—maybe it’s the underperformance of the housing sector or of Congress—but the slack in the economy is real. Beyond employment gains, wages had stalled before the recession and they have yet to accelerate in the recovery. On the jobs side, many people who want work are still missing from the labor force or are working fewer hours than they would like. These workers are the key to raising the nation’s potential economic output and future gross domestic product. It’s hard to predict what they will do as the economy picks up steam, but so far workers seem to be slowly coming off the sidelines, raising employment but tempering wage growth. However, this cannot happen forever, and as the expansion continues it is important for economic modeling to reflect responses to and changes in the real world.

Danielle Corley is a Special Assistant for the Economic Policy team at the Center for American Progress. Jackie Odum is a Research Assistant for the Economic Policy team at the Center. Michael Madowitz is an Economist at the Center.