The U.S. Supreme Court grabbed headlines in late November when it announced that it would hear two cases concerning whether for-profit corporations whose owners are opposed to providing contraceptive coverage to their employees in compliance with the Affordable Care Act are “persons” entitled to exercise their religious liberty. The cases—Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. v. Sebelius and Conestoga Wood Specialties Corp. v. Sebelius—along with others that rely on claims of religious liberty to avoid following the law, are a crucial element of a widening debate that has far-reaching implications about religious liberty, fairness, and equality.

The states, in particular, have become a focus of policy battles involving progressive initiatives and religious liberty in recent years. Recent victories on marriage equality, for instance, have triggered a conservative backlash that is using religious liberty as a cover to push back against these victories and turn back the clock. The truth is that religious liberty is not in conflict with marriage equality or with women’s reproductive rights. But opponents are claiming a conflict in an attempt to gain public sympathy and support for what would otherwise be unpopular positions.

Religious liberty is a core American value. Furthermore, the vast majority of Americans know that this core value is not hanging by a thread, despite conservative claims. Americans recognize the need to negotiate concerns about religious liberty in a pluralistic democracy where there are many different beliefs with sometimes competing claims in order to ensure fairness and equality for all Americans. Moreover, a majority of the public believes that our existing laws strike the right balance and that there is no need for new laws or overly broad loopholes and exemptions that could result in discrimination and undermine a wide variety of laws and regulations wholly unrelated to the exercise of religion.

This issue brief focuses on the recent history of the religious liberty debate, the current state of play in states across the country, and the threat to progressive values and accomplishments posed by exceedingly broad religious liberty exemptions that open the door to discrimination.

In many ways, the religious liberty debate at the state level was set in motion by a series of events in the 1990s, including two high-profile Supreme Court cases and a landmark federal law.

Two decades ago this past November, Congress almost unanimously passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, or RFRA. The act is a short law meant to ensure that laws that potentially infringe on the free exercise of religion under the First Amendment to the Constitution are reviewed by courts under so-called “strict scrutiny”—the highest bar for achieving constitutionality.

The law states that “[g]overnment shall not substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion even if the burden results from a rule of general applicability.” Nevertheless, laws or government actions can still pass muster under RFRA if they are both in “furtherance of a compelling governmental interest” and “the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest.”

The broad, bipartisan effort to pass RFRA came in the wake of a 1990 decision by the Supreme Court in the case of Employment Division v. Smith. The high court found that “a person’s religious beliefs cannot prevent him or her from abiding by laws that are neutral and not aimed at restricting religious freedom,” thus lowering the level of scrutiny necessary for laws to pass constitutional muster.

The opinion, written by conservative Justice Antonin Scalia, concerned two members of the Native American Church who were fired from their jobs as drug counselors after using the illegal drug peyote in a religious ritual and were subsequently denied unemployment compensation by the state of Oregon.

“To permit this would be to make the professed doctrines of religious belief superior to the law of the land, and in effect to permit every citizen to become a law unto himself,” Scalia wrote.

A second major Supreme Court decision, City of Boerne v. Flores, struck down RFRA as applying to states and localities on the ground that Congress had exceeded its authority under the 14th Amendment. The 1997 decision left RFRA in place at the federal level.

