This issue brief contains a correction.

Federal public safety and criminal justice grants are in dire need of modernization in the United States. The primary statutes funding these grants were enacted in the mid-1990s during the height of the “tough-on-crime” era that espoused crime suppression through mass incarceration.1 The U.S. Congress and the executive branch have not comprehensively reviewed the goals of these grants in more than 25 years, during which time academics have widely documented the failures of tough-on-crime approaches. As the Vera Institute of Justice has noted, “Research consistently shows that higher incarceration rates are not associated with lower violent crime rates.”2 The overreliance on incarceration has instead created undue harm for communities of color, particularly Black Americans, who have been unjustly targeted by the justice system. 3

Today, the movement to end mass incarceration and police violence is gaining steam. Communities are calling for a smaller justice system that is no longer the primary response to many social issues, from behavioral health disorders to homelessness to school discipline. These are not new priorities; rather, national public awareness has started to catch up to what many communities have been advocating for years. Yet federal funding mechanisms are still stuck in the 1990s. Instead of pushing jurisdictions toward justice reform, the largest available justice-related grants incentivize deference to law enforcement and criminal justice agencies, which have historically perpetuated approaches that drive up arrest and incarceration rates. Dedicated funding streams for reform-minded strategies are much smaller and are generally awarded on a competitive basis, thereby limiting the number of jurisdictions that can use federal funds to promote change.

Grants administered by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) need wholesale changes in order to accelerate a much-needed transformation of the country’s criminal justice and public safety systems. Not only should the DOJ strengthen requirements for grantees, but lawmakers must also reconstruct the very purpose of DOJ grants to ensure that federal dollars are used to support evidence-based strategies rooted in principles of fairness and justice. This issue brief examines the problems with the current structures of DOJ grants and lays out a new framework that modernizes the federal government’s approach to funding criminal justice reform and public safety.

Problems with the structure of federal grants

Federal grants can be a crucial instrument to influence criminal justice and public safety systems nationwide. Each year, the DOJ distributes more than $5 billion in federal grants annually to state and local governments, research institutions, and nonprofit organizations.4 DOJ grant sums pale in comparison to the aggregated budgets of justice systems across the country, which are primarily funded through state and local governments. Yet federal grants can be catalysts for change when utilized effectively and in concert with other levers, such as the federal government’s authority to investigate state and local entities and officials for unconstitutional conduct, as well as the power of the bully pulpit, which provides a platform for the president and the U.S. attorney general to highlight policy priorities or systemic problems.

Unfortunately, when it comes to funding through grants, the federal government’s approach has been anything but deliberate or strategic. The leading public safety grants, such as the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grants (JAG), give maximum flexibility to recipient jurisdictions to use the funds how they see fit with few meaningful constraints. JAG is a formula grant, meaning that all states and certain localities are entitled to receive these funds. The amount awarded to each jurisdiction is determined by population and violent crime rate.5 As the Center for American Progress found in a 2019 report, nearly 60 percent of state-level JAG funds were used to support law enforcement and corrections functions, significantly outweighing investments in prevention efforts or justice system reform.6 Similarly, the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) Hiring program provides funding for police departments to hire more officers but includes few limitations on the functions those officers carry out or requirements for the police department to engage in community policing.7

Part of the problem may be that DOJ formula grants are too small, especially compared with the state and local assistance programs of other federal agencies. Over the past 25 years, Congress has reduced DOJ grant funding significantly, especially formula grants. Lower grant funding levels prevent state and local governments from enacting large-scale systems reforms. Instead, jurisdictions are incentivized to supplement existing programs and structures, as changing entrenched systems requires significantly more resources than maintaining the status quo.

The federal government has, in some instances, leveraged legislative and executive power to pursue reform efforts. For example, grants under the Second Chance Act provide services for formerly incarcerated people, and grants through the Smart Policing Initiative promote data-driven policing practices.8 Whereas large formula grants can target broad swaths of the justice system for structural change, these grants have lower dollar amounts and are narrower in scope. Moreover, jurisdictions must compete for a small number of awards, limiting the DOJ’s potential to incentivize reform. The pool of applicants for competitive grants is also self-selecting, given that only jurisdictions that are committed to the goals of the program will apply. Further limiting the pool of applicants is that competitive grants favor those that are well organized and have sufficient resources to assemble compelling applications. While it would be advantageous to integrate smaller grants into a broader transformational plan, current grantmaking structures inhibit this type of coordination.

