See Also

This issue brief contains a correction.

The legacy of the Violent Crime Control Act and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, better known as the crime bill, has re-emerged in the national debate around criminal justice reform and public safety.1 Many consider the crime bill to be one of the cornerstone statutes that accelerated mass incarceration.*2 But the law’s negative effects did not end there. States and localities were incentivized through a massive infusion of federal funding to build more jails and prisons and to pass so-called truth-in-sentencing laws and other punitive measures that simultaneously increased the number and length of prison sentences while reducing the possibility of early release for those incarcerated.3

It has been well-documented that these policies were failures.4 Their cost to society came not only from the staggering amount of taxpayer dollars that were invested in enforcement, but also from the disproportionate incarceration of a generation of African American men in the name of public safety. Moreover, tough-on-crime measures—specifically longer incarceration sentences—have had at best a marginal effect on improving public safety.5

Elected leaders today are attempting to unwind some of the most harmful effects of the crime bill through criminal justice reform measures. As part of that reform effort, a number of cities have pursued public health models and community-based strategies alongside innovative policing approaches. However, the effectiveness of those efforts has been and will continue to be muted because the machinery that the crime bill created and preserved has never stopped churning. The same funding streams that overwhelmingly support enforcement activities over proven preventative and restorative solutions continue to this day—albeit with tweaks around the edges. States still look to build new jails and prison facilities,6 even as crime rates remain near historic lows.7 At the same time, Congress continues to advocate for new criminal statutes and higher criminal penalties, even as it proposes to lower some mandatory minimum sentences.8

Before considering what additional reforms are needed to fix a severely broken criminal justice system, U.S. elected leaders must first stop supporting the very mechanisms that caused the failure in the first place. Borrowing from the field of medicine, lawmakers must embrace the notion of “first, do no harm”—or more accurately, “do no more harm.”9 This issue brief spotlights four problematic tough-on-crime policies exacerbated by the crime bill that remain in place and continue to undermine reform efforts. Only when these destructive policies are reversed can the rebuilding of the criminal justice system truly take root to prevent harm in the future.

Moving from punishment to preventive care

Shifting away from the infrastructure created by the crime bill is not easy, especially because much of the American public equates public safety with policing, prosecutors, and prisons and jails. Polling shows that despite significant drops in the crime rate, the majority of the general public believes that crime has gotten worse.10 When the public feels tense about their safety, the solution they seek is often more police officers, more convictions, and longer sentences. When tensions diminish or crime rates decrease, mayors or governors proudly stand at a podium with law enforcement to boast of the achievement.

Not surprisingly, the footprint of policing has expanded dramatically in recent years. The default solution is to call on law enforcement to respond to any issue that has the potential to affect a community’s safety—whether it is substance misuse and addiction, mental health issues, truancy, or homelessness. In almost every situation, law enforcement’s main tool is the power to arrest and incarcerate, thereby unnecessarily enlarging the criminal justice system simply because other solutions or responses are unavailable. Requiring the law enforcement apparatus to solve societal issues that it is neither trained nor equipped to handle overburdens the justice system and prevents it from properly executing its limited core responsibilities.

We’re asking cops to do too much in this country ... Every societal failure, we put it off on the cops to solve. Not enough mental health funding, let the cops handle it … Schools fail, let’s give it to the cops … That's too much to ask. Policing was never meant to solve all those problems.” – Former Police Chief David Brown, Dallas Police Department

Brady Dennis, Mark Berman, and Elahe Izadi, “Dallas police chief says ‘we’re asking cops to do too much in this country,’" The Washington Post, July 11, 2016, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2016/07/11/grief-and-anger-continue-after-dallas-attacks-and-police-shootings-as-debate-rages-over-policing/?utm_term=.2357e1c9da1e.