State-level religious liberty measures

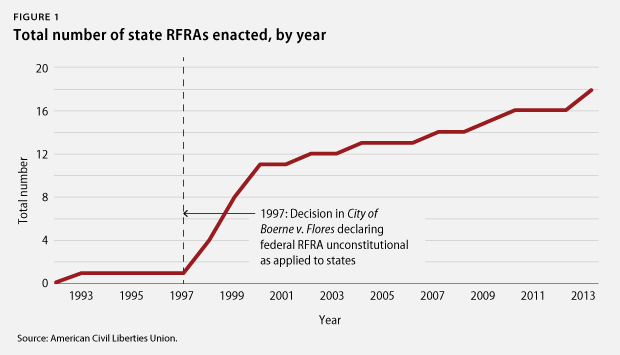

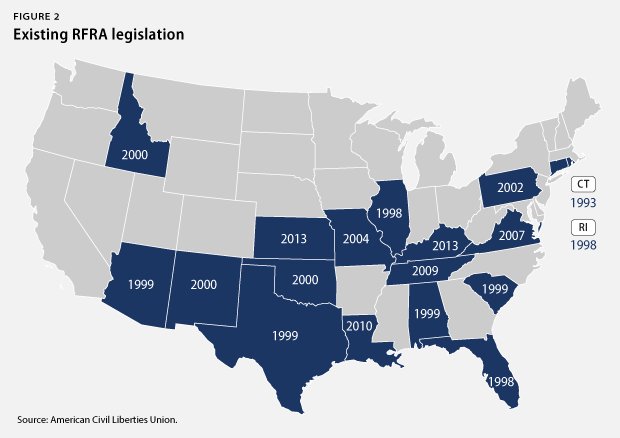

Prior to the decision in City of Boerne v. Flores, just one state—Connecticut—had passed its state-level RFRA in 1993. After the decision, a number of states did so. Within three years of the decision, 11 states, including Illinois, Florida, and Texas, had passed their own version of an RFRA.

As of 2013, a total of 18 states have enacted some kind of state-level RFRA, with Kansas and Kentucky being the two most recent states to do so. The Kentucky statute, passed in March 2013 after the legislature overrode the veto of Gov. Steve Beshear (D-KY), would protect discrimination based merely on the ill-defined and vague term “sincerely held religious beliefs.” Compared to the federal RFRA, state-level RFRAs often include broader and more problematic language and raise additional concerns because they may also undermine existing state civil rights protections that are broader than those found in federal law.

The past two years have also witnessed a profusion of new measures introduced in states across the country. Other states that already have legislation on the books, such as Texas and Arizona, have seen additional legislation introduced that would greatly expand the scope of their existing religious liberty laws. Take, for example, multiple proposals introduced in Texas that would expand the religious exemptions in the state’s existing RFRA by eliminating the “substantial burden” test. It would further expand the scope of the Texas law by adding even indirect burdens on religious exercise to potential causes of action.

In addition, an organized coalition comprised of conservative evangelicals, the Catholic bishops, Mormons, Orthodox Jews, and others are engaged in a campaign to claim a monopoly on religious liberty, to set it in opposition to civil rights and women’s health issues, and to claim persecution based on their refusal to follow the law. Their redefinition of religious liberty so that it would apply only to them would impose their particular theological views on a diverse public, trample on the religious liberty of others, and threaten basic constitutional rights and freedoms. A few recent examples of these efforts at the state level include:

- Under heavy pressure from the Catholic hierarchy and others, Maine voters overturned marriage equality legislation via referendum in 2009 (which was then reinstated via referendum in 2012).

- In 2010, Iowa voters removed three of the Iowa Supreme Court justices who had backed the court’s unanimous 2009 decision in favor of marriage equality after a religious liberty-focused campaign by right-wing activists. Voters chose to retain another justice targeted by the same activists in 2012.

- North Carolina voters approved a constitutional amendment banning marriage equality in 2012, the state’s first constitutional provision regarding marriage since it enacted a ban on interracial marriage in 1875.

- Minnesota voters rejected a constitutional ban on marriage equality in 2012. (Marriage equality was enacted legislatively in 2013.)

- North Dakota voters overwhelmingly rejected a “religious liberty restoration” amendment to its state constitution in 2012.

- Colorado voters overwhelmingly rejected radical “personhood” measures—which define a fertilized egg as a full-fledged human being—in 2008, and again in 2010. The issue will go to a vote again in 2014. Mississippi voters also soundly rejected a personhood amendment in 2011. The issue has also cropped up in numerous other states, including Oklahoma, Arkansas, Montana, Wisconsin, Florida, Ohio, and North Dakota.

- Last month, voters in Albuquerque, New Mexico, rejected the first-ever attempt to restrict late-term abortion at the municipal level, an effort championed by the anti-abortion group, Operation Rescue.

Finally, the scale and scope of religious exemptions has often been one of the final points of contention in successful marriage equality efforts in states across the country.

