Once a decade, every state redraws its electoral districts, determining which people will be represented by each politician. In many states, this means that politicians gather behind computer screens to figure out how they can manipulate the lines to box out their competition and maximize the power of their political party. While an increasing number of states employ independent commissions to draw district lines, the large majority still lack safeguards to prevent partisan favoritism in the redistricting process—also known as partisan gerrymandering.

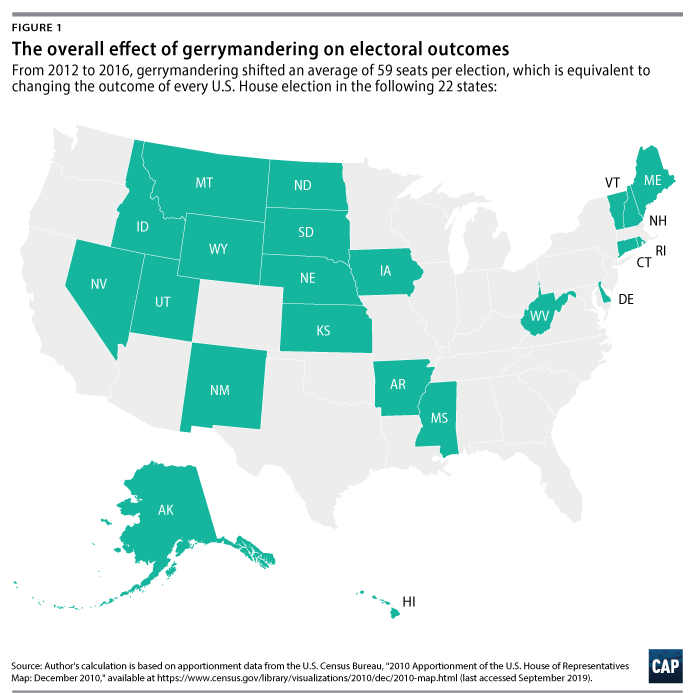

It has been almost a decade since the 2010 cycle of redistricting, and the country is still reckoning with the impact. Last May, the Center for American Progress published a report that found that unfairly drawn congressional districts shifted, on average, a whopping 59 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives during the 2012, 2014, and 2016 elections. That means that every other November, 59 politicians that would not have been elected based on statewide voter support for their party won anyway because the lines were drawn in their favor—often by their allies in the Republican or Democratic Party.

To help put this number in perspective, a shift of 59 seats is slightly more than the total number of seats apportioned to the 22 smallest states by population. It is also more than the number of representatives for America’s largest state, California, which has 53 House members representing a population of nearly 40 million people.

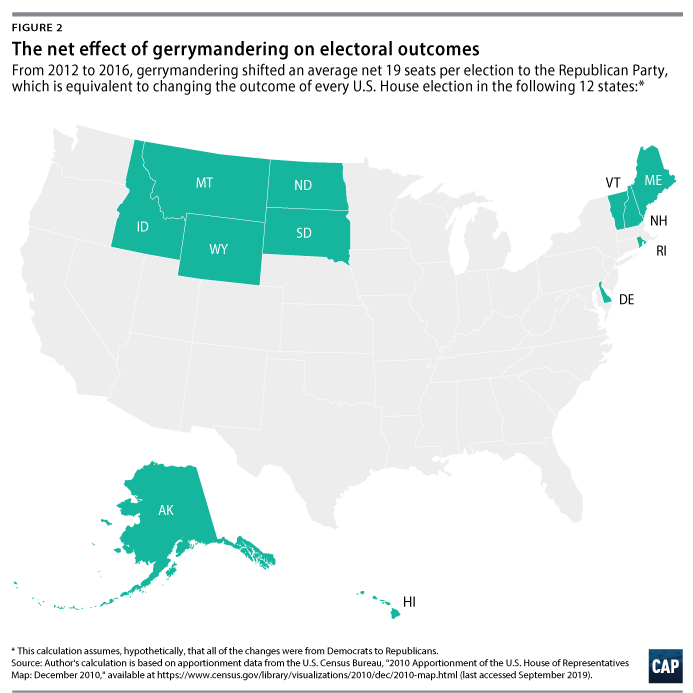

Of the 59 seats that were shifted per election due to partisan gerrymandering, 20 shifted in favor of Democrats while 39 shifted in favor of Republicans. This means that from 2012 to 2016, the net two-party impact amounted to an average gain of 19 Republican seats per election, which is still more than the number of seats in a dozen U.S. states.

Of the 59 seats that were shifted per election due to partisan gerrymandering, 20 shifted in favor of Democrats while 39 shifted in favor of Republicans. This means that from 2012 to 2016, the net two-party impact amounted to an average gain of 19 Republican seats per election, which is still more than the number of seats in a dozen U.S. states.

One can also look at the effects of gerrymandering in terms of population. The average congressional district has a population of slightly more than 700,000, which means that a total shift of 59 seats is equivalent to representation for approximately 42 million Americans. Moreover, the 19 net seats Republicans gained are equivalent to representation for about 13.5 million Americans.

The inescapable conclusion is that gerrymandering is effectively disenfranchising millions of Americans. This should be considered a critical situation. If the voters of even one of the states above were excluded from the count, there would be a national outcry; with a net impact equivalent to the exclusion of 12 states, the urgent need to address gerrymandering should be clear.

Fortunately, the solution is simple: require each state to draw districts that accurately reflect the political views of the American people. Such “voter-determined districts” are based on the principle that however the voters in a state are divided between the major parties, the districts should be divided in the same way. Accordingly, in a state in which voters are split 50-50 between Republicans and Democrats, the representatives would also be split 50-50.

Depending on the number of districts, and where people live, it may not always be possible to perfectly align the population and its representation. But the purpose of voter-determined districts is to align them as closely as possible. And thanks to map-drawing software, map drawers are better able to do that now than ever before. States simply have to take the tools that have been employed in recent decades to gerrymander and use them to draw fair districts instead. However, to ensure that the process is not manipulated to the benefit of a particular political party, the maps should be drawn by an independent commission, not elected officials.

The redistricting process should also prioritize ensuring fair representation for communities of color, who continue to be drastically underrepresented in Congress and even more underrepresented in state legislatures. Moreover, states should draw districts that are reasonably competitive, so that when voters change their minds, they can also change their representatives.

That’s democracy—elected officials who represent and are accountable to the people. The numbers show that representation in the United States is far from fair, but with straightforward policy changes, citizens can have maps that are fair.

Alex Tausanovitch is the director of Campaign Finance and Electoral Reform at the Center for American Progress.