Introduction and summary

Automatic Voter Registration (AVR) and preregistration are innovative policies that can increase voter registration and broaden civic engagement among Millennials and Generation Zs. Using the AVR and preregistration programs in Oregon and California as examples, along with new data from the 2018 midterm elections, this report illustrates the success these policies have had in registering eligible young people to vote and increasing their civic participation.

The programs noted above, which streamline the voter registration process, work as follows: AVR takes information already housed in state departments of motor vehicles (DMV) records, such as voters’ date of birth and address, and automatically sends it to the state elections office to register eligible citizens to vote. In states with both AVR and preregistration policies, 16- and 17-year-olds can preregister to vote when they interact with state agencies, including when applying for their driver’s license; their voter registration will become active automatically when they turn 18. Moreover, AVR and preregistration are particularly effective when they are combined. For instance, between January 2016 and August 2017, state DMVs submitted more than 1.8 million AVR transactions to the Oregon secretary of state for processing.1 By August 2017, Oregon’s AVR program—known as Oregon Motor Voter—registered more than 390,000 new potential voters.2 Of those citizens, more than 50 percent were under the age of 40 years old.3 The state’s preregistration program, which debuted in 2007 for 17-year-olds before expanding to include 16-year-olds in 2016, has seen more than 195,500 young Oregonians register to vote.4 More than 77,800 young people used AVR to preregister to vote and update their voter information.5 Of those who reached voting age during the 2018 midterms, more than 18,800 voted in that election.6

California implemented its AVR program—also called Motor Voter—in the spring of 2018. Despite some initial problems with implementation, an estimated 2.3 million Californians were registered or had their voter registration information updated through AVR.7 In addition, more than 221,700 16- and 17-year-olds have registered through California’s preregistration program, which was adopted in 2014.8 As was the case in Oregon, combining AVR with preregistration policies has been particularly effective in California. Of the 221,700 young, preregistered Californians, more than 77,600 preregistered or had their voter information updated through AVR.9 Of those preregistrants who reached voting age—50,800 individuals, or roughly 65 percent—turned out to vote in the 2018 midterms.10

The youth vote in the 2018 midterm elections

An incredible number of young people were energized and motivated to impact the outcome of the 2018 midterm elections. Through on-the-ground organizing for local candidates; taking to the streets with March for Our Lives rallies and in climate change protests; and turning out in high numbers at the polls, young voters made their voices heard. For the first time, young people witnessed the most diverse array of candidates running for office in American history, which in turn inspired them to become civically engaged like never before and demonstrate their power through the ballot.11 The work and dedication of young, civic-minded Americans from across the country helped elect the most representative and youngest Congress America has seen in decades.12 An estimated 31 percent of people between the ages of 18 and 29 participated in the 2018 midterm elections, amounting to a nearly 10 percentage points increase in turnout compared with the 2014 midterms.13 Early voting among 18- to 29-year-olds alone increased by 188 percent in 2018 compared with 2014.14 These numbers are stunning on their own but are particularly impressive considering young people are often blocked from voting due to convoluted voter registration processes, including arbitrary registration deadlines, confusing registration requirements, and logistical hoops that accompany registering to vote.15

It would not be a stretch to say that the 2018 midterms victories helped to restore, in no small part, young people’s faith in the democratic process. The increased presence of Millennials, women, LGBT people, and ethnic and religious groups on elected bodies can help young people feel more connected to their representatives and Congress as a whole.16 At the same time, however, still too many young people feel disenfranchised by a voter registration system that seems intent on suppressing their votes. A New Hampshire law that went into effect in 2018, for example, requires people registering within 30 days of an election to prove that they live in the ward or town in which they are trying to vote, which disproportionately disadvantages college students.17

