Author’s note: CAP uses “Black” and “African American” interchangeably throughout many of our products. We chose to capitalize “Black” in order to reflect that we are discussing a group of people and to be consistent with the capitalization of “African American.”

The “tough on crime” policy agenda that rose to popularity in the 1980s and 1990s left a damaging and enduring legacy across the country, especially in communities of color. Researchers have largely discredited the tough-on-crime theory—which espouses punitive enforcement and lengthy sentences for all crimes—finding that increased reliance on incarceration had little impact on crime rates.1 An increasing number of policymakers are now working to address the harms caused by decades of overpolicing and overcriminalization by amending sentencing laws, advancing pretrial and bail reforms, and providing opportunities for those returning from incarceration.2

But the tough-on-crime era caused lasting harms that cannot be fixed merely through a change in laws or policies. Relationships between residents and law enforcement, who are the front-line representatives of the criminal justice system, remain strained—and in many cases, nonexistent. Distrust in law enforcement often goes hand in hand with distrust in local government as a whole, likely because police are one of the most visible representatives of government within the community.3 This may be particularly true in low-income neighborhoods, where the rise of overpolicing coincided with a lack of government investment in job opportunities, high-quality schools, and essential health and social services.4

These same communities continue to feel the impact of city public safety practices, often without having a place at the decision-making table where these policies are developed. While community engagement efforts such as town halls are commonplace among city agencies, residents who are wary of local officials are unlikely to participate in public forums or other traditional methods for soliciting feedback on city practices or proposed reforms.5 As a result, typical efforts to engage the community may fail to capture the perspectives and priorities of diverse communities, reinforcing patterns of disadvantage and distrust in local government and law enforcement.6

Breaking this cycle requires cities to adopt inclusive strategies for engaging communities historically targeted by overpolicing and government disinvestment. One such approach is NeighborhoodStat, a joint problem-solving process developed by the New York City Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice.7 NeighborhoodStat empowers residents of high-crime public housing developments to work directly with city leaders to strengthen public safety by addressing the social, economic, and environmental conditions that are linked to crime. Research shows that communities are safer when residents have access to stable jobs, high-quality schools and social services, and clean and vibrant public spaces. Importantly, NeighborhoodStat relies on active participation and buy-in from members of the community, establishing the legitimacy of the city’s efforts to strengthen public safety.

This issue brief explores the need for inclusive community engagement strategies, discusses the benefits that NeighborhoodStat has had for New York City communities, and identifies lessons learned to inform how other cities can strengthen safety through community empowerment.*

Breaking the cycle of disinvestment and distrust

Even as some politicians work to roll back tough-on-crime laws, relationships between law enforcement and residents remain fraught in many communities of color. A recent survey of low-income, predominantly Black neighborhoods across the country showed that fewer than one-third of residents trust the police.8 The same survey, conducted by the Urban Institute, found that roughly half of residents feared that their words or actions “might be misinterpreted as criminal by the police due to [their] race/ethnicity.”9

To understand the significance of these findings, it is important to consider that the police are one of the most visible representatives of the government within the community.10 Perceptions of the police are often linked to trust of government as a whole, which can affect participation in civic life.11 Data from a survey of 15,000 young people conducted by researchers Amy Lerman and Vesla Weaver show that young adults who have been incarcerated or who the police have stopped and questioned are less likely to trust the government and more likely to avoid contact with public officials.12 One respondent explained that he does not contact his elected representatives for fear that they will try to “put me in jail and leave me as a troublemaker.”13 This sentiment was echoed by a community leader in Detroit, who explained that many young African American men in her area feel uncomfortable participating in public meetings out of concern that they would be “perceived as criminals” by city officials or that their contributions would not be taken seriously “because of their unfamiliarity with policy language.”14

In neighborhoods where trust in government has been broken, residents may also be less likely to seek out city services. Hundreds of jurisdictions across America operate a 311 telephone line that residents can call to request nonemergency assistance from city agencies, which use the call system to prioritize resource allocation.15 But not all residents are equally likely to request city support through mechanisms such as 311. A study of 311 call data in New York City found that higher-income areas and neighborhoods with a greater percentage of white residents were more likely to submit requests for government services.16 Research has also demonstrated that living in a neighborhood with higher levels of aggressive policing—measured by the percentage of all police stops that involve use of force—reduces the likelihood that residents will call 311.17 The net effect is that residents’ needs may go unmet.

