See also: Texas, Where Are the Judges? by Sandhya Bathija, Joshua Field, and Phillip Martin

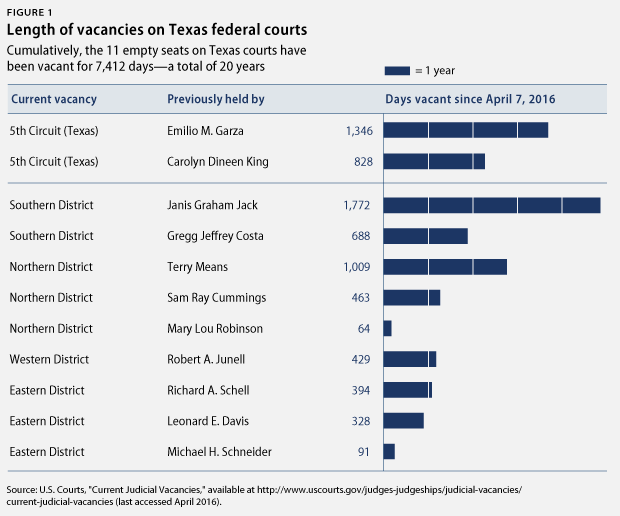

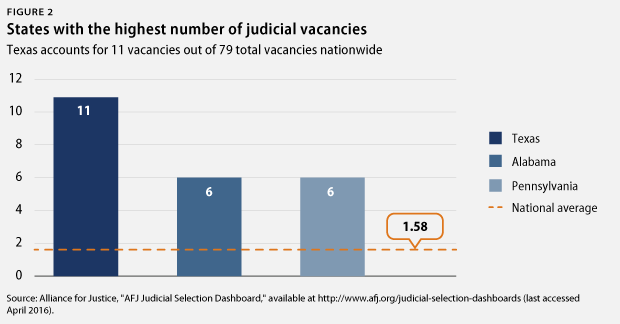

Just hours before President Barack Obama’s nomination of Judge Merrick Garland to the U.S. Supreme Court—and upon the recommendations of Texas’ two U.S. senators, Republicans John Cornyn and Ted Cruz—he nominated five judges for long-vacant seats on Texas’ federal courts. Given that Texas has more judicial vacancies than any other state in the nation—with 11 vacancies overall, including three federal court seats that have been empty for more than 1,000 days and a 12th future vacancy expected to become current soon—it is critical to Texans and to the judicial system as a whole that these five nominees receive swift consideration from the Senate.

Sens. Cornyn and Cruz, who both sit on the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, can play leading roles in ensuring that the process moves forward, but given their recent history, this does not seem very likely. Both Sens. Cornyn and Cruz have joined their Republican Senate colleagues in refusing to give Judge Garland a confirmation hearing, which does not bode well for the prospect of the five Texas judicial nominees receiving a hearing anytime soon. The Senate’s inaction on the nomination of Judge Garland is part of a pattern of obstructing judicial nominees, and nowhere does this practice play out more critically than in Texas.

In April 2014, the Center for American Progress, in conjunction with Progress Texas, produced the issue brief “Texas, Where Are the Judges?”, which highlighted the large number of vacancies in Texas federal courts and the impact of those empty judicial seats on Texans. The brief also highlighted the lack of diversity on Texas’ federal courts—a problem that has not been addressed in recent years.

Because judicial nominees depend on the support of their home-state senators to make it through the Senate confirmation process, the brief demonstrated how Sens. Cornyn and Cruz were pivotal in creating Texas’ judicial vacancy crisis. According to the brief, “Because federal benches are sitting empty in the Lone Star State, Texans cannot have their cases heard in a timely manner. Meanwhile, Texas federal judges and their staffs are overworked.” The brief urged the senators to set aside their partisanship disagreements with the president and work in the best interests of the people of Texas.

Today, some two years later and with the vacancies still a critical concern for justice in Texas, CAP has updated its earlier brief, which is even more relevant in light of the ongoing Supreme Court vacancy battle. Some Republican senators—Cornyn and Cruz included—are refusing to consider President Obama’s judicial nominees, and with a Supreme Court vacancy, the importance of lower federal courts is elevated. Since the death of Justice Antonin Scalia more than two months ago, the Supreme Court has issued two 4-4 decisions. Split decisions create no new Supreme Court precedent and uphold the lower-court rulings by default. This raises the stakes of the lower courts’ decisions and makes it all the more critical for senators to prioritize filling these lower-court vacancies as soon as possible.