Finally, it is important to improve grant administration at the state and federal levels. The Office of Justice Programs (OJP), the primary funding component within the DOJ, has an important role to play in strengthening coordination and oversight of federal investments. Lack of coordination at the federal level translates into insufficient coordination on the ground. For example, grantees from the same jurisdiction may be receiving funds for complementary projects from various federal sources but remain unaware of the other agency’s efforts. OJP can amplify its impact by strengthening oversight of fund usage, especially for formula grants, and focusing on meaningful outcomes. States likewise should play a greater role in setting a cohesive statewide agenda by coordinating the use of funds across localities, guided by input from community stakeholders—especially communities of color, which have been disproportionately targeted by the justice system and excluded from shaping public policy for generations.9

Proposal to reform the DOJ’s grantmaking strategy

The federal government is uniquely situated to advance systemic reforms for state and local-level criminal justice and public safety practice. Maximizing federal impact, however, will require an overhaul of the DOJ’s grantmaking strategy, with a focus on realigning incentives and promoting structural change. While a large influx of new appropriations would be beneficial, lawmakers can achieve substantial change by consolidating and complementing existing funding streams with a limited amount of new funding, as long as they rebuild the underlying purposes and processes of DOJ grants.

With these goals in mind, the Center for American Progress has identified four foundational elements that can serve as a framework for revamping the DOJ’s grant portfolio:

- Congress should consolidate existing grants and add new funding to create large formula grants that accelerate change instead of pursuing piecemeal strategies that support narrow programmatic goals.

- Each formula grant should have a set of purpose areas that are specific, defined, and contribute to the goals of ending mass incarceration, promoting comprehensive public health and safety, and ensuring accountability in policing.

- Each formula grant should specify prerequisites that the applicant must meet before receiving the funds, as well as outline ongoing requirements after funding has been awarded.

- The administration of the formula grants—at both the federal and state levels—must be improved to foster transparency around what activities are supported by federal dollars.

Create new formula grants

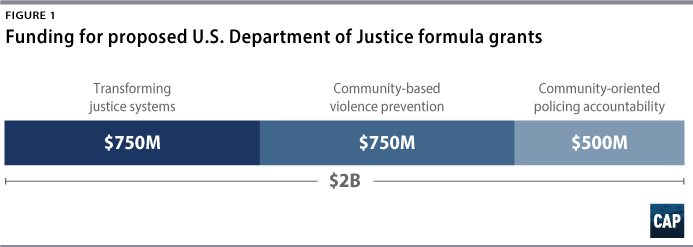

To maximize the impact of federal investments, the DOJ should merge existing disparate funding streams to form several large-scale formula grants, each structured around a specific goal. One formula grant should be dedicated to accelerating the transformation of the justice system, centered on ending mass incarceration and improving the fairness of the system. Such a grant might fund efforts to end cash bail and reduce unnecessary pretrial detention, expand access to quality indigent defense, improve prosecutorial oversight and accountability, reexamine sentencing and correctional practices, and promote successful reentry for the formerly incarcerated.

A second formula grant should replace existing DOJ grants for policing, including the COPS Hiring program and parts of JAG, to become the new primary funding vehicle for reforming policing practices and accountability systems. The new formula funds should be structured around the goals of strengthening accountability for law enforcement, advancing police reform, and enhancing transparency in policing. While existing policing grants are used primarily to fund hiring, equipment, and other basic administrative functions that perpetuate existing structures, these new formula grants would be designed to incentivize change among law enforcement agencies.