In the absence of inclusive strategies for engaging diverse communities, local policy agendas may not always reflect the perspectives and priorities of residents most affected by overcriminalization and disinvestment. The mismatch is apparent when it comes to approaches to strengthening public safety. Government officials often create policies that favor criminal justice system responses, without considering residents’ diverse perspectives on public safety.18 In Atlanta, for example, low-income residents identified access to housing, transportation, and affordable energy as key public safety priorities.19 But for every $1 spent on policing in the city, only 11 cents go to the Atlanta Department of Planning and Community Development, which funds both transportation and affordable housing.20 The mismatch between official policies and communities’ values can reinforce a pattern of distrust in government among residents, who may feel that public officials are not serving the needs of their community.

New York City’s NeighborhoodStat initiative

To break the cycle of disinvestment and distrust, city officials must adopt engagement strategies that are inclusive of communities that have historically been left out of government decision-making processes. One such effort is NeighborhoodStat, an initiative launched by the city of New York to empower residents of high-crime communities to help shape the city’s public safety agenda within their neighborhoods and build partnerships with city agencies and community organizations.

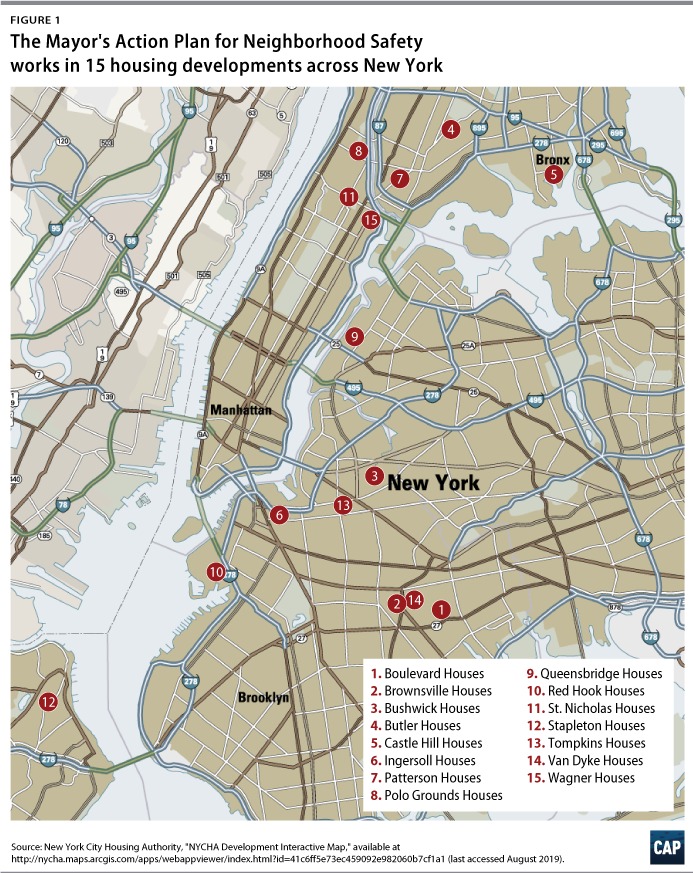

NeighborhoodStat was envisioned by the New York City Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice (MOCJ) as a strategy for bringing residents together with city leadership to jointly address persistent challenges within the city’s public housing developments.21 NeighborhoodStat was launched in 2016 by Mayor Bill de Blasio (D) as part of the Mayor’s Action Plan for Neighborhood Safety (MAP), a public safety initiative established to address the root causes of violence in 15 public housing developments across the city.22 (see map below) NeighborhoodStat empowers residents to set their own agenda for addressing the issues affecting the safety of their neighborhoods and puts in place a structure allowing them to partner with city leaders to bring their vision into reality.