Sens. Cornyn and Cruz should continue to do their jobs of helping fill Texas’ 11 federal court vacancies, including the two long-running vacancies on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit. What’s more, a 12th federal judicial vacancy is expected to open in Texas in the next few weeks. Fortunately, the senators already have suggested a nominee, but Sens. Cornyn and Cruz need to step up their pace and work with the White House to choose nominees for the remaining empty seats. They should work to recommend judges who add much-needed diversity to the bench. At the same time, they should hold their colleagues in the Senate leadership accountable and ask them to conduct hearings and hold votes for the five current nominees and Judge Garland.

Understanding the judicial process

A judicial vacancy occurs when a judge retires, steps down, or is otherwise unable to perform his or her duties. Future vacancies occur when a judge announces that he or she will be retiring from the bench or taking senior status—a part-time role indicating a judge’s intention to retire soon—by a certain date. Future vacancies matter because the moment a judge announces he or she will be retiring at a future date is the same moment that the president and senators can begin to work on filling that judge’s seat. Ideally, a new judge has been nominated and confirmed by the time the retiring judge leaves the bench to create a seamless process for keeping federal benches filled. A judicial emergency occurs where there are not enough judges to hear the cases that are piling up on the docket.

Home-state senators play a key role in every step of the process. The president nominates a judge, usually following a recommendation from home-state senators. The same two senators are then responsible for submitting blue slips of paper to demonstrate their approval. The Senate Judiciary Committee then holds a hearing and a vote. If approved, there is a confirmation vote by the entire Senate. The Senate determines how quickly, if at all, the president’s nominee moves through the confirmation process.

Denying Texans access to justice

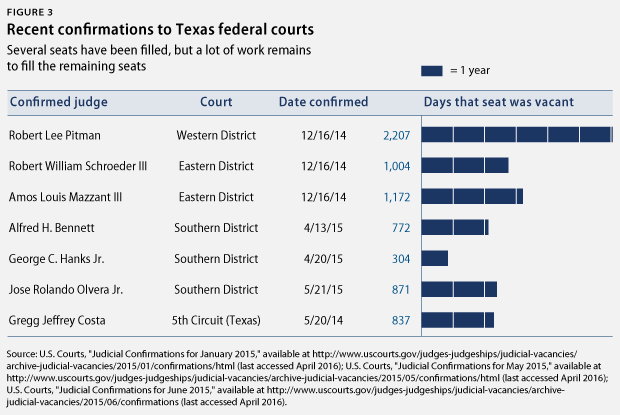

As of April 7, 2016, the 114th Congress has confirmed three Texas judges to the federal bench, with the most recent confirmations taking place in May 2015. There are nine current district court vacancies in Texas, seven of which opened up since CAP’s previous brief in April 2014. Additionally, Judge Jorge Antonio Solis’ seat on the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas will become vacant in May 2016—bringing the total number of district court judicial vacancies in Texas to 10. In addition to the district court vacancies, there are two long-running circuit court vacancies. Of the 12 current and future judicial vacancies, nine have been classified as judicial emergencies—an official designation for courts severely overburdened because of judicial vacancies.

As of April 7, a cumulative 2,174 days have passed since the two seats on the 5th Circuit became vacant. Both 5th Circuit vacancies are also judicial emergencies.

Texas has the most vacancies on its federal courts of any state in the country, with no other state even coming close. Alabama and Pennsylvania, with the next highest number of vacancies, have six empty seats each.

Texas also claims an alarming 32 percent of all judicial emergency vacancies. This percentage is vastly disproportionate to the state’s 8.14 percent of the national population.

Unprecedented obstruction means delayed justice

The 5th Circuit has jurisdiction over Texas, Mississippi, and Louisiana. In 2014, there were 7,765 cases filed with the 5th Circuit, but 4,638 pending appeals were left unresolved—creating an enormous backlog. As federal benches sit empty in the Lone Star State, the courts remain overworked. This means that countless Texans and Texas businesses have not had their cases heard in a timely manner. Not having judges on the bench has substantial, real-world consequences for tens of thousands of Texans.

Why these numbers matter

Such an enormous backlog on the dockets of federal courts keeps families and businesses from obtaining the justice they need and deserve—from a low-wage worker suing her employer for wage theft to an indigent defendant unable to afford bail spending months behind bars waiting for a day in court.