Barriers in the voter registration process particularly affect young people partly because they are highly transient.18 For instance, studies show that Americans are more likely to relocate between the ages of 18 and 34 than at any other time in their lives.19 This is unsurprising given the number of young people attending college out of state as well as the frequency with which younger generations are changing jobs compared with older ones.20 Furthermore, as new voters, young people often lack the information and experience necessary to navigate the arcane and labyrinth-like systems for being added to the voter rolls. In some states, a college student may use their college dorm as an appropriate voter registration address. However, some universities lack individual mailboxes, making this process more complicated and daunting.21 Prior to the 2018 midterms, for example, students at Prairie View A&M University in Texas were instructed by election officials to use one of two addresses—the university address or the campus bookstore—on their voter registration applications because the university did not have individual mailboxes for students. However, students found out the addresses were in different precincts, with only one of the precincts on campus, which would reguire some students to fill out change-of-address forms on Election Day.22 Examples such as this show how voter registration information can be hard to find or altogether incorrect, forcing hundreds of students to reregister to vote due to conditions out of their control. Fortunately, there are solutions for making the process of registering to vote less burdensome.

Several states have begun recognizing the effectiveness of AVR and preregistration in improving voter registration and election participation for young Americans, partically when combined. Seven such states—California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Maryland, Oregon, Rhode Island, Washington—and Washington, D.C., have adopted AVR and preregistration for 16- and 17-years-old, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL).23

This report discusses the many benefits AVR and preregistration offer America’s youth and provides information on how these policies function on a procedural level. By way of illustration, this report examines the success of Oregon and California’s AVR and preregistration models and includes updated data from the 2018 midterm elections. As a result of these policies, each state—Oregon and California— saw surges in voter registration, particularly among young people. To recap:

- More than 390,000 Oregonians registered to vote through the AVR program. While the updated data on Oregon’s AVR registrants have not yet been finalized, 2017 data show that the program was key to registering more than 390,000 potential voters. Since 2007, more than 195,500 16- and 17-year-old Oregonians have preregistered to vote, with 77,800 preregistering through the state’s AVR program between 2016 and 2018. Of those who later turned 18 and became eligible to vote during the 2018 midterms elections, more than 18,800 cast a ballot and made their voices heard.

- 2.3 million Californians have registered to vote or had their voter registration information updated through the AVR program. In April 2018, California implemented AVR registration or updated the voter registration information of approxmiately 2.3 million people. California’s preregistration program had similar success. More than 221,700 16- and 17-year-olds have been preregistered to vote through California’s preregistration policy. Of those preregistrants, 77,600—or 35 percent—were preregistered to vote through California’s AVR program, with more than 50,800 of those who reached voting age participating in the 2018 midterms.

Given the successes of AVR and preregistration in states that have them, this report recommends both policies be adopted at the federal level. House Resolution 1 (H.R. 1), or the For the People Act, which Congress unveiled in January 2019, includes provisions that would require states to provide AVR for federal elections.24 States without these policies should take steps on their own to enact and implement them for the purposes of state and local elections. Efficient, safe, and secure pro-voter reforms such as AVR and preregistration increase total voter turnout, manage voter registration rosters effectively, and work to register eligible voters who have been marginalized by the current voter registration process.

Automatic Voter Registration

AVR is a policy that automatically registers eligible citizens to vote using information that state agencies already have on file.25 According to the NCSL, AVR policies have been adopted in 17 states—Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New Mexico, Nevada, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia—and Washington, D.C.26 Oregon was the first state to adopt AVR policies in 2015 and became the first state to implement the policy in 2016.27 California followed suit, becoming the second state to adopt AVR in 2015, and implemented the program in April 2018.28 In both states, eligible voters are automatically registered to vote through the DMV when a person interacts with the agency when applying for or renewing a driver’s license, in the process of changing their address, and more.29 Other states with AVR such as Rhode Island carry out AVR at other public agencies—in addition to the DMV—that regularly collect information necessary for determining voter eligibility such as age and citizenship.30