Finally, the DOJ can establish a third formula grant aimed at building capacity for community-based solutions to crime, violence, and other safety concerns. By establishing this grant, the federal government could make an unprecedented and long-awaited investment in community priorities such as violence prevention and intervention, civilian first responders, restorative justice initiatives, and other community-driven priorities. Importantly, such a grant could provide much-needed funding for civilian offices of neighborhood safety within local governments, which provide the infrastructure and operational support for such interventions to succeed.10

New formula grants should provide direct grant awards to states, with a requirement for states to redistribute a significant portion of funds to localities. Importantly, localities would still receive funding under all formula grants, but their awards would come from the state rather than directly from the federal government. To facilitate large-scale reforms, the DOJ can empower states to set a cohesive strategy for allocating funding across localities. This framework is intended to address fragmentation caused by a current statutory requirement that JAG funds be split 60-40 between states and localities, resulting in more than 1,000 grant awards disbursed per year. The current piecemeal funding approach limits the cumulative impact of JAG, particularly considering that many grantees receive small-dollar awards. According to a CAP analysis, the DOJ awarded more than 450 JAGs valued at less than $25,000 in FY 2016 , accounting for roughly 44 percent of JAG funds that year.11

The new framework will strengthen impact on the ground by allowing states to target larger amounts of funding toward localities with the greatest need, rather than parceling available funds into smaller slices based on a congressionally mandated formula that may not capture the full picture. Local JAG allocations, for instance, are determined by the jurisdiction’s share of statewide violent crime, a statistic that provides a limited picture of justice system needs.12 Rural counties and other small municipalities record considerably fewer violent crimes than cities yet struggle with disproportionately high rates of jail incarceration, often due to a scarcity of resources.13 Because resource allocation tends to favor more populous jurisdictions, rural areas may be forced to rely on jails in the absence of robust mental health and pretrial services, diversion programming, or other alternatives to incarceration.14 By providing states with flexibility to target subgrants, this framework will mitigate resource allocation concerns perpetuated by existing formula grants.

Define specific purpose areas

It is vitally important that new formula grants detail purpose areas and goals with sufficient specificity to ensure that federal funds are used to support evidence-based approaches to reforming state and local criminal justice and public safety infrastructure. A key drawback of current formula grants such as JAG is the lack of specificity in the purpose areas. JAG lists eight general areas for authorized activities: (1) law enforcement programs; (2) prosecution and court programs, including indigent defense; (3) prevention and education programs; (4) corrections, community corrections, and reentry programs; (5) drug treatment and enforcement programs; (6) planning, evaluation, and technology improvement programs; (7) crime victim and witness programs other than compensation; and (8) mental health programs and services. Beyond these headings, there is virtually no guidance for how JAG dollars can and should be spent. Jurisdictions can and have used JAG to advance evidence-based approaches to public safety and justice reform, but providing maximum flexibility to states more often results in the perpetuation of existing structures over systemic change.

Lack of specificity has affected competitive grant programs as well, including the COPS Hiring program, which provides funding for police departments to hire new officers or rehire officers who were laid off due to budget cuts.15 Though the program was created with the goal of promoting community-oriented policing, it has offered sparse guidance on what types of activities constitute “community-oriented policing.” Instead, the DOJ left it to the discretion of local police agencies, many of which used the grants to support militarized, zero-tolerance policing models.16 The issues with these grants persist, despite efforts during the Obama administration to reform the program.

The new formula grants should therefore include specific descriptions of each purpose area to ensure that federal dollars are used to implement evidence-based strategies that are directly aligned with program goals. For example, a formula grant focused on transforming justice systems could include a purpose area focused on pretrial justice. Under such a purpose area, grantees might be permitted to use funds to end the use of cash bail, improve notification systems to alert people of upcoming court dates, or ensure that a hearing is conducted when a person’s pretrial status is being considered. In turn, community-based public safety grants could provide funding for civilian offices of neighborhood safety and violence interrupters, rather than unproven prevention strategies such as public awareness campaigns.

Likewise, the grants for policing reform could be used to implement requirements and trainings for officers to de-escalate situations, as well as create a national database that tracks officer misconduct that police departments must check before hiring an officer. Congress could also place restrictions on the use of funds to buy equipment or hire new officers. Should Congress prioritize the recruitment and retention of a diverse police workforce, they could include specific requirements for this process that currently do not exist, such as limiting the hiring of officers to those who meet specific educational requirements and have established residency within the agency’s jurisdiction and requiring preapproval from the DOJ that the agency has met certain police accountability thresholds before allowing funds to be used for this purpose.