The transition to a paradigm where public safety does not depend exclusively or primarily on the police and the criminal justice system may be difficult. But a lesson can be taken from the transformation of the practice of medicine, which in recent years has come to emphasize holistic and preventive care. Instead of relying on surgical or other invasive interventions to treat illnesses and diseases, medicine now invests heavily in preventing illnesses by encouraging healthy lifestyles and addressing health issues early with noninvasive treatments.11 As former Sen. Tom Harkin (D-IA) noted when Congress was considering the Affordable Care Act, a “truly transformational element” of the health care law was to “jump-start America’s transition from our current sick care system into a genuine health care system, one that is focused on keeping us healthy and out of the hospital in the first place.”12

That same type of transformation must happen with America’s approach to public safety. The criminal justice system can be likened to hospitalization or a surgical intervention, which is never removed as an option but is reserved for the most serious situations. Unnecessary arrests and incarcerations, like surgeries, run the risk of serious complications.13 Even when invasive interventions are necessary, care must always be taken during the procedure to minimize trauma and promote a quick recovery. But the overall goal and the bulk of resources should be devoted to keeping people out of the operating room or, in this case, out of the criminal justice system in the first place.

First, do no more harm

Unfortunately, the United States’ investments in public safety continue to overwhelmingly prioritize arrests and incarceration over measures that prevent crime from occurring. As elected leaders reflect on the 1994 crime bill, it is not enough to state that the country is learning lessons from the bill’s failings. Instead, elected leaders must take concrete action to halt the very mechanisms that the legislation created—and that continue to undercut meaningful criminal justice reform. Even the 1994 crime bill included a section devoted to crime prevention activities.14 But in the end, many of these programs were either repealed or never received any funding in the first place.15 Going forward, leaders must make the following commitments to stopping the ongoing harm inflicted by the 1994 crime bill.

No blank checks

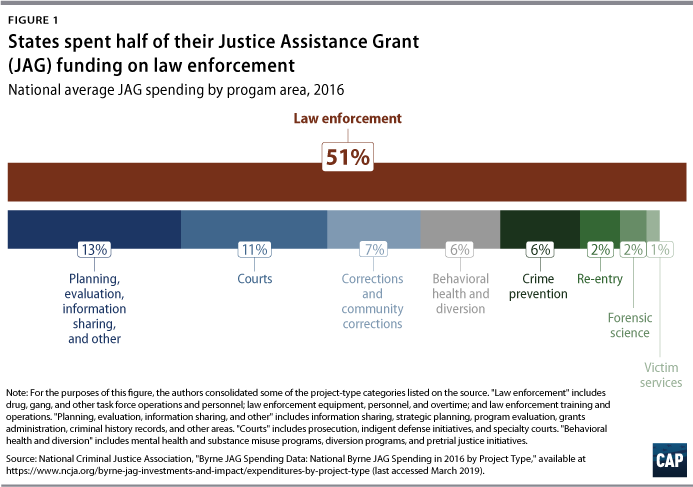

Any serious effort to halt the ongoing damage wrought by the crime bill must target the money—the law’s primary vehicle for influencing state and local policy. Every year, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) distributes millions of dollars to states and localities through funding grants started under the crime bill—the vast majority of which is funneled directly to law enforcement agencies with few strings attached.16 The single largest source of federal public safety funding today is the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) Program, which has its roots in a massive mid-1990s block grant for local law enforcement agencies.17 Cities and states can use JAG to support a wide array of public safety functions—from violence prevention to indigent defense to mental health treatment.18 The reality, however, is that most JAG funds go directly to law enforcement.

