The New Year’s Day agreement on tax rates, the American Taxpayer Relief Act, resulted in a modest amount of new revenue, coming mostly from an increase in taxes on the highest tax bracket—couples making more than $450,000 annually and singles making more than $400,000. But this revenue will not be nearly enough to achieve significant deficit reduction in a balanced way. More revenue is needed, and to raise it, Congress will have to confront the countless special tax breaks and loopholes in the tax code. This is true of the individual and corporate income tax, and it’s also true of the estate tax.

The estate tax—a tax on large amounts of wealth passed on to heirs—is permanently diminished in the wake of the new tax deal. The top estate-tax rate, though higher than it was last year, is still historically low. The deal also permanently extended a very large exemption that limits the tax to a tiny percentage of estates. But while making these parameters permanent, the law did not address the myriad estate-tax avoidance strategies employed by the richest Americans. It is therefore incumbent on Congress to put estate-tax loopholes on the table in future budget and tax reform negotiations. This column briefly explains the changes the estate tax has gone through over the years, and a number of ways to limit estate-tax avoidance.

The estate tax

For nearly a century the United States has imposed a tax on large estates to raise revenue and “preserve a measurable equality of opportunity,” according to one of its original proponents, former President Theodore Roosevelt. The estate tax is the most progressive part of our tax system because it is a tax on large transfers of wealth.

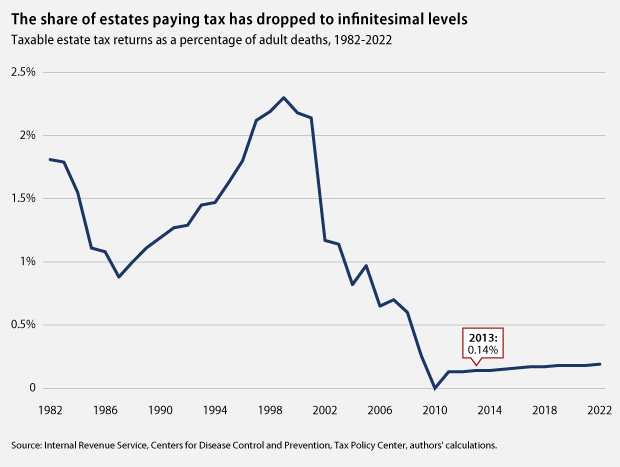

The estate tax has always been a small but consistent source of federal revenues, averaging about 1.5 percent of federal revenues between 1950 and 2000. But the Bush-era tax cuts enacted in 2001 dramatically reduced the estate tax to the point where it was entirely eliminated in 2010 before being brought back in greatly reduced form for 2011 and 2012 as part of the law that extended the Bush tax cuts.

The American Taxpayer Relief Act enacted earlier this month raised some revenue from changes to the estate tax compared to the tax’s 2011 and 2012 parameters—but not much. In his 2013 budget proposal, President Barack Obama proposed to tax estates valued at more than $3.5 million ($7 million for couples) up to 45 percent—which would have resulted in about $120 billion in new revenue over the next 10 years. Instead, the final deal set the exemption level at $5.25 million for 2013 ($10.5 million for couples), rising with inflation in future years, and set the top rate at 40 percent, which raises only $19 billion in new revenue over 10 years. (Compared to the pre-Bush estate tax that would have gone into effect had Congress done nothing, the deal lowers revenues by $369 billion over 10 years.)

As a result of these enacted policies, the estate tax applies to vanishingly few estates:

- The Tax Policy Center estimates that only 3,800 estates in the entire country—which is a miniscule 0.14 percent, or 1 in every 700 people who die—will pay any estate tax in 2013.

- While the top estate-tax rate is now 40 percent, the average taxable estate, because of the exemption and other special rules, will actually pay only 17 percent of the value of the estate. Even the richest estates—those worth more than $20 million—will only pay 19 percent on average, according to the Tax Policy Center estimates.

- While the estate tax has been frequently portrayed as a threat to small businesses and family farms, it is now clear that the estate tax is virtually irrelevant to small businesses and farms. The Tax Policy Center estimates show that only 20 estates in the entire country valued at less than $5 million, for which the bulk of the estate is comprised of a farm or a business, will owe any estate tax in 2013—and that tiny group will owe less than 5 percent on average. In fact, of the millions of farms and businesses in the country, only 120 large farm and business estates will owe any estate tax in 2013—and they will pay an average of less than 16 percent.