Strengthen grant requirements

DOJ grants must also include requirements aimed at priorities such as strengthening community engagement and data collection procedures. It is imperative, for example, that grant recipients are informed by a wide range of stakeholders, not just law enforcement, prosecutors, or other justice system practitioners. To do so, states could convene a council of diverse stakeholders to guide the spending strategy for new formula grants. With oversight and management from the state government, the councils could develop a cohesive and coordinated approach for grant fund usage, including plans for subgrant allocation to localities and other eligible entities. Councils would comprise representatives from state and local governments, criminal justice and public safety agencies, research and academic institutions, public health and social service providers, and nonprofit organizations. Specifically, organizations serving formerly incarcerated individuals and the communities most affected by overcriminalization should play a key role in guiding the state’s vision for the grants. States could also add a clause that caps the percentage of council membership coming from government or justice system agencies.

In an effort to strengthen accountability, the DOJ should condition grant eligibility on requirements for collecting data. For example, in order to remain eligible for formula grants focused on police accountability and justice system transformation, states might need to demonstrate compliance with the Death in Custody Reporting Act, which requires states to regularly report information to the DOJ about any deaths that occur during the process of arresting, detaining, or incarcerating an individual.17 Likewise, eligibility requirements might include the enactment of a set of base-level policy reforms. In the case of a grant focused on police accountability, grantees could be required to revise use-of-force standards, ban practices such as no-knock warrants and chokeholds, and provide training on racial bias and duty to intervene.

Such requirements are relatively uncommon among existing federal grants. Currently, a state may lose a portion of its JAG allocation for failure to comply with either the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act or the Prison Rape Elimination Act, although they would retain eligibility for the grant. Few grant programs tie funding eligibility directly to evidence-based policy or data-related requirements, which is a missed opportunity to infuse data-driven practices into state and local-level justice systems. By condensing disparate funding streams into larger grants with stronger requirements, the DOJ can maximize the potential impact of federal dollars.

Improve transparency and grant administration

Overhauling the DOJ’s grantmaking strategy is also an opportunity to strengthen the oversight and administration of grants, a persistent problem for the agency. The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) within the DOJ consistently ranks grants management among the top challenges facing the department, in part due to “the sheer volume of recipients and money involved.”18 The DOJ can significantly cut down on the volume of grant awards made each year by combining numerous funding streams into several larger formula grants for states. Under such a structure, federal grant managers can work directly with a state government to monitor grant spending and performance, rather than having to track countless smaller grants awarded to disparate localities and nonprofits nationwide. As part of this effort, the DOJ would need to establish procedures for rigorous oversight of federal funds flowing from states to localities and nonprofits, especially given that the agency has periodically struggled to keep tabs on subgrants.19

In a 2013 analysis of the Byrne JAG program, the Brennan Center for Justice found that the DOJ’s efforts to monitor subgrants were hampered by existing reporting mechanisms, which allowed grantees to choose how they would prefer to report information to the agency. According to the report, “Some states report back on behalf of subrecipients and some do not,” with states not always aware of the information submitted by their subgrantees.20 Even among direct grant recipients, reporting is often spotty: As many as 30 percent of JAG recipients do not submit regular reports to the DOJ, and the Byrne JAG statute largely prevents the agency from withholding grant funds to mandate compliance.21 Establishing strong and uniform requirements for states to report on subgrant activity would also reduce the risk of duplicative grant funding, an issue identified by auditors from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) in 2012.22 The GAO found shortcomings in existing procedures for reporting and utilizing information on subgrant disbursement, creating the risk that a subgrantee could receive funds from multiple DOJ grant programs to support the same or similar activities.23 If states were required to provide the agency with a clearer view of the subgrant landscape, the DOJ could more effectively protect against duplication of funding.

Effective grants management is further complicated by the fact that many existing programs have “objectives that are often hard to quantify and results that are not adequately measured,” according to the OIG.24 Thus, efforts to overhaul the DOJ’s grantmaking strategy should prioritize the establishment of clear program goals that are linked to relevant metrics of progress. For the new formula grants described above, each purpose area should have distinct performance measures on which grantees and subgrantees must report. JAG recipients, for example, are currently required to answer issue-area specific questions regarding grant activities. Though performance measures were revised in 2014 to improve accountability, these measures should be further refined to better reflect the goals of new grants.25 For instance, law enforcement grantees are currently required to indicate only whether use-of-force incidents increased or decreased during the grant period but are not asked to provide the total number of incidents, preventing the DOJ from tracking meaningful progress.26 Nor does the current questionnaire request data on racial and ethnic disparities in policing, another important metric for reducing inequities in the justice system.