In Sherman, Texas, for example, a lawyer recently represented a client who, the lawyer feared, would languish in jail waiting for a trial, watching as her co-defendants pleaded guilty and finished their terms before her case was even heard. Delays in court can mean that innocent people are pressured to take plea bargains just to get out of jail. Judicial vacancies also have also made “a huge difference in how the prosecution looks at cases,” the attorney said. “[Prosecutors] tell you your client will be in jail because [her co-defendants] took a plea and she wants a trial … It’s a hammer over her head—plead guilty and you’ll be out of jail.” The Constitution guarantees the right to a speedy trial, but felony trials must work their way through crowded dockets.

In addition to those involved in the justice system, judicial backlogs have a real and tangible effect on the lives of all Americans. For example, a 2015 independent study estimated that filling the two vacancies in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas alone would create nearly 78,200 jobs and a net economic benefit of about $11.7 billion by 2030 in the district.

Some progress in Texas but not nearly enough

From May 2014 to April 2016, Texas saw six district court confirmations and one 5th Circuit confirmation. While this is progress when it comes to filling empty seats, there is still no getting around the fact that those seats remained vacant for several years—simply put, way too long.

Sens. Cornyn and Cruz should prioritize filling Texas’ remaining 11 vacancies in a timely manner by strongly advocating for a hearing and a vote on their five nominees. Moreover, they must work to identify nominees for the seven remaining vacancies in Texas.

The reality, however, shows a national federal judicial landscape of widespread obstruction by Senate leadership. Of the 27 states with current judicial vacancies, 14 are represented by two Republican senators, while only eight states have two Democratic senators. Six more states are split between the two parties—one Democratic senator and one Republican senator. Until all senators work together, across the aisle, to fill the federal courts with qualified jurists, access to justice will remain problematic for the millions of Americans in regions with judicial vacancies.

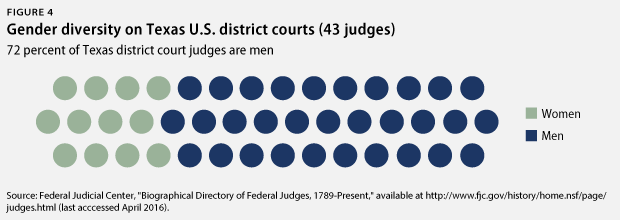

Racial and gender diversity suffers on the federal bench in Texas and elsewhere

Diversity on the bench is immensely important. Judges with a variety of backgrounds—different races, genders, and professional and life experiences—bring their varying and unique perspectives to the bench. This is important when it comes to bringing an understanding of how the law may operate differently for different groups of people, as well as of the effect that a court decision may have across swaths of the American public. The courts are tasked with ensuring equal justice under the law, and a diversity of judicial perspectives helps ensure that the Constitution works for everyone. However, the Texas federal judiciary fails to reflect the diversity of the state’s population.

As Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg has said on a number of occasions, “[T]here are life experiences a woman has that come from growing up in a woman’s body that men don’t have.” For example, Justice Ginsburg has said that perhaps female judges bring “a little more empathy” to the bench because “anybody who has been discriminated against, who comes from a group that’s been discriminated against, knows what it’s like.” Moreover, an empirical analysis found that although plaintiffs mostly lost in cases involving sexual harassment and sex discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, they were “twice as likely to prevail when a female judge was on the bench.”

Despite the importance of female judges, in Texas, women on the bench are few and far between. While more than half of the population of Texas is female, less than one-third of Texas’ federal judiciary is female. There are only 16 female federal judges on the Texas district courts out of a total of 64 active and semi-retired judges. Sens. Cruz and Cornyn, after not putting forward a woman for a federal judgeship in more than four years, have now included two female judges—U.S. Magistrate Judge Irma Carillo Ramirez and former Texas State District Judge Karen Gren Scholer—in their five nominees to the president. Now the senators must work to ensure that these nominees receive a fair hearing and a timely vote.

The picture for racial diversity on Texas’ district courts is slightly more nuanced. Compared with the numbers on gender diversity, the percentage of African American and Hispanic judges on Texas’ courts is closer to that of the Texas population as a whole. In Texas, the population is 44 percent white, 38.4 percent Hispanic, and 12.4 percent black. Out of a total of 64 active and semi-retired district court judges, there are 42 white judges at 66 percent; 17 Hispanic judges at 27 percent; and 5 black judges at 7.8 percent. The confirmation of Judge Ramirez would bring the percentage of Hispanic judges closer to parity with the population of Texas.