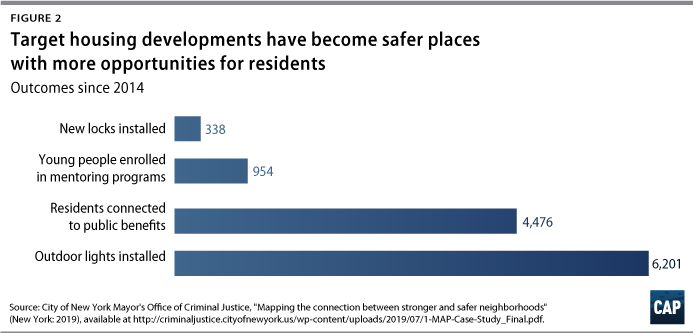

NeighborhoodStat begins with a community-led strategic planning process to identify key priorities for strengthening the quality of life within the housing developments. Priorities include everything from improving the physical environment through vibrant communal spaces and security features such as exterior lighting and secure locks, to improving the opportunities available within the community through youth development programs and connections to neighborhood-based public benefits and supportive services. Residents then meet directly with city agencies and stakeholder groups to discuss analyses of neighborhood-level data, pinpoint solutions, and realign city resources to better meet community needs.23

Driving change with a new approach to public safety

NeighborhoodStat was originally inspired by CompStat, a management tool developed by the New York City Police Department (NYPD) that uses timely data analysis to hold officers accountable for crime and enforcement outcomes.24 The models share some similarities—both rely on regular in-person stakeholder meetings to track progress and set priorities—but NeighborhoodStat and CompStat represent different approaches to public safety. When the NYPD first introduced CompStat in 1994, officers were rewarded for boosting arrest rates, particularly for low-level infractions, and for increasing the use of stop and frisk.25 These practices resulted in the overcriminalization of countless New Yorkers, predominantly from Black and Latinx communities, and further eroded relationships between members of law enforcement and the residents they serve.26

In contrast, NeighborhoodStat offers an avenue for cities to strengthen public safety while rebuilding trust in government. NeighborhoodStat partners city leaders and residents to address public safety concerns in a way that responds directly to the needs of the community. Importantly, NeighborhoodStat fosters meaningful partnerships between residents, community groups, and the many city agencies with a stake in public safety—not just police. The NYPD is a valued partner in the initiative, but the police alone cannot address the social, economic, and environmental conditions that affect public safety. Agencies across City Hall have a role to play in strengthening safety, since crime is more likely to occur when people are unable to meet their most basic needs: an education,27 a stable income,28 and access to the food29 and health care30 they need to survive. Government investments that focus on addressing these underlying social needs can help strengthen public safety, as can investments that improve the physical environment in the community. When public places such as parks, sidewalks, or community centers are well-lit and well-maintained, they offer fewer opportunities for crime to occur.31 Residents are more likely to congregate and connect with one another in vibrant community spaces, and their presence can help deter crime in these locations.

Renita Francois, executive director of the Mayor’s Action Plan for Neighborhood Safety, explains that the initiative’s overarching goal is to “lend resident voice to understanding the way that the city should be organizing its resources.”32 To do so, the city gives residents space to get creative with their responses to violence. For example, crime was trending upward in the Van Dyke housing development, located in the Brownsville neighborhood of eastern Brooklyn.33 Access to food is also a major concern for residents of this neighborhood, who have to travel long distances to shop at high-quality grocery stores.34 In response to upticks in violence, residents have launched pop-up food markets and cooking demonstrations in the areas that have experienced concentrated public safety issues.35 These locations are now populated with positive activity that serves as a crime deterrent, while at the same time addressing food inequity in the community.

While this approach may seem like a radical departure from traditional policing-focused methods of crime reduction, the model is firmly grounded in evidence on the factors that influence neighborhood safety. Research consistently shows that communities with high concentrations of poverty and income inequality are also more likely to experience crime and violence.36 Higher crime rates have also been linked to inadequate access to vital community resources such as social services, health care, education, and infrastructure.37 Rather than trying to out-police crime—a strategy that can create more harm than good—the city of New York is improving public safety by channeling resources toward meeting specific community needs. The city has made significant investments in crime prevention strategies backed by research, including youth mentoring, summer jobs programs, and violence interruption services. (see text box)

“When we think about deterring crime, we need to pursue a broad range of strategies beyond traditional law enforcement. A well-lit street deters crime better than a dark alley, just as opportunities for work and play promote safety better than disadvantage and disconnection.”[38. New York City Office of the Mayor, “Mayor de Blasio Announces Pioneering Study on How Outdoor Lighting Reduces Crime,” Press release, March 11, 2016, available at https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/242-16/mayor-de-blasio-pioneering-study-how-outdoor-lighting-reduces-crime.]