The DOJ should also increase transparency around grant activities and performance. Currently, the agency provides extremely limited data on how grantees and subgrantees spend federal dollars, particularly when it comes to formula grants such as JAG. Analyses of state-level JAG spending are made available through the National Criminal Justice Association, a membership organization that works directly with states to collect JAG spending data, but there is virtually no information widely available on local-level JAG spending and outcomes.27 The DOJ should both publish this information on its own website and require grantees to do the same.

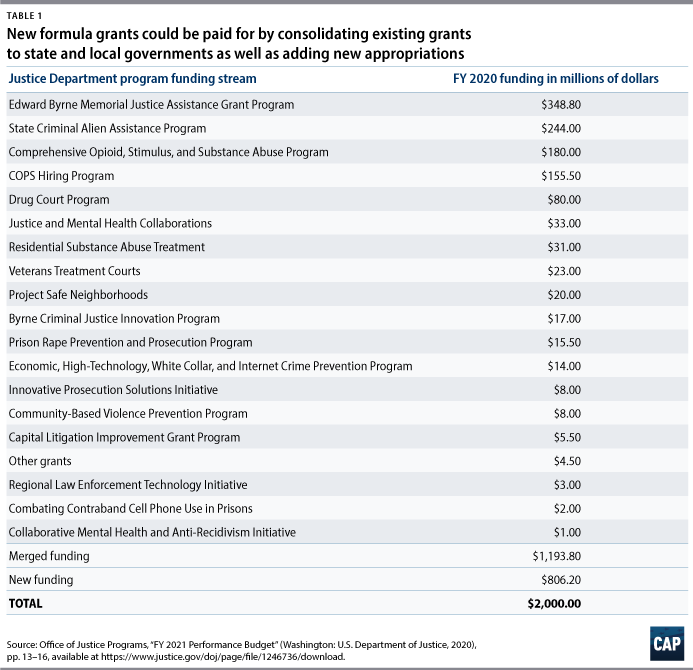

The following table provides an example of how to pay for the new formula grants proposed in this report. While Congress could choose to appropriate new funding outright to cover the entire cost of the proposal, this proposal consolidates existing grants to state and local governments—many of which serve purposes that could be absorbed into the grants—as well as adds new appropriations.

Conclusion

Over the past 25 years, America’s understanding of criminal justice and public safety policy has evolved substantially, yet the DOJ’s grantmaking structure has remained largely untouched. A modernization of the DOJ’s funding approach is long overdue. To maximize the impact of federal dollars, lawmakers should create large formula grants with clear purpose areas and requirements structured around the goals of ending mass incarceration, advancing comprehensive community-based public health and safety, and strengthening police accountability. By consolidating existing grant programs into larger formula grants, the DOJ can simultaneously improve its oversight of federal funds and expand its reach among jurisdictions that might otherwise be slow to adopt evidence-based reforms. The DOJ’s $5 billion annual grants budget presents a powerful tool for accelerating the adoption of best practices within state and local justice systems, and it is time for the agency to make the most of this opportunity.

Mike Crowley is a criminal justice reform advocate and consultant. He is a former senior fellow with the Brennan Center for Justice and former senior policy analyst with the White House Office of Management and Budget. Betsy Pearl is an associate director for Criminal Justice Reform at the Center for American Progress.

The authors would like to acknowledge Ed Chung for his significant contributions to the development and authorship of this issue brief.

* Correction, October 19, 2020: This appendix has been corrected to include the Death in Custody Reporting Act.

Appendix: Proposal for new formula grants to accelerate criminal justice transformation and community-based safety

1. Transforming justice systems formula grant

Grants to states, U.S. territories, and tribal governments to accelerate the transformation of the criminal justice system, end mass incarceration, and improve fairness within the justice system

Funding level: $750 million

Purpose areas

- Pretrial reform. Grants to safely reduce rates of pretrial detention. Funds may be used to end reliance on money bail, provide access to counsel at first appearance, strengthen pretrial services and notification systems, expand pretrial diversion options, and address racial disparities in pretrial outcomes.

- Indigent defense improvement. Grants to expand access to effective legal representation for indigent defendants. Funds may be used to hire and repay student loans, expand access to indigent defense counsel, institute policies to reduce caseloads, provide trainings for indigent defense counsel, and address racial disparities in defense outcomes.