Nationally, according to the latest detailed data from 2016, 58 percent of JAG funds were used to support law enforcement and corrections functions, while only 6 percent went to crime prevention.19 And more than one-quarter of all JAG funds were used to operate drug taskforces,20 which have multiplied exponentially nationwide since the infusion of federal funds.21 These national averages hide an even starker contrast at the state level. A Center for American Progress analysis shows that in 14 states, more than $9 out of every $10 in JAG funds went to police departments and prosecutors’ offices.22 Four states—Maine, Montana, West Virginia, and Wyoming—devoted a full 100 percent of JAG funds to law enforcement.23 In 22 states, crime prevention efforts went completely unfunded.24

JAG and other public safety dollars from the federal government cannot continue to be structured in a way that results in the vast majority of the funds going to support law enforcement. The federal government must intentionally invest in a new vision for stronger, healthier communities and no longer simply distribute money to states with the hope that they spend it appropriately. This can be accomplished in part by requiring states to devote substantial percentages of JAG funds to areas besides law enforcement in order to ensure a comprehensive approach to public safety. Additionally, Congress could change the eligibility formula for receiving JAG funds so that it is based not only on population and annual crime rate data, but also on other indicators of community well-being such as measures of poverty, unemployment, and educational attainment rates. Congress could also substantially increase the amounts that it appropriates to JAG—but only if that escalation is set aside for purpose areas that are perpetually underfunded by public safety dollars such as crime prevention and mental health and substance abuse treatment. Through a radical realignment of DOJ’s investments, lawmakers can reinvest billions of dollars into communities and effectively reshape the way that jurisdictions think about and carry out public safety efforts.

No easy path to new penalties

Enacting laws that authorize the incarceration of individuals is one of the most powerful and impactful responsibilities of legislators and elected leaders. Yet, Congress has not been shy—or particularly deliberative—about wielding this authority. The federal criminal code contains offenses and criminal penalties that are too numerous for experts to count. Recent estimates combining research from several sources show that approximately 5,000 federal statutes carry a criminal penalty—a 50 percent increase in the number of federal crimes since the 1980s.25 Already in the 116th Congress, which is less than three months old, lawmakers have introduced nearly 200 pieces of legislation that add or amend federal criminal statutes, and only a handful of them—for example, the Justice Safety Valve Act—are intended to reduce criminal penalties.26

For federal lawmakers, there are virtually no barriers to passing a new criminal statute or increasing a criminal penalty. Congress is under no requirement to know whether a new statute is necessary; if the increased penalties would deter or prevent future crimes; or what population would be affected most by the new statute. Even traditional procedures for any legislation such as conducting hearings and voting a bill out of a committee have been bypassed when deemed necessary. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, for instance, was another landmark tough-on-crime statute that infamously established the 100-to-1 powder versus crack cocaine sentencing disparity.27 That bill was introduced and signed into law within a span of just two months. According to the U.S. Sentencing Commission:

The sentencing provisions of the Act were initiated in August 1986, following the July 4th congressional recess during which public concern and media coverage of cocaine peaked as a result of the June 1986 death of NCAA basketball star Len Bias. Apparently because of the heightened concern, Congress dispensed with much of the deliberative legislative process, including committee hearings.28

Elected leaders should not add to the already cluttered criminal code. At the very least, they must substantially raise the bar that must be met to consider new crimes and criminal penalties. Current and future presidents should issue veto threats, making it clear that they will not sign any bill that increases criminal penalties or creates a new crime unless there is clear evidence that such a measure is not only necessary, but also that no other noncriminal justice solution could achieve the same result. Congress can pass a rule that requires a supermajority to pass any legislation that increases a criminal penalty or adds a new offense to the federal criminal code. Additionally, Congress should be required to produce data on who a new criminal statute or penalty would affect to ensure that it does not disproportionately criminalize people of color or other vulnerable communities. The lifelong consequences of incarceration and criminal records on people and their families are too harmful for lawmakers not to carefully consider whether a criminal statute is necessary.

No new jails and prisons

The 1994 crime bill accelerated the U.S. prison boom by authorizing more than $12 billion to subsidize the construction of state correctional facilities, giving priority to states that enacted so-called truth-in-sentencing laws.29 These laws, which require individuals to serve at least 85 percent of their sentence behind bars, have been shown to expand prison populations by increasing individuals’ length of stay.30 By 1998, truth-in-sentencing laws were in effect in 27 states, up from eight states before the crime bill’s passage. A majority of state officials cited the federal incentives as a driving force for adopting the truth-in-sentencing policy change.31 In the decade following the crime bill’s enactment, the number of correctional facilities nationwide jumped by 20 percent.32 The incarcerated population grew by 40 percent during the same period.33

The construction of new prisons and jails dangerously compels governments to make use of them.