Dangerously broad impact

The First Amendment to the Constitution contains two parts—the free exercise clause, which allows people to freely exercise their faith, and the establishment clause, which forbids the government from interfering with religion or advancing any particular religion. Both offer broad protections to clergy, houses of worship, people of faith, and the general public. In addition, state constitutions and other existing laws offer sweeping protections for individuals, religious institutions, and religious organizations. These protections make new laws that promise to guarantee religious liberty either unnecessary because they replicate existing laws, or are dangerous and potentially unconstitutional because they go beyond constitutional guarantees to play favorites with certain theological beliefs. Many of the measures being advanced in the name of religious liberty go far beyond any reasonable balance between the religious liberty of some individuals and the rights, religious liberty, and freedoms of others. Indeed, some measures would codify discrimination in the name of conscience, unfairly privilege the religious views of a few over the religious and nonreligious views of others, and undermine many important laws and protections that have nothing to do with religion or social issues.

Our shared American values and simple fairness dictate that a person or institution cannot simply pick and choose which laws they want to follow and which they want to ignore. But that is precisely what many vaguely worded and overly broad measures invoking religious liberty would allow. Worse yet, some of these measures would make it legal for businesses and organizations—including those that receive taxpayer funds—to disregard existing civil rights laws, including those dealing with employment, housing, and public accommodation, without legal consequence.

Sally Steenland, Director of the Faith and Progressive Policy Initiative at the Center for American Progress, recently spelled out what these efforts come down to at their core:

Right now there are lawsuits in several states that are pertinent to this debate. They range from a baker in Oregon and a florist in Washington state to a photographer in New Mexico, all of whom refused to serve gay or lesbian couples because of religious objections to their wedding and marriage.

Let’s be clear about what these businesses—and their activist supporters—want. They want religious exemptions that will trump existing civil rights laws. They want to be able to legally discriminate against gays and lesbians in the name of religion. In their view, florists, bakers, caterers, jewelers, photographers, wedding-dress shop owners, tuxedo-rental owners, and a host of other commercial establishments should be able to turn away gay and lesbian couples without getting sued for discrimination.

Religious liberty means religious liberty for everyone. And that includes the freedom from having the theological doctrines of your boss or those of business owners in your community being forced upon you.

Despite the fact that the Supreme Court claimed in Citizens United that corporations have free speech rights—and may rule in the Hobby Lobby case that the free speech rights of corporations include religious liberty, the fact is that corporations are not human beings—they have neither bodies nor souls and were never intended in existing law, the Constitution, or common sense, to possess religious liberty. As my Center for American Progress colleagues Julia Mirabella and Sandhya Bathija recently wrote:

- History and the law recognize religious-freedom protections only for individuals and nonprofit, religious entities.

- A corporation and its owner are two different entities in the eyes of the law.

- Congress never intended for corporations to have religious-freedom rights under the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act, the law under which the plaintiffs in the case are bringing suit.

Should the Court err in the Hobby Lobby case and rule that corporations have religious liberty, the harmful consequences are difficult to overstate. For instance, for-profit businesses could argue that they can refuse to obey basic civil rights laws covering employment, housing, pregnancy discrimination, and public accommodation, to name but a few. As Mirabella and Bathija note, this could lead to the elimination of civil rights protections at the state level, even in states where it might be difficult to imagine such efforts succeeding legislatively or at the ballot box. Once the legal precedent is set, business owners who do not want to follow certain laws would have this legal loophole on their side.

What’s more, for-profit corporations could choose to proclaim a religious identity in order to disregard laws wholly unrelated to the free exercise of religion simply for the purpose of gaining a competitive or financial advantage. Some religious institutions, for example, currently offer pension plans that are exempt from federal protections, which has left some workers completely exposed when these noninsured plans run into trouble or are underfunded. Under the legal theory being advanced by Hobby Lobby and others, for-profit corporations could seek similar exemptions to pension laws and other workplace protections and regulations under the guise of religious liberty. The potential consequences for employees and consumers are staggering. This theory also raises troubling questions about corporate governance.