- Prosecutorial reform. Grants to change prosecutor policies to improve accountability and transparency. Funds may be used to strengthen prosecutorial oversight, expand post-arrest diversion options, reform discovery processes, establish developmentally appropriate procedures for youth and young adults, and address racial disparities in prosecutorial outcomes.

- Sentencing reform. Grants to reduce mandatory minimum sentences and promote fairness in sentencing outcomes. Funds may be used to identify and address disparities in sentencing outcomes, reform sentencing practices, and reduce the number of individuals incarcerated under excessive sentences.

- Incarceration reform. Grants to transform correctional facilities and improve outcomes for incarcerated individuals. Funds may be used to strengthen correctional programming and supportive services including behavioral health, employment, and education; prevent sexual assault and violent victimization in correctional facilities; limit the use of restrictive housing; develop emergency preparedness plans for correctional systems; and address racial disparities in incarceration.

- Post-conviction reform. Grants to reduce barriers to successful reentry and completion of community supervision. Funds may be used to strengthen reentry and supervision services, reduce reincarceration for technical violations, limit collateral consequences of conviction, increase and streamline expungement and record-sealing processes, reform clemency and parole practices, and address racial disparities in post-conviction outcomes.

Formula

- Discretionary allocation. The U.S. attorney general may allocate up to 10 percent of the total amount appropriated to discretionary grants.

- Formula. 50 percent of funds shall be allocated to states, U.S. territories, and tribal governments based on their share of the total U.S. population. 50 percent of funds shall be allocated based on the locality’s share of the total nonfederal incarcerated population.

Requirements

- Data and policy requirements. States may not receive grants if they do not comply with the Death in Custody Reporting Act.

- Criminal justice reform council. In order to qualify for formula grants, each state must appoint a criminal justice reform council. No more than 45 percent of members may be drawn from government or criminal justice system agencies. Council membership must include representatives from organizations serving underrepresented communities, including criminal justice system-affected communities and formerly incarcerated persons.

- Annual plan. In order to qualify for an annual grant, each state’s criminal justice reform council must prepare an annual plan, or annual update of such plan, that addresses no fewer than two of the eight purpose areas. The contents must include the state’s plan for distributing grants required to units of local government. The plan is a requirement for states to remain eligible for grants.

- Transparency. States must make readily available on their website: (1) the annual plan developed by the criminal justice reform council; (2) data on actual usage of funds under this grant; and (3) transcripts and videos of meetings of the criminal justice reform council.

2. Community-based public safety formula grant

Grants to states, U.S. territories, and tribal governments to support community-based solutions to public safety issues and prevent crime and violence

Funding level: $750 million

Purpose areas

- Youth violence prevention. Grants to support violence prevention programming for at-risk young people. Funds may be used to provide mentoring and counseling services, youth employment programs, after-school youth development programs, and school-based violence prevention programming.

- Violence intervention. Grants to support nonpunitive interventions for individuals at highest risk of violence. Funds may be used to provide services such as violence interruption and incident response, intensive mentoring and case management, hospital-based violence interventions, and trainings or professional development for front-line violence intervention professionals.

- Civilian first responders. Grants to support civilian first responders. Funds may be used to establish and/or evaluate a branch of civilian first responders and provide trainings for civilians to respond to behavioral health crises, substance misuse, homelessness, and other social service needs.

- Community-driven initiatives. Grants to participatory budgeting initiatives that direct funding toward resident-identified priorities related to community health and safety. Funds may be used to support planning processes, capacity building, and implementation of resident-identified projects.

- Restorative justice. Grants to support restorative justice programs. Funds may be used to establish and/or expand programs that respond to harm caused by crimes without criminal justice sanctions.

- Offices of neighborhood safety. Grants to support civilian offices of neighborhood safety within local governments. Funds may be used to support the establishment of an office, program costs, and improvements to data infrastructure and capacity.

Formula

- Discretionary allocation. The U.S. attorney general may allocate up to 10 percent of the total amount appropriated to discretionary grants.

- Formula. Funds shall be allocated to states, U.S. territories, and tribal governments based on their share of the total U.S. population.