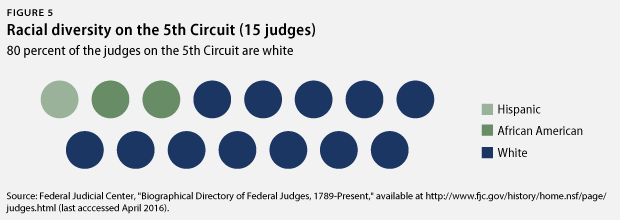

However, racial and ethnic diversity is sorely lacking on the 5th Circuit, and Sens. Cornyn and Cruz have yet to work with the president to fix this problem. Eighteen of the 22 active and semi-retired judges—82 percent—are white, even though whites account for less than half of the population of the three states—Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi—in the circuit. Around 17 percent of this population is black, but only two black judges sit on the 5th Circuit. Just two of 22 judges on the circuit are Hispanic, even though Hispanics account for 31 percent of the circuit’s population. These stark discrepancies illustrate the critical need to take diversity into account when filling 5th Circuit vacancies, including the two vacant Texas seats.

Some judges on the 5th Circuit have found themselves embroiled in controversies that some critics argue reveal a racial bias. For example, in February 2013, 5th Circuit Judge Edith Jones spoke at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, where she allegedly, according to sources, stated that African Americans and Latinos are “predisposed to crime.” In response, a coalition of civil rights groups and professors filed a judicial misconduct complaint, arguing that her remarks indicated a lack of impartiality and violated several canons of the Code of Conduct for federal judges. These types of occurrences and the reality that they portray to the public hurt not only the 5th Circuit’s neutrality and fairness in handing down decisions but also the legitimacy of those very decisions and the 5th Circuit itself.

The vacancies on the district courts and 5th Circuit provide an opportunity for Sens. Cornyn and Cruz to show a true commitment to broadening the scope of who sits on the bench by recommending qualified judges who mirror the population of Texas.

Rulings from the politicized 5th Circuit headed to the Supreme Court

Many in the legal community consider the 5th Circuit Court the most conservative and ideologically driven court in the country. A 2014 article in the ABA Journal called it “one of the most controversial, rancorous, dysfunctional, staunchly conservative and important appellate courts in the country.” The article noted that the 5th Circuit has sometimes exhibited an “unpleasant undercurrent” stemming from incidences of racially charged remarks and personal jabs between judges.

The 5th Circuit has issued extreme opinions on abortion, voter ID laws, and the death penalty, and it has a strong pro-business record. In fact, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce has filed amicus briefs in more than a dozen cases in the 5th Circuit since 2007, and the court has ruled in the chamber’s favor in 79 percent of those cases, including rulings involving the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

A number of the sitting 5th Circuit judges have ties to the energy industry. When a lawsuit by the victims of Hurricane Katrina against fossil fuel polluters made its way to a full 5th Circuit panel in 2013, there were not enough judges available to hear the case because so many had to recuse themselves due to a conflict of interest. The result was a disaster for victims of Hurricane Katrina and a victory for the energy industry, according to a report from the Alliance for Justice, a nonprofit membership organization dedicated to ensuring a fair and just judiciary.

These conservative, pro-business rulings often have implications beyond the 5th Circuit itself. According to Edward Blum, director of the Project on Fair Representation, the group that brought redistricting and affirmative action cases to the Supreme Court this year, “[A]dvocates wishing to bring litigation that will result in high-profile, conservative outcomes ha[ve] incentive to go to the 5th Circuit.” Additionally, many of the decisions coming out of the 5th Circuit have unwound critical precedents. In some instances, a bad decision from the 5th Circuit has been the lone cause of a circuit split, when the 5th Circuit has strayed from the legal interpretations accepted by its fellow circuits.

Given this environment, it is perhaps not surprising that the Supreme Court is reviewing a disproportionate number of 5th Circuit rulings in 2016. The Court is reviewing Whole Woman’s Health v. Cole, a case out of the 5th Circuit in which Republicanappointed judges upheld provisions of a Texas law that imposes medically unnecessary restrictions on abortion facilities, resulting in the closure of many of the state’s clinics. Three 5th Circuit judges not only upheld provisions of the law that would result in clinic closures in a series of decisions, but they also went out of their way to ensure that the clinics would close as soon as possible. On October 31, 2013, another three-judge panel unanimously granted the state an emergency stay that allowed the law to shutter clinic doors even while it was still being challenged in court. The challenged provision of the statute requires abortion clinic doctors to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital, a medically unnecessary requirement that is often impossible to meet, since hospitals can use political reasons to reject applications for admitting privileges.