Severe consequences

For women and their families especially, the consequences of personhood measures pushed by activist groups on the religious right are sweeping. Not only would such laws ban abortion under all circumstances, but they could also outlaw common forms of birth control, including the pill and fertility treatments such as in vitro fertilization. Such a law unfairly favors one set of theological doctrines above others. For instance, most major religions view contraception and family planning as a moral good. The New Evangelical Partnership for the Common Good released a report in 2012, titled “A Call to Christian Common Ground on Family Planning, and Maternal and Children’s Health” that spelled out the religious and health benefits of family planning. The vast majority of Catholics disagree with the bishops about the morality of birth control. And most Americans, religious and nonreligious, along with scientists and medical experts, agree that while one may believe that a zygote equals a human being, to confer full constitutional and legal rights on that zygote should be a matter of faith and not law. Even other less-extreme conscience measures, such as pharmacists refusing to stock or fill prescriptions for contraception or hospitals refusing to perform life-saving abortions, also chip away at access to birth control and other basic health care services, restrict or deny access to the constitutionally protected right to have an abortion, and place women’s health in danger.

Some religious refusal measures are so far-reaching that, were they to become law, could override many existing vital laws. Last year’s successful campaign against North Dakota’s Measure 3, the state’s so-called “Religious Liberty Restoration Amendment,” for example, featured experts warning that the “dangerous” ballot measure could “make it harder to prosecute abusers” by allowing men to claim that it was their “sincerely held religious belief ”—the vague standard set out in Measure 3 and similar proposals—that they be allowed to discipline their wife and children as they see fit. A former judge and prosecutor warned that it could impact laws governing child neglect, minimum wage, and workplace discrimination. A doctor explained that she could be “prevented from providing life-saving care,” including to children.

Americans agree that existing religious liberty protections offer the right balance

If the bad news is the scale and scope of the threat posed by so-called religious liberty efforts cropping up in states and court rooms across the country, then the good news is that Americans overwhelmingly support nondiscrimination laws and “voters know that our laws and the Constitution already robustly protect religious liberty,” according to Third Way and the Human Rights Campaign.

A poll released earlier this year by Third Way and the Human Rights Campaign found that:

- Sixty-seven percent of voters agreed with the statement that “our laws already strike the right balance when it comes to religious liberty and small business, and we should not change that.”

- Sixty-nine percent of voters agreed that private businesses should not be allowed to refuse to provide products or services to gays or lesbians regardless of their religious beliefs. (Sixty-eight percent, including 75 percent of Independents, 55 percent of Republicans, and 68 percent of Christians, said the same when asked specifically about small businesses.)

- Nearly two-thirds of Americans also believe that businesses should not be allowed to deny wedding-related services to gay and lesbian couples because of a personal religious objection.

- By huge margins, Americans also believe that people such as doctors, accountants, caterers, and florists should not be allowed to refuse to serve gay people and couples.

Americans also agree that a house of worship or clergy member should not be required to perform a same-sex marriage, but this is a protection that churches and clergy already enjoy under the First Amendment and the marriage equality laws passed in states across the country. A majority of Americans back marriage equality and even more agree that legalizing discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender, or LGBT, people is wrong. Similarly, birth-control bans and measures that weaken protections for children and undermine our most fundamental civil rights laws are not winning issues. In fact, they have lost at the ballot box even in conservative states such as North Dakota and Mississippi.

Because opponents of progress are losing on the merits of the issues, they have shifted their strategy. Instead of basing their arguments on their opposition to marriage equality or contraception, they have grabbed onto religious liberty and are weaponizing it in their fight against justice and equality. In so doing, they are setting up a dangerous and false choice between equality and religious liberty. Conservative “activist opponents see their last, best defense as creating overly broad religious exemptions that will permit them to ignore laws they disagree with, all the while claiming persecution because of their beliefs,” writes Steenland.

Progressive values are mainstream American values. That is why it is incumbent on progressives to expose the stealth efforts of our opponents who are trying to roll back hard-fought victories and protections. Conservatives want the debate to be framed around “conscience versus convenience,” in which they can claim the moral high ground. But the real debate—and one progressives can win—is about our shared American values of fairness, tolerance, and equal protection under the law.

Joshua Dorner is the Communications Director at the Center for American Progress.