Registration is not compulsory, and all eligible potential registrants are given the opportunity to decline—or opt-out of—being registered through AVR, although the timing may differ depending on the specific program.31 In Oregon, for example, the DMV automatically transfers eligible potential registrants’ information to the secretary of state’s office. The DMV then sends a letter to the potential registrant informing them that they will be automatically registered to vote unless the letter is returned indicating their desire not to be registered to vote.32 In other words, under the Oregon model, an individual is given the opportunity to decline registration only after the agency interaction. Alternatively, in California, an eligible individual interacting with the DMV is given the opportunity to decline registration during their interaction with the DMV.33 In other words, an application to obtain or renew a driver’s license cannot be completed until the eligible citizen has been explicitly given the opportunity to decline voter registration.34

AVR improves the convenience and efficiency of registering to vote by ensuring that an individual’s voter registration follows them and is automatically updated if and when they move. This is particularly useful for highly transient young people.35 AVR also solves the hassle of mailing voter registration forms, which can be burdensome for young people.36

By electronically transferring data the state already has on file, AVR also improves the accuracy of voter registration lists by eliminating clerical errors that can occur through manual registration.37 In addition to improving accuracy, AVR policies protect the privacy of registrants and is a secure method of maintaining voter lists. For example, AVR laws often specify that data collected through the program may only be used for voter registration purposes. This safeguard often requires election officials to implement robust privacy and security policies, including for individuals with special confidentiality needs such as survivors of domestic violence.38 AVR programs may also require election officials to confirm a citizen’s eligibility before creating a completed voter registration application. Officials may be further directed to regularly update election records with a sophisticated multistate voter database, such as the Electronic Registration Information Center, which assists in keeping voter registration lists accurate and up to date.39

Finally, AVR can save jurisdictions money in the long term by eliminating the cost of paper registration forms as well a personnel costs. Take Oregon, for example: The Oregon State Elections Division spent roughly $530,000 over the past two years implementing its AVR program.40 Of that, approximately $330,000 was spent between 2016 and 2018 sending out letter notices to eligible individuals interacting with the DMV and providing them with the option to decline registration.41 There was also a one-time information technology cost of approximately $200,0000 to update the state’s voter registration system to accommodate automatic registration. Adding to this were predictable costs associated with having more registered voters in an all vote-by-mail state such as Oregon. There, the state is required to send all registered people a ballot prior to Election Day.42 Unsurprisingly, more registered voters means more ballots need to be printed and delivered, resulting in higher administrative costs. That said, some costs have been offset by savings derived from moving away from paper-based registration systems.43 For example, switching from paper-based registration to electronic registration has been shown to save jurisdictions money. In Maricopa County, Arizona, processing electronic voter registrations costs an average of just 3 cents per application, compared with 83 cents for processing paper applications.44

Ensuring that all voting eligible Americans are given the proper tools and opportunities to participate in the electoral process promotes effective governance that is more representative and better able to serve every constituent regardless of age or background. In Oregon, AVR was shown to be particularly helpful for those who are typically marginalized by the voter registration process such as young people, those living in rural areas, and people of color. While AVR helps every eligible citizen register to vote, those who typically benefit from AVR are more likely to live in low- and middle-income areas as well as lower-education areas.45

Again, AVR can increase voter turnout among young people due to their highly transient lifestyles, which makes registering to vote difficult due to arbitrary registration deadlines and differing voter laws in each state.46 Those living in rural areas, in middle- to low-income areas, and in areas with lower levels of educational attainment may lack access to crucial information on the ambiguous voter registration procedures and deadlines, which makes completing the forms more difficult. It may also be difficult for on-the-ground organizers to reach and register those individuals living in rural areas, particularly in states that do not offer online voter registration. A recent Center for American Progress report, “Increasing Voter Participation in America,” found that, based on Oregon’s experience, implementing AVR in all 50 states and Washington, D.C., could result in more than 22 million newly registered voters nationwide in the first year alone.47 Of those, 7.9 million additional voters could be expected to participate in elections.48

