As Congress returns from the August recess, one of its most pressing goals will be to pass a series of appropriations bills to fund the federal government for fiscal year 2018, which begins October 1, 2017. Criminal justice stakeholders across the country are paying particularly close attention to the FY 2018 Commerce, Justice and Science (CJS) appropriations bill. This bill not only controls the funding levels for federal criminal justice entities but also sets the amounts available to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) for grants to state and local government counterparts as well as researchers and service providers.

The importance of federal criminal justice resources has become even more pronounced in recent years as the movement to reform criminal justice systems and practices has gained steam. While comprehensive efforts to reduce the size of the federal criminal justice system face headwinds from the Trump administration’s “law and order” policies,1 congressional leaders have the opportunity to provide federal leadership on this issue through their funding choices. After all, the overwhelming majority of the country’s total incarcerated population—approximately 90 percent—is in state and local systems, not the federal system.2

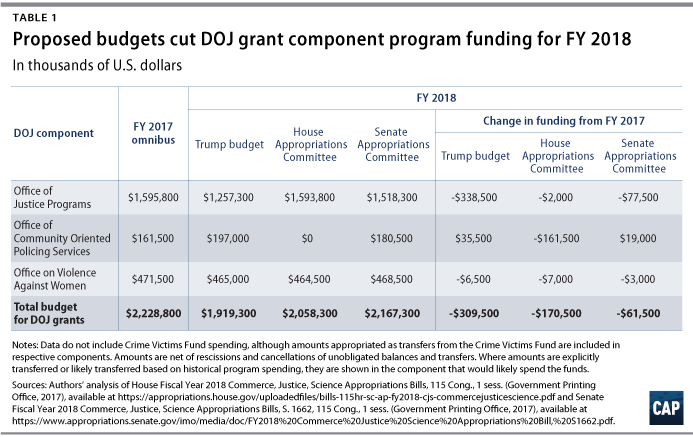

The House and Senate appropriations committees have marked up their respective appropriations bills, providing almost $2.2 billion for the DOJ’s discretionary grant programs for FY 2018.3 These grant programs represent the primary assistance that the federal government makes available to state and local public safety agencies each year. They also are one of the federal government’s main vehicle for supporting, enhancing, and in some cases influencing state and local criminal justice agencies.

The two appropriations bills are likely headed to a floor vote in September. The bills are different from each other, but both are certainly a dramatic improvement on the budget proposed by President Trump, which cuts DOJ’s discretionary grant funding by $310 million.4 Congress should ensure that funding priorities are aligned to address the critical and emerging criminal justice issues facing communities today. This issue brief examines four such important funding areas: 1) promote diversion into mental health and substance use treatment instead of incarceration; 2) reduce incarceration rates and levels; 3) eliminate the criminalization of poverty; and 4) increase support for indigent defense.

Promote diversion for mental health and substance use issues

The nation’s prisons and jails have become wards for many people dealing with mental health issues, substance use disorders, or, as is often the case, both. By recent estimates, 37 percent of prisoners and 44 percent of jail inmates have had mental health problems, including the 9 percent of prisoners and 12 percent of jail inmates with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders.5 At the same time, more than half of prison and jail inmates are drug dependent or have drug abuse disorders.6 These numbers are staggering, and the best option for many of these individuals is treatment, not incarceration. The White House Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis emphasized this conclusion, stating in its preliminary recommendations that President Trump’s top two action items should be to “[d]eclare a national emergency” regarding the opioid crisis and “rapidly increase treatment capacity.”7

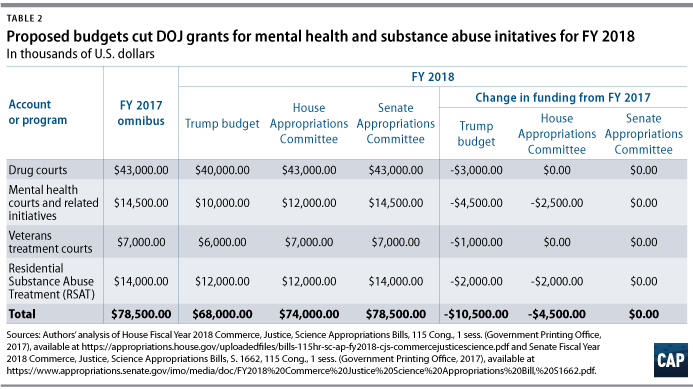

At the state level, many counties have implemented specialized court-based diversion programs, especially drug courts, although there are increasing numbers of mental health and veterans’ treatment courts as well. These so-called problem-solving courts provide opportunities for people charged with or convicted of crimes to receive treatment and specialized services to address the underlying issues that may have led to criminal activity. Upon completion of the treatment program, the person may receive a lower or deferred sentence, or not be charged with a crime at all.8 These court-based programs receive some support from DOJ grants; the FY 2018 House and Senate bills provide $62 million and $64.5 million, respectively.

While court-based programs help, the best diversion approaches may be those that aim to keep people out of the criminal justice system altogether. One of the criticisms of problem-solving courts is that treatment is not always successful, and failure or relapse can be punished with fines and jailing. Two promising strategies, Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) and the Police Assisted Addiction and Recovery Initiative (PAARI), rely on police to steer low level offenders and substance users to community-based services and treatment instead of prosecution and jail.9 Such initiatives are gaining law enforcement adherents, in cities such as Seattle; Santa Fe, New Mexio; Albany, New York; Gloucester, Massachusetts; and Portland, Oregon.10 Early research already has shown LEAD to be promising, with a 58 percent less likelihood of arrest following referral.11 DOJ has provided technical assistance to replicate LEAD, as well as a small amount of support for other potential mental health interventions.12 PAARI was cited by DOJ’s Office of Community Oriented Policing Services as a strategy that successfully addresses opioid use.13 These promising diversion programs can be replicated nationwide—and should be made a priority for DOJ grant funding.