Given that the American Taxpayer Relief Act raised so little revenue from estate tax rates, it makes sense to now examine the estate tax base. In a recent op-ed, Harvard economist and CAP Distinguished Senior Fellow Lawrence Summers noted that the estate tax raises very little revenue compared to the vast wealth that is transferred to heirs every year:

A simple calculation shows that our estate tax system is broken. Assets that are passed to relatives or other personal relations are often badly misvalued relative to what they cost on an open market. The total wealth of American households is estimated at more than $60 trillion. It is heavily concentrated in very few hands. A conservative estimate given the lifespans of Americans would be that 2 percent ($1.2 trillion) is passed down each year, mostly from the very rich. Yet estate and gift taxes raise less than $12 billion, or just 1 percent of this figure each year.

The estate tax raises surprisingly little revenue in large part because of the various strategies that very wealthy families use to reduce the value of their estates for tax purposes. Some of these strategies are legitimate and clearly intended by Congress—such as the estate tax permitting a deduction for bequests to charity. But others push the bounds of the estate-tax rules.

The Obama administration has proposed several ways to reduce estate-tax avoidance that were estimated by the Treasury Department to raise a combined $24 billion over the next 10 years. (This estimate preceded the recent estate-tax changes.) These changes would not only raise revenue, but also would make our tax code more equitable. They are examined below.

Reform valuation discounts

Valuation discounts can be used to artificially reduce the value of one’s assets for estate- and gift-tax purposes. To give a quick example: Instead of bestowing one’s assets on heirs directly, a wealthy person can place his assets in a “Family Limited Partnership,” and then bequest units of the partnership to each of the heirs, with certain restrictions placed on the heirs’ ability to cash out or sell their respective interests. These restrictions allow the various interests to be valued separately, at less than the combined value of the Family Limited Partnership as a whole—the rationale being that no third party would pay full value for a partnership interest knowing about the restrictions. These kinds of discounts make some sense in other settings—for example, partnerships between unrelated people dealing at arm’s length with each other—but in a family setting, where the restrictions are set up for the very purpose of enabling the discounts, the logic is not as evident.

The Obama administration’s proposals would limit the use of valuation discounts involving family-controlled entities such as Family Limited Partnerships. Restrictions that lapse or can be removed by a family member would be ignored for purposes of valuing the assets transferred to heirs.

Impose consistent valuation rules for income-tax and estate-tax purposes

One’s “gross estate,” for estate-tax purposes, is based on the fair-market value of the person’s assets upon death. That same “fair-market value” standard determines the tax basis of the person inheriting the assets, which ultimately determines how much tax they’ll pay when they sell those assets. In general, putting a lower fair-market value on assets reduces the estate’s estate-tax bill, while putting a higher fair-market value on the same assets will reduce the heir’s future tax bills. Yet somehow, under existing law, estates can give one value and heirs can assume another value. The Obama administration would require that these two values match, with a reporting requirement on the estate that would allow the Internal Revenue Service to ensure that they do.

Reform Grantor Retained Annuity Trusts to limit estate-tax end-runs

Grantor Retained Annuity Trusts, or GRATs, are one of the exotic estate planning structures that allow wealthy people to transfer much of their assets to heirs tax-free. It’s especially beneficial for assets that are expected to increase in value. Case in point: A wealthy parent can establish a trust for the benefit of her children (a separate legal entity) and put her assets into it. The transfer is a gift, which can trigger a gift tax, but the gift tax applies to the value the parent puts on the assets now, not on what the value will be when she dies after it has appreciated in value.* (And with a Grantor Retained Annuity Trust, the gift-tax liability is reduced by the value of an annuity that the trust pays back to the parent.) If the assets appreciate in value while held by the trust, the appreciation escapes estate and gift taxes.

The Obama administration proposes to discourage the most aggressive uses of Grantor Retained Annuity Trusts by requiring a 10-year minimum term (ensuring some downside risk in the strategy because if the donor dies during the trust’s term, the strategy fails) and by requiring that the annuity not entirely zero out the gift tax.

Conclusion

These reforms are estimated to raise significant revenue, demonstrating why Congress can and should include revenues in any future budget deals. And these are hardly the only estate-tax avoidance strategies that deserve further scrutiny. Before Congress sacrifices needed public investments or puts programs that serve middle-class families at risk in the name of deficit reduction, it should ensure that the estate tax is actually paid by the few wealthy estates still subject to it.

Seth Hanlon is Director of Fiscal Reform and Sarah Ayres is a Research Associate at the Center for American Progress.

* The gift tax is intended to back up the estate tax by ensuring that lifetime gifts can’t be used to entirely avoid the estate tax. Yet it’s still often better for tax purposes to transfer assets during life and pay gift taxes on them than to transfer the same assets at death and have one’s estate pay estate taxes. This is because the size of one’s estate for estate-tax purposes is reduced-not only by the gift but also by the gift tax payment. In tax jargon, the gift-tax base is “tax exclusive” whereas the estate-tax base is “tax inclusive.”