Preregistration

Young people of voting age were not the only youth involved in politics during the 2018 election cycle. Many Americans under 18-years-old also felt a desire and responsibility to engage politically on issues disproportionately affecting their generation, including gun violence, climate change, and growing student debt.49 The incredible activism that followed the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, is a perfect demonstration of the immense effect that people under the age of 18 have when it comes to everything from business interests to political debate around gun violence.50 Although they are not of voting age, these students are nonetheless demanding that politicians pay attention to their concerns and calls for change. These young people deserve an inclusive democracy that primes them to participate fully once they become of voting age. One effective way to ensure that young people are seamlessly integrated into the democratic process is to adopt policies providing for the preregistration of 16- and 17-year-olds.

Preregistration allows eligible 16- and 17-year-old citizens to preregister to vote so that once they turn 18, their voter registration is automatically activated.51 According to the NCSL, 14 states—including California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Rhode Island, Utah, and Washington—and Washington, D.C., allow 16- and 17-year-olds to preregister to vote.52 Oregon adopted preregistration in 2007 for 17-year-olds; the state expanded its preregistration program to include 16-year-olds in 2017.53 California adopted preregistration for 16- and 17-year-olds in 2014.54

The process for preregistering 16- and 17-year-old varies depending on the state. In California and Oregon, for instance, 16- and 17-year-olds may preregister online, by mail, or in person at county elections offices.55 Once they fill out the application, and their eligibility to preregister is confirmed, their voter information will be added to the state’s voter rolls in pending or preregistration status until they turn 18 and are eligible to vote.56

Preregistration benefits young people in several ways. First, being preregistered to vote means that the individual does not need to go through the hassle of registering to vote upon reaching voting age.57 As part of the preregistration process, their voter registration will simply go from a pending to activated status upon turning 18.

Second, the convenience that preregistration offers is important, considering that 18-year-olds may have more responsibilities and difficulty registering to vote compared with 16- or 17-year-olds. For example, 18-year-olds are often focused on applying for college or are in the process of moving away from home and starting college; they are also often juggling more demanding work and personal responsibilities, which leaves them little time to register to vote or navigate confusing registration rules.58 Moreover, 16- and 17-year-olds are more likely to be interacting with registration agencies such as the DMV, as that is typically the age at which people apply for driver’s licenses and other government services.

Finally, simply being introduced to the process of registering to vote is an important and effective way of getting young people excited about elections and civically engaged. An early introduction to the voter registration process can help demystify the electoral process and lead to less confusion when updating or renewing one’s voter registration in the future.59 Of course, once their voter registration is activated, young people will be more likely to receive information about political races and voting from campaigns and get-out-the-vote efforts that often rely on voter registration lists to conduct outreach.

A 2009 study of Florida’s preregistration program found that after the state implemented its program, young people who preregistered to vote were roughly 4.7 percent more likely to have participated in the 2008 elections, compared with those who registered upon turning 18.60 Compared with the 4.7 percent of all young people preregistered, African Americans who preregistered to vote were 5.2 percent more likely to participate in the 2008 elections than those who registered only after turning 18.61 Thus, although preregistration can help to open the voting process up to all young people, it can be particularly useful for narrowing participation gaps across demographic groups.

Today, many states have cultivated a number of best practices for preregistering young people. Successful outreach can be done in high schools in coordination with school administrators, teachers, and representatives from local county election boards.62 Election officials in some states have been known to visit high schools to hold classroom presentations and school-wide assemblies on voter registration and conduct voter preregistration drives.63 Other states have relied on information retrieved from school rosters to mail eligible students under the age of 18 informational forms about preregistration programs.64

Implementing a preregistration policy requires simple updates to government computer programs as well as some financial investments in outreach efforts to potential registrants.65 For example, computer software for state agencies and voter registration lists may need to be updated to manage and maintain more robust voter rolls, and officials would need to develop programs and procedures for automatically activating preregistrations once the individual turns 18 and becomes eligible to vote.66 Because outreach is critical for preregistration programs’ success, states must dedicate funding earmarked for notifying eligible 16- and 17-year-olds that preregistration is available to them and to inform preregistrants of their registration status, particularly once they turn 18. Resources are also required for conducting events and voter registration drives at schools and community centers, along with other places young people frequent. To lower the costs of outreach, state and local election offices can partner with local and national organizations such as Rock the Vote and the Alliance for Youth Action to help get young people excited about preregistering to vote.