How a case reaches the Supreme Court

Typically, a case reaches the Supreme Court in one of two ways. Some state cases may be appealed directly from a state supreme court if they involve federal law. Cases in the federal courts typically must work their way from a federal district court, where trials are held, to a federal appellate court and then can be appealed to the Supreme Court. There are some instances in which the Supreme Court may be more likely to take a case than others. For example, if a case involves an issue that has created a circuit split—meaning that circuit courts have ruled in different ways on the same legal question—the Court typically is more likely to take the case to resolve the dispute. But the Court always has the final say on which cases it hears. Although about 1,000 cases are appealed to the Supreme Court every year, it typically only decides about 75 cases.

In June 2015, after upholding the Texas law’s admitting privileges requirement, the 5th Circuit upheld a second provision of the Texas law that requires abortion providers to meet the same building standards as hospitals. The state argued that the law safeguards women’s health, but in reality, these standards do nothing to protect women’s health or safety. Abortion facilities would be required to undertake expensive and unnecessary building changes such as widening their hallways and installing equipment that is never used during an abortion procedure. Texas required one clinic to change the color of the paint on its walls and install emergency medical equipment that it never used. Nonetheless, the 5th Circuit accepted the state’s argument. Decisions that close clinic doors unnecessarily devastate women. In fact, a recent study found that women were forced to travel four times farther to an abortion clinic, often could not get the medication abortion they wanted, and faced at least three unnecessary hurdles to obtaining an abortion.

Even as the 5th Circuit acted quickly to close Texas abortion clinics, it moved at a glacial pace in making a decision on President Obama’s immigration directives—Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents, or DAPA, and an expansion of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA. An article that appeared in The New York Times suggested that the delay was a tactic to lessen the case’s chances of reaching the Supreme Court this term, arguing that the delay rings of “political behavior that is unconscionable for a federal court.” And when the 5th Circuit finally decided the case 2-1, the judges blocked the policies from going into effect. The dissenting judge, Carolyn Dineen King, concluded her opinion by confirming the unacceptable delay: “I have a firm and definite conviction that a mistake has been made. That mistake has been exacerbated by the extended delay that has occurred in deciding this ‘expedited’ appeal. There is no justification for that delay.” The ruling has left in limbo about 4 million parents and children who would have been eligible for deferred action under the policies, as well as 6.1 million U.S. citizen relatives who live in the same household as one of these immigrants.

The Supreme Court has strongly rebuked the 5th Circuit on several occasions. In 2008, Robbie Tolan—a budding professional baseball player in Texas—was shot three times by a police officer outside his home after the officer incorrectly identified Tolan’s car as a stolen vehicle. Tolan survived the shots but was left with a life-altering injury that ended any chance of a professional baseball career. The federal district court found that the officer’s use of force was not unreasonable, and less than a month later, the 5th Circuit upheld the district court’s decision. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court reversed the 5th Circuit. The Court essentially found that the 5th Circuit worked backward from its own conclusion, saying that it “fail[ed] to credit evidence that contradicted some of its key factual conclusions.” Even Justice Samuel Alito, who many view as “the most pro-prosecution Justice on the Court,” wrote separately but agreed that the 5th Circuit should be overruled.

In 2015, the Supreme Court again reversed a 5th Circuit decision that raised the question of when a criminal defendant is entitled to a hearing to determine whether, under the Constitution, he is too intellectually disabled to be executed by the state. The federal district court found that the defendant, whose IQ was around 65 or 70, had “significantly limited conceptual skills,” which made him ineligible for execution. The 5th Circuit reversed this ruling and deferred to a state court decision that would have allowed the defendant to be executed without a hearing on his intellectual disability. The Supreme Court overruled the 5th Circuit, stating that its decision was “based on an unreasonable determination of the facts.”

