This report is the first in a series on different policies that could help mitigate the influence of corporate campaign cash in judicial elections. The reports are intended for advocates or legislators who want to ensure our justice system works for everyone, not just those with enough money to donate.

As this year’s election approaches, political attack ads are flooding the airwaves, fueled by unprecedented sums of money from corporations and wealthy individuals funding “independent” political ads. Much of the money is funneled through nonprofit organizations that do not disclose their donors.

In August 2012 the Center for American Progress issued a report on how campaign donations from big business have come to dominate judicial elections, resulting in courts that favor corporations over individual citizens. Our new report concludes with recommendations for strong rules that require reporting of all ads that mention candidates, including information on those who gave money to independent spenders. States should also respond to Citizens United by requiring corporations engaged in political spending to disclose that information to their shareholders.

Although disclosure laws usually apply to elections for all branches of government, these recommendations were made specifically with judicial campaigns in mind. Judicial elections involve unique interests that make the need for transparency in campaign finance even greater than in other elections.

In a series of cases striking down campaign finance reform laws, federal courts have opened the door to unlimited political spending by ostensibly “independent” groups. The U.S. Supreme Court in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission overruled a 1990 case that thwarted an attempt by the Michigan Chamber of Commerce, a nonprofit corporation under Michigan law, to spend its general treasury funds on political ads in the local newspaper. Since 2000 the organization has become a major player in judicial races, having purchased $8.3 million in ads for Michigan Supreme Court candidates—$8.3 million, which was not reported under state law.

The rapid rise in unlimited independent spending is even more alarming when the politicians in question are judges, who are supposed to be true to the law, not to campaign contributors. Voters are not surprised when legislators are responsive to their campaign donors, but in a courtroom, ordinary citizens should stand on the same footing as those most powerful in our society. Justice is supposed to be blind, but polls suggest Americans are concerned that campaign cash will influence judges’ rulings.

In his dissent in Citizens United, U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens said the majority’s decision “unleashes the floodgates of corporate and union general treasury spending” in judicial elections. He worried that “States … may no longer have the ability to place modest limits on corporate electioneering even if they believe such limits to be critical to maintaining the integrity of their judicial systems.” Justice Stevens’s warning seemed prescient when the Supreme Court—without a hearing or oral argument—threw out Montana’s law requiring corporations to register as political action committees in order to air political ads.

In Citizens United, a five-justice majority swept aside Justice Stevens’s concerns and held that restrictions on corporate electioneering violate the First Amendment. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that independent expenditures by corporations “do not give rise to corruption or the appearance of corruption.” The Court’s decision rested on the premise that more political speech, even corporate speech, means more information for voters.

In the same vein, Citizens United upheld disclosure requirements in federal campaign finance law. Justice Anthony Kennedy said disclosure “enables the electorate to make informed decisions and give proper weight to different speakers and messages.” Thus Citizens United gutted restrictions on corporate electioneering and left disclosure as the only possible check on corporate political power. Several circuit courts have relied on Citizens United in upholding disclosure rules.

Without effective disclosure laws, the growing tide of unlimited anonymous campaign cash threatens to overwhelm judicial elections. Candidates for state Supreme Courts have shattered fundraising records in recent elections, and more states are seeing special interest money flood judicial elections. The figures for independent spending are hard to discern because the states’ disclosure rules vary widely. It is clear that independent spending has exceeded direct spending by the candidates in many states, meaning that special interest groups—not the candidates—set the tone of the campaigns.

One critic of stricter disclosure laws, Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-KY), claims that such measures are “an effort by the government itself to expose its critics to harassment and intimidation.” The U.S. Chamber of Commerce agrees with this assessment, calling the federal DISCLOSE Act an effort to “upend irretrievably core First Amendment protections of political speech in the months leading up to an election.” The Supreme Court has repeatedly rejected arguments that such concerns render disclosure rules unconstitutional. The Court has said that if a spender can demonstrate that disclosure would lead to intimidation, then applying the rules in that case may be unconstitutional. Thus far, opponents of disclosure have failed to produce any such evidence.

Disclosure is a commonsense