Reduce incarceration

The U.S. criminal justice system imprisons people at a rate far exceeding the rates of virtually all other countries. Variously described as the result of the United States’ “War on Drugs,” harsh sentencing, and mandatory minimums, among other factors, incarceration has grown excessively since the 1990s.14 This has come at a tremendous cost, and not just because of the resources consumed by jails and prisons. In some states, spending for incarceration has outpaced funding for other important priorities, including higher education.15 Legislation, such as the Reverse Mass Incarceration Act, would change this historical funding pattern by pouring money back into states—$20 billion over 10 years—to incentivize states to reduce incarceration.16

While such legislation would certainly jumpstart federal leadership on criminal justice reform, incarceration has dropped by 13 percent from its peak in 2007-2008 in just a few short years.17 This is attributable in considerable part to the work of the Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI).18 JRI has been led and supported by organizations such as the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Council of State Governments Justice Center in partnership with the DOJ.19 The project involves specialized teams that work with state governors, legislators, corrections officials, and others to analyze the factors driving incarceration and propose reforms—many of which depend on passage of state legislation—to reduce incarceration without harming public safety.

JRI has tremendous bipartisan support. It received its first federal funding support due to the efforts of former Rep. Frank Wolf (R-VA), and since then, both Republican and Democratic legislators have embraced it. It also had the support of the Obama White House. Many of the states in which JRI has found its most fervent supporters have been led by Republican governors and legislatures, who have been keen on reducing unnecessary spending without compromising public safety.20

To date, JRI has received no more than $27.5 million per year in DOJ grant assistance.21 Despite the efforts of the Obama administration, which requested more than three times that amount in its FY 2014 budget, this level of funding represents the high-water mark for the project. In FY 2017, just $25 million is available for JRI.22 Neither the House nor the Senate FY 2018 CJS bill increases funding, and the Trump budget actually proposes cutting funding by 12 percent. The project deserves continuing, increased support, not just to consolidate and maintain the gains already achieved in reducing incarceration but also to accomplish much more.

Eliminate the criminalization of poverty

In the ongoing discussions and debates about criminal justice reform, much of the focus has been on reducing the size of the prison population. Recently, however, states have prioritized the reduction of jail populations. More than 430,000 people in U.S. jails have not been convicted of a crime and are awaiting trial, while 90 percent are there because they cannot afford to post a bond.23 Between 2000 and 2014, for example, 99 percent of the growth in local jail populations was the result of pretrial detention.24 This is an example of the criminalization of poverty—other forms of which have been ruled unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court.25

Current bail practices are not just an unfair and unnecessary penalty on poor defendants and defendants of color; they also burden taxpayers with costs.26 The Pretrial Justice Institute estimates that these pretrial detentions cost taxpayers $14 billion a year.27 This sum does not just represent waste—it is also a tremendous misallocation of state and local criminal justice system resources.

In July, Sens. Kamala Harris (D-CA) and Rand Paul (R-KY) introduced the Pretrial Integrity and Safety Act,28 which authorizes a new DOJ grant program. The grants would help states implement best practices for pretrial supervision without the use of a money bail system, hold states accountable for progress, and improve data on pretrial systems. The goals of this legislation must be supported as part of criminal justice reform efforts. The bill authorizes $15 million in annual grants, but congressional appropriators should consider higher numbers given the size and scope of the problem. Currently, there is no funding for bail reform in either the House or the Senate bill.

Increase support for indigent defense

The U.S. criminal justice system operates at its best when defendants have access to representation. This is a basic right established under the Sixth Amendment, but it took the 1963 Supreme Court ruling in Gideon v. Wainwright to achieve recognition that those unable to afford representation in criminal cases should have counsel appointed for them.29 Still, many states dramatically underfund indigent defense, often leaving the responsibility to localities, and representation remains unavailable in many places for misdemeanor and appellate matters.30 Burdening public defenders with unmanageable caseloads inevitably leads to instances of inadequate counsel for the criminally accused, sometimes with extreme results. Some clients may be encouraged to take plea deals when the evidence against them is insufficient.31 And ineffective counsel has been demonstrated to be at play in a high percentage of DNA exonerees’ cases.32

DOJ provides little financial support to improve indigent defense. The only grant specifically dedicated to this issue focuses on indigent defense for juveniles, and the amounts allocated to it are minimal. In FY 2016 and 2017, funding for juvenile indigent defense was $2.5 million per year. The Trump budget requested the same amount in FY 2018, while the House and Senate bills provide for $2 million.33 This lack of resources represents a tremendous misallocation of federal justice-related grant assistance. When DOJ grants overwhelmingly support police and police hiring, prosecutors, courts, and even prisons and jails but deprioritize public defenders and indigent defense systems, they help perpetuate the skewing of state and local funding priorities that makes it so difficult for many defendants to obtain adequate counsel. Thus, much more funding is needed to make indigent defense a bigger priority in both adult and juvenile justice systems.

Conclusion

This brief identifies four important areas where Congress should be looking to beef up funding as it finalizes its FY 2018 appropriations bills. Spending in these areas is one way that Congress can provide leadership to build a more effective criminal justice system and steer the country away from the Trump administration’s enthusiasm for traditional “law and order” approaches. Federal legislators can seize the issue of criminal justice reform and smart public safety measures to ensure that policies reflect the progress being made in many of the states they represent.

Mike Crowley is a former senior analyst specializing in justice issues with the Obama administration’s Office of Management and Budget. Ed Chung is vice president for Criminal Justice Reform at the Center for American Progress.