Elizabeth Glazer, director of the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice

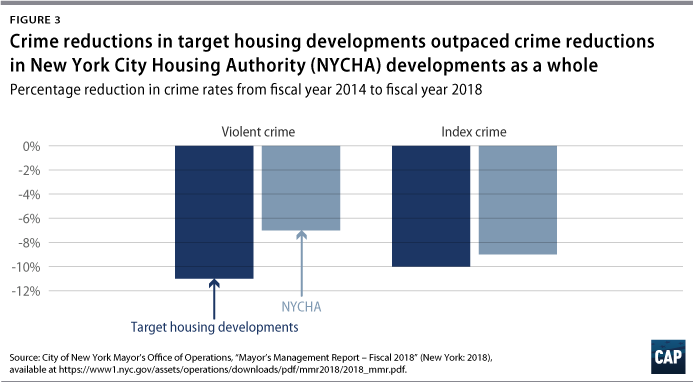

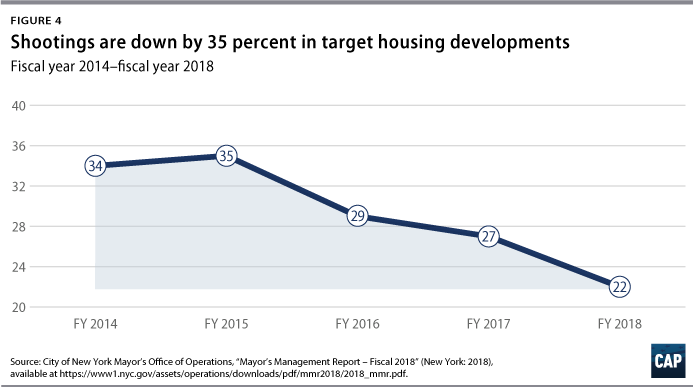

New York’s approach has proved effective. When MAP was founded in 2014, the target communities accounted for nearly 20 percent of violent crime across the city’s 328 public housing developments.38 Since then, crime and violence have fallen significantly. Target communities have experienced an 11 percent reduction in violent crime and a 10 percent reduction in the major crime categories known as index crimes.39 And while crime rates have been trending downward across the city of New York, target developments have outpaced other New York City Housing Authority developments in crime reduction.40 Participating public housing developments have actually seen a steeper decline in shootings than in the city as a whole, with shootings falling by 35 percent from fiscal year 2014 to fiscal year 2018.41

Crisis Management System

NeighborhoodStat works closely with agencies across City Hall, including the Mayor’s Office to Prevent Gun Violence. The Office to Prevent Gun Violence oversees the city’s Crisis Management System, a network of violence interruption programs operated by nonprofit providers in 17 police precincts across the city.42 These programs are based on Cure Violence, a model that relies on credible messengers—people with established ties to the community, many of whom were previously involved in violence—to reach individuals at highest risk of being affected by gun violence and mediate disputes before they turn violent.43

The Crisis Management System operates in several MAP developments, including Boulevard Houses, located in Brooklyn’s East New York neighborhood.44 At Boulevard Houses, the city works with Man Up! Inc.,45 a nonprofit service provider founded by grassroots community activist Andre T. Mitchell.46 Mitchell, who now serves as the organization’s executive director, says that Cure Violence resonated with the community, in part because it mirrored the work that they were already doing in East New York.47 As an established program, Cure Violence had rigorous evaluation data that “spoke value to the work that we were doing out here,” Mitchell explained in an interview with the author. “It was helpful because it gave us definition.”48 As Mitchell explained it, violence is not usually caused by drugs or gangs or territory disputes but instead by minor interpersonal disagreements that eventually turn violent.49 It’s the role of Man Up! Inc.’s teams of trained credible messengers to help iron out these interpersonal issues before they escalate. Credible messengers also serve as mentors for young people in the community, providing them with targeted connections to resources and supportive services.50 This is an integral part of the program’s success, according to Mitchell. “You can’t just ask them to take a gun out of their hand and not use it if you don’t have anything to replace it with,” he said.