Requirements

- Data and policy requirements. No funds appropriated under this grant shall be allocated to state, local, or tribal criminal justice agencies, to include law enforcement, corrections, judicial systems, prosecutors, defenders, and any other division of the criminal justice system.

- Public safety council. In order to qualify for formula grants, each state must appoint a public safety council. No more than 45 percent of members may be drawn from government, law enforcement, and public safety agencies. Council membership must include representatives from organizations serving underrepresented communities, including criminal justice system-affected communities and formerly incarcerated persons. Membership of the public safety council shall prioritize individuals who represent jurisdictions with the highest annual number of Group A violent crimes of the National Incident Based Reporting System.

- Annual plan. In order to qualify for an annual grant, each state’s public safety council must prepare an annual plan or an annual update of its plan. The contents must include the state’s plan for distributing grants required to units of local government. The plan is a requirement for states to remain eligible for grants.

- Transparency. States must make readily available on their website: (1) an annual plan developed by the public safety council; (2) data on actual usage of funds under this grant; and (3) transcripts and videos of the meetings of the public safety council.

3. Community-oriented police reform and accountability formula grant

Grants to states, U.S. territories, and tribal governments to strengthen accountability for law enforcement, advance reforms in police practices, and enhance transparency in policing

Funding level: $500 million

Purpose areas

- Police accountability. Grants to strengthen police accountability and oversight. Funds may be used to support state-led pattern and practice investigations, independent investigation processes for officer misconduct, officer misconduct registries, Serious Incident Review Boards, and civilian oversight bodies.

- Fairness in policing. Grants to reduce disparities and promote fairness in policing. Funds may be used to identify and address drivers of racial and ethnic disparities, support positive police engagement with the community, and provide trainings on implicit and explicit bias, procedural justice, and discriminatory profiling.

- Police use of force. Grants to reduce incidences of use of force by law enforcement. Funds may be used to revise policies on when officers are permitted to use force, including deadly force; support trainings on de-escalation and the duty to intervene; and improve data collection on use-of-force incidents.

- Police crisis response. Grants to improve law enforcement responses to individuals in crisis. Funds may be used to support prearrest diversion options, crisis intervention and behavioral health trainings, overdose prevention and reversal resources, and partnerships with clinicians to provide appropriate responses to calls for service.

- Police transparency. Grants to promote transparency in policing. Funds may be used to support body-worn and dashboard cameras, improvements to data infrastructure, and compliance with federal data reporting requirements, including through the National Incident-Based Reporting System and the Death in Custody Reporting Act.*

- Police workforce and wellness.** Grants to support a diverse, well-qualified police workforce. Funds may be used to incentivize higher education among officers, promote diversity in recruitment and hiring, and support mental health and wellness services for officers.

**These funds may not be used to support law enforcement salaries. The DOJ may provide a waiver allowing funds to be used for salaries only once a law enforcement agency has demonstrated substantial progress toward the goals of this grant. Individuals hired through this grant should meet minimum age, education, and residency requirements.

Formula

- Discretionary allocation. The U.S. attorney general may allocate up to 10 percent of the total amount appropriated to discretionary grants.

- Formula. Funds shall be allocated to states, U.S. territories, and tribal governments based on their share of the total U.S. population.

Requirements

- Data and policy requirements. States may not receive grants if they do not comply with George Floyd Justice in Policing Act certifications and requirements, including reporting on officer certification and de-certification, reporting on police use of force and misconduct, supporting pattern-or-practice investigations, and enacting a ban on chokeholds. States also must enact a ban on ticket and arrest quotas and ban direct funding of law enforcement agencies through civil asset forfeiture.

- Policing reform council. In order to qualify for formula grants, each state must appoint a policing reform council. No more than 45 percent of members may be drawn from government, law enforcement, and public safety agencies. Council membership must include representatives from organizations serving underrepresented communities, including criminal justice system-affected communities and formerly incarcerated persons.

- Annual plan. In order to qualify for an annual grant, each state criminal justice reform council must prepare an annual plan or an annual update of its plan. The contents must include the state’s plan for distributing grants required to units of local government. The plan is a requirement for states to remain eligible for grants.

- Transparency. States must make readily available on their website: (1) an annual plan developed by the policing reform council; (2) data on actual usage of funds under this grant; and (3) transcripts and videos of the meetings of the policing reform council.