Case studies: Oregon and California

The following analysis examines Oregon and California’s AVR and preregistration programs using recent data provided by their respective secretaries of state. The two states were selected for this analysis because both have implemented AVR and preregistration for which the authors were able to obtain data.

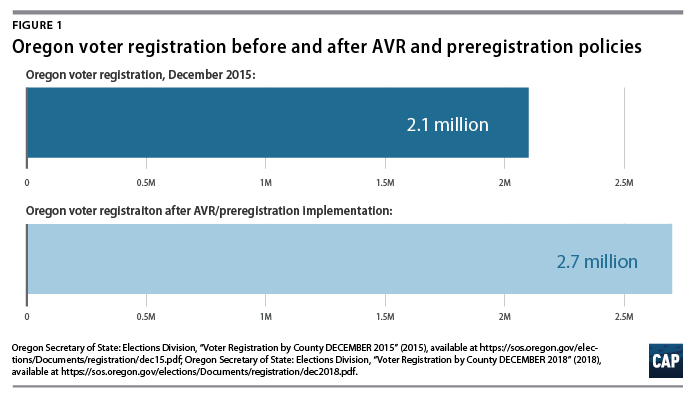

As noted above, Oregon was the first state in the nation to implement AVR in 2016—just in time for that year’s contentious presidential election.67 While the updated data on Oregon’s AVR registrants have not been finalized, 2017 data showed that Oregon’s AVR program registered more than 390,000 potential voters since it was first implemented.68 Additionally, more than 195,500 of 16- and 17-year-olds have preregistered to vote through the state’s preregistration policy since its implementation in 2007.69 These programs have been successful individually but are particularly beneficial for young people when they are combined. In Oregon, for instance, 77,800 16- and 17-year-olds were preregistered through the state’s AVR program between 2016 and 2018. Of those who became eligible to vote during the 2018 midterms elections, more than 18,800 cast a ballot.70 In other words, nearly one-quarter of 16- and 17-year-olds who preregistered through Oregon’s AVR program and turned 18 on or before Election Day participated in the 2018 midterm elections. This number is expected to grow in future elections, when the roughly 27,000 young people who preregistered through AVR and whose registration statuses are currently pending reach voting age in 2020.71

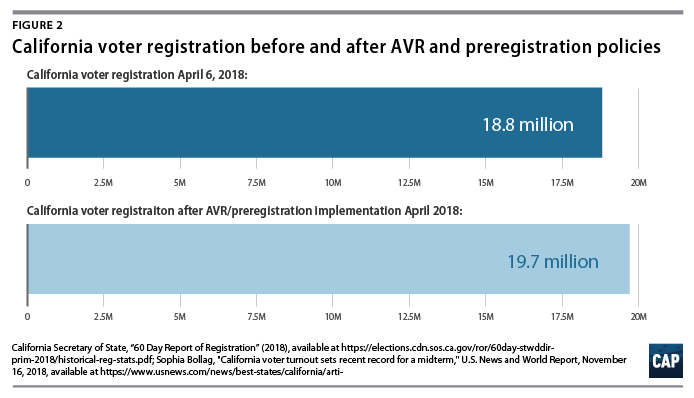

As noted previously, California was the second state to adopt AVR in October 2015 and implemented the program on April 23, 2018.72 The state initially experienced some difficulties implementing the program, including registration errors at DMVs.73 To prevent further problems, the secretary of state’s office intervened in October 2018 and demanded additional review of potential registrant information to ensure its accuracy.74 Gov. Jerry Brown (D) also ordered a performance audit of state DMVs’ implementation of AVR.75 California’s experience highlights the importance of dedicating sufficient resources and conducting robust training for election officials and others responsible for executing new programs, as well as exercising due diligence when implementing statewide policies. In spite of these obstacles, however, since AVR was implemented in the state, 2.3 million Californians have registered to vote or had their registration information updated through the program. Within just the first few months of its implementation, California’s AVR program helped to update the addresses of 120,000 voter registrants.76