The movement to engage credible messengers represents a profound shift toward valuing the experiences and expertise of people with lived experiences in the community, including those previously involved in violence. “We have members of the community that are now looked upon in a whole different light,” Mitchell said. “These guys are mentors, they’re role models, they’re fathers and mothers, they’re taxpayers, they’re really civically involved, they’re really doing their part.” So far, their efforts have been working. Man Up! Inc. has been associated with a 50 percent reduction in gun injuries in the neighborhood, whereas similar communities experienced only a 5 percent drop during the same time period.51

How NeighborhoodStat works on the ground

NeighborhoodStat empowers residents to help shape the city’s response to public safety concerns in their community. The NeighborhoodStat process is guided by a resident leadership team, composed of roughly 15 community members across age groups who participate in trainings to build capacity and understand principles of crime prevention.52 Each team receives support from a dedicated engagement coordinator—hired and trained by the city’s partners at the Center for Court Innovation, a local nonprofit organization—who facilitates ongoing dialogue among neighbors, city agencies, and community organizations. NeighborhoodStat teams conduct interviews and surveys to identify their fellow residents’ biggest concerns and understand what they would most like to see change in their housing development. Leadership teams host local NeighborhoodStat meetings in the development, where residents are invited to give feedback on the plan and discuss their priorities directly with city agency staff, often over a shared meal.53 The strategic planning process is also informed by analysis of data on employment, health, infrastructure, youth engagement, and crime, which helps NeighborhoodStat teams further understand patterns of need and opportunity within the development.

The strategic planning process culminates in a central NeighborhoodStat meeting, which convenes resident teams and leadership from the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, the NYPD, NYCHA, and dozens of other city agencies and community-based service providers.54 Each housing development participates in two NeighborhoodStat meetings per year, with each meeting involving three or four developments over the course of several hours.55 Through a discussion facilitated by MOCJ, the group unpacks the issues identified by resident leaders and makes commitments to support solutions.

The meetings cover a diverse set of issues that influence the quality of life within the development. During a March 2019 NeighborhoodStat meeting that the author attended, residents from St. Nicholas Houses discussed the findings of a site audit, pinpointing a handful of locations where crime is most common, including a poorly maintained playground and several apartment buildings where young people congregate to engage in illegal activity.56 The team also cited statistics showing that a disproportionately high percentage of young residents of the St. Nicholas development are neither in school nor employed. Based on these findings, the NeighborhoodStat team requested support from city partners in expanding development opportunities for young people and cleaning up neglected public spaces, such as the playground, that attract illegal behavior. Residents also requested better signage outlining proper garbage disposal procedures to prevent garbage from piling up. Although NYCHA had placed signs and stickers on the walls previously, the instructions were only in English and the signage and stickers were often torn down. In response, NYCHA committed to translating signs and stickers into multiple languages and educating its staff to replace signage that had been removed to ensure that there was always adequate messaging.

Importantly, city agencies are held accountable for the promises made during NeighborhoodStat meetings. At the conclusion of each NeighborhoodStat meeting, agencies walk away with a to-do list that includes the tasks identified during the discussion. The set of NeighborhoodStat meetings conducted during spring 2017 yielded 175 tasks for partners, 81 percent of which were completed by that fall.57

Lessons learned

Since its launch in 2016, NeighborhoodStat has yielded a number of lessons for promoting successful problem-solving processes. Although it was developed in the nation’s largest city, NeighborhoodStat is focused on micro-level communities; thus, it offers lessons for jurisdictions of all sizes seeking to strengthen public safety through community empowerment.

Value the voices of the community

NeighborhoodStat meetings create a space where power is shared among all participants, from residents to city agency leadership. City leaders have taken concerted action to disrupt the traditional power dynamic, where government agencies hold all the cards, to ensure that community voices are not only encouraged but valued during the NeighborhoodStat process.

These collaborative efforts begin with the choice of meeting venue. Early iterations of NeighborhoodStat were hosted at New York City Police Department headquarters, which may have unintentionally reinforced “police-centric” power dynamics.58 Today, however, meetings are held at local educational institutions or City Hall. During meetings, participants pass microphones around a large table rather than speaking at an elevated dais. Even the seating arrangements are intentional: City leadership and NYPD officers sit scattered among the resident teams rather than on opposing sides of the table.59

MAP Executive Director Renita Francois says that these efforts to create a level playing field have “definitely changed the dynamic of the conversation.”60 The result is a collaborative discussion that places significant value on the expertise of residents, with the understanding that they know their communities better than anyone else and thus are best situated to identify challenges and potential solutions. In addition, with their experience navigating city services, residents are uniquely qualified to help city agencies rethink the way that they deliver resources. “They can tell you everything wrong with [an agency’s] service delivery and how people access the service—and provide you with a solution,” Francois explains.61 She’s also found that city agency leadership is often more receptive to feedback when it comes directly from residents, rather than a top-down mandate from the mayor’s office.

Share information widely and early

NeighborhoodStat meetings are most productive when all participants come ready to contribute to the conversation and make concrete commitments to support the needs of target housing developments. To maximize the effectiveness of NeighborhoodStat, the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice developed procedures to lay the groundwork for meetings and create a shared sense of purpose among all partners.

Early in the evolution of NeighborhoodStat, information was concentrated in the hands of lead city agencies. MOCJ hosted preparation calls with the New York City Housing Authority and the NYPD in advance of NeighborhoodStat meetings, sharing information on the concerns and requests that they thought residents would raise. Meanwhile, other partners entered NeighborhoodStat with little foresight into what the meeting would entail and nervous about how events would play out.62

MOCJ has since refined the NeighborhoodStat process to ensure that everyone has access to the same information in advance of a meeting. Now, preparation phone calls include all NeighborhoodStat partners.63 Additionally, policy briefs that summarize the findings of each development’s strategic planning process are distributed to city agency partners in advance of each meeting.64 These documents detail the key issues in the housing development, citing both residents’ experiences and data analyses, and discuss suggested next steps for addressing these challenges. This advance notice allows partners to proactively identify resources available within their agencies to support the development and arrive at the meeting ready to make firm commitments to meet residents’ needs.65

Bring partners to the table

To implement a holistic response to public safety issues, NeighborhoodStat must be inclusive of all agencies with jurisdiction over issues related to community well-being. Since launching NeighborhoodStat, MOCJ has worked to expand the scope of engagement to include nearly 50 partner organizations, each of which brings different assets and resources to the table. The list of partners is wide-ranging and includes representatives from city agencies, educational institutions, social service providers, workforce development programs, community centers, violence interruption initiatives, youth engagement programs, conflict mediation services, economic development partnerships, affordable housing developers, alternatives to incarceration and reentry programs, community arts initiatives, nutritional education and food access programs, and more.66

It was not always easy, however, to bring potential partners onboard. Some partners initially expressed skepticism at the idea that their agency’s work was related to issues of public safety. MOCJ found that successful engagement hinged on overcoming that skepticism by drawing clear connections between a potential partner’s mission and broader goals of NeighborhoodStat. As Francois explained, it was a question of “helping people transition their mindset from ‘This doesn’t apply to me’ to ‘How does my issue interact with this?’”67

Conclusion

For too long, the communities most affected by crime have been left out of conversations about strengthening public safety. NeighborhoodStat offers a concrete strategy for city leaders to shift away from the status quo. Developed as part of New York City’s Mayor’s Action Plan for Neighborhood Safety, NeighborhoodStat is a tool for empowering community members to help shape their responses to public safety concerns by addressing the environmental and social issues that affect community stability and well-being. Importantly, NeighborhoodStat is an inclusive process that intentionally creates space for residents to engage directly with city leadership to identify and implement solutions that are responsive to community needs.

The program’s successes illustrate the value of creative, community-driven interventions and stand as a reminder of the need to broaden the understanding of community engagement and public safety. Not only have crime rates dropped in the participating housing developments, but NeighborhoodStat has also helped boost youth civic engagement, build safer and more vibrant physical spaces for residents, create new opportunities for economic and educational growth, and forge stronger partnerships between government and the residents it serves. With its neighborhood-level focus, NeighborhoodStat offers lessons for cities of all sizes to strengthen public safety by empowering communities to shape their own responses to violence.

* To inform this brief, the author conducted interviews with NeighborhoodStat partners and stakeholders and attended a NeighborhoodStat meeting on March 25, 2019, focused on three housing developments—Queensbridge Houses, St. Nicholas Houses, and Polo Grounds Towers.

Betsy Pearl is a senior policy analyst for Criminal Justice Reform at the Center for American Progress.

This issue brief was created with support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation as part of the Safety and Justice Challenge, which seeks to reduce overincarceration by changing the way America thinks about and uses jails.