While DOJ’s original truth-in-sentencing incentive program has lapsed, the federal government continues to subsidize the growth of correctional facilities. Most notably, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has spent $360 million to build jails in rural communities, using funds from a grant and loan program that was originally intended for rural economic development and infrastructure improvements.34 The Trump administration has approved approximately $106 million of this amount.35 These facilities are especially unnecessary today, considering the United States’ current low crime rates, yet jurisdictions see an opportunity to create jobs through the criminal justice system. More insidious, the construction of new prisons and jails dangerously compels governments to make use of them, thereby creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of criminalization. This vicious cycle must stop—starting with policymakers ending funding, resources, and incentives to build new jails and prisons.

No privatization

Elected officials have increasingly allowed private corporations to dictate the criminal justice system, undermining attempts at reform. Privatization is most visible in the corrections industry, where private prisons have expanded at an alarming rate. From 2000 to 2016, the number of people held in private prisons jumped by 47 percent—five times faster than the overall growth in incarceration.36 America’s two largest private prison companies—GEO Group Inc. and CoreCivic, formerly Corrections Corporation of America—amass more than $3 billion in revenue per year, roughly half of which comes from the federal government.37 The vast majority of the remaining revenue comes from lucrative contracts with state governments,38 which often include a guarantee that states will incarcerate enough people to fill the prison.39 Under a number of these agreements, states must pay a fee if the prison population dips below the quota, which is usually set at 90 percent of the prison’s total capacity, creating clear incentives for states to lock more people up for longer periods of time.40

As long as the criminal justice system is motivated by profit, it will continue to expand its reach and inflict undue harm on individuals and communities.

Private prisons, however, are just a sliver of the for-profit criminal justice industry. Private industry has permeated virtually every sector of criminal justice operations. Every year, bail bondsmen collect $1.4 billion in nonrefundable fees from defendants and their families; private vendors earn $1.6 billion selling goods in prison commissaries; and telephone companies collect $1.3 billion in exorbitant fees for calls from prisoners to loved ones and lawyers.41 Furthermore, private industry is undermining efforts to reduce reliance on incarceration by monetizing the use of community supervision. A private electronic monitoring company in California, for example, collects more than $750 in monthly fees from every individual on supervision who wears a monitoring device.42 This model not only expands the scope of mass supervision, but it is also designed to keep people trapped in a cycle of justice involvement. Anyone who is unable to afford the steep costs of electronic monitoring can expect to end up in jail, regardless of the nature of their alleged offense.

As long as the criminal justice system is motivated by profit, it will continue to expand its reach and inflict undue harm on individuals and communities. Elected officials must immediately end the use of profit-motivated vendors that have been allowed to dictate justice policy for too long. By severing the link between criminalization and profit, lawmakers can accelerate efforts to drastically reduce overall incarceration and supervision rates.

Conclusion

The 1994 crime bill systematized so-called tough-on-crime policies in the United States. Efforts to reform the criminal justice system, therefore, will always be labeled a first step until lawmakers embrace the concept of “first, do no more harm” and dismantle the instruments that actualize these policies. They must commit to investing in comprehensive public safety solutions; dramatically reducing reliance on incarceration; preventing unnecessary criminalization; and breaking the link between profit and the criminal justice system.

Ed Chung is the vice president for Criminal Justice Reform at the Center for American Progress. Betsy Pearl is a senior policy analyst for Criminal Justice Reform at the Center. Lea Hunter is a research assistant for Criminal Justice Reform at the Center.

*Correction: May 29, 2019: This issue brief has been updated to reflect that the crime bill is best known for a variety of reasons—not solely for how it addressed drug crimes.