California’s preregistration program has also seen success. For example, more than 221,700 16- and 17-year-olds have been preregistered to vote through the state’s program.77 And more than 88,500 of those who preregistered and whose registration is still pending will reach voting age in 2020.78 But California’s dual preregistration-AVR program was the real star. For instance, 77,600—or 35 percent—of preregistrants were preregistered to vote through California’s AVR program.79 Of those, more than 50,800 who turned 18 on or before Election Day participated in the 2018 midterm elections.80 Put simply, nearly 65.5 percent of young people who preregistered to vote through California’s AVR program and became age eligible to vote participated in the midterms.

Recommendations

Joint AVR and preregistration programs are an incredible tool for voters across all demographics and regions of the United States, but it is essential for young people who are systematically disenfranchised by traditional voter registration processes. Moreover, in the current political climate, young people play a crucial role in determining and driving policy priorities, as well as affecting election outcomes.

To ensure that young people are able to register to vote and participate fully in America’s elections, the authors recommend that:

Lawmakers and officials:

- Pass AVR and preregistration for 16- and 17-year-olds at the state and federal levels.

- Expand existing AVR programs beyond DMVs by designating other state and government entities as source agencies, including social service agencies, universities, and departments of corrections, to ensure diverse outreach to all eligible voters.

- Adopt and implement preregistration programs. State officials should require and help facilitate coordination between high schools and local election boards for the purposes of informing young people about the availability of preregistration and encouraging participation through presentations and preregistration drives at school assemblies, youth sports events, among other school-related events.

- Coordinate with local organizations advocating for pro-voter reforms at the state and local levels when implementing AVR and preregistration programs. Common Cause, the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon, the Bus Project, the Urban League of Portland, student groups, and disability rights groups all played important roles in state adoption of AVR policies across the country.

Individuals:

- Check their secretary of state’s website to see whether policies such as AVR and preregistration are available. In addition, check the current status of your voter registration situation if you are 18-years-old or older and eligible to vote.

Additionally, jurisdictions should adopt other pro-voter policies that help young people vote such as same-day voter registration with Election Day registration (EDR) and early voting.81 According to the NCSL, as of January 2019, 17 states and Washington, D.C., have implemented EDR: California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois, Michigan, Maryland, Connecticut, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. While it is difficult to measure the effects these policies have had on voter turnout, there is strong evidence that suggests they increase voter participation, particularly immediately after implementation.82

Conclusion

To maintain America as a functioning and vibrant democracy, voter registration must be easily accessible and understood, particularly for young people. Millennials and Generation Z represent the largest electoral bloc in the nation; therefore, it is necessary that legislators take note of the current demands of this growing political body and provide young people with access to tools and resources to fully realize their power at the polls.83

It is crucial that young people are energized around voting, are civically engaged, and can cast their ballot once they become eligible to vote. Oregon and California show that AVR and preregistration are efficient, secure, and inclusive policies that can increase voter registration among traditionally marginalized groups, raise voter turnout, and encourage young people to participate in civic engagement well before they cast a ballot.

About the authors

Anisha Singh is the former senior organizing director at Generation Progress, the youth-engagement arm of the Center for American Progress.

Brittney Souza is an organizing associate with Generation Progress.

Danielle Root is the voting right manager for Democracy and Government at the Center.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Liz Kennedy and Kiara Richardson for their contributions to this report.