Now, with a vacancy on the Supreme Court resulting from the death of Justice Scalia and only eight justices to decide critical cases, the 5th Circuit’s decisions loom ever more important. Typically, with a full nine-member Supreme Court bench, only a majority of the Court could decide to uphold the 5th Circuit’s decisions. But with an eight-justice Supreme Court, there are now two ways that the Court may uphold the 5th Circuit: by a majority vote or by a tied vote. If the Supreme Court votes 4-4, the lower-court decision— the 5th Circuit in these instances—is upheld by default. Therefore, filling the vacancies on the 5th Circuit now with exceptionally well-qualified and diverse nominees is critical.

Changes on the border: The Western and Southern districts

Progress has been made on the vacant judgeships in the Texas districts that serve the U.S.- Mexico border, an area with a particularly large caseload. The Western and Southern districts serve some of the fastest-growing populations in the country, and their dockets have been swollen by drug and immigration cases. As noted in CAP’s 2014 report, the five federal judicial districts along the southwest border—which include Texas’ Western and Southern districts that serve El Paso, San Antonio, and Laredo—“accounted for 56 percent of all federal suspects arrested and booked in the U.S. and 90 percent of all immigration arrests in 2010” and “handled the largest number of felony cases per judge in the federal criminal court system,” according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

With so many cases involving immigration issues, backlogs in the Western and Southern districts pile up. As they do, immigrants and their families often remain in legal limbo, waiting for their day in court. A recent article in The Dallas Morning News looked at the immigration court experience of Jeong-Seok Kang, who is from South Korea but lived for years in Dallas. Although his visa has expired, Kang’s attorney says he is eligible for permanent residency because his wife recently obtained a green card and he lacks a criminal record. According to the article:

Kang has been in America long enough to raise two sons and run a family-owned doughnut shop in Irving. After years of worrying, he thinks he’s about to find out his fate. Things look promising. But Sims sets a merit hearing for Dec. 6, 2017. Kang is caught in an immigration court system that is bursting with huge caseloads and stressed by a seemingly endless shortage of judges.

All three judges confirmed in 2015 were from the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas, but there are still three vacancies remaining across the Western and Southern districts. As of April 7, 2016, these seats have sat empty, collectively, for more than 2,880 days, or nearly eight years.

Currently, there is only one pending nominee for three vacancies in the Western and Southern districts. Even if some of these vacancies are filled, it will take time to work through the existing backlog of cases in these courts.

Conclusion

The framers of the Constitution intended the judicial branch to be an independent arm of the government, tasked with protecting the rights of individual citizens throughout the country. Yet when judicial seats sit empty for days, months, or years—as they have in Texas—justice suffers everywhere. The judicial vacancy crisis in Texas is harmful to the very foundation of our nation’s judiciary. It is even more harmful in light of the current vacancy on the Supreme Court, which has and could continue to uphold lower-court decisions by failing to reach a majority decision and deadlocking with a 4-4 tie. The American people—especially those who live in states where the law is affected by the vacancy on the Supreme Court and those waiting for and denied their day in court because there are too few federal court judges—cannot wait any longer to have judicial vacancies filled. In no place is that more true than Texas.

Texans, like Americans everywhere, value their constitutionally protected access to justice, yet Texas continues to hold the record for the highest number of judicial vacancies in the country. CAP’s April 2014 brief said, “Sens. Cornyn and Cruz must put their constituents above political gamesmanship and end their unwavering obstruction of the federal judicial nomination process.” Now that they have worked with the White House on five nominees, the two Texas senators should continue doing their jobs and push for a hearing and a vote on these nominees.

It is critical that the Senate hold an up-or-down vote on these exceptionally well-qualified pending judicial nominees. Simultaneously, Sens. Cornyn and Cruz should work with the president to fill remaining vacancies, including the crucial seats on the 5th Circuit and the Supreme Court. Only when this judicial crisis is remedied can Texans be assured that their constitutionally guaranteed access to a fully functioning and fair judiciary is protected.

Anisha Singh is the Campaign Manager for Legal Progress at the Center for American Progress. Abby Bar-Lev is a Policy Analyst for Legal Progress. Phillip Martin is the deputy director of Progress Texas, based in Austin.

The authors would like to thank their friends at the Alliance for Justice, particularly Nathaniel Gryll, for their assistance fact-checking this issue brief and their attention to these important issues. They also would like to thank their colleagues at the Center for American Progress: Billy Corriher, Michele Jawando, Jake Faleschini, Tanya Arditi, former Legal Progress interns Maya Efrati and Maheen Ahmed, and the entire Art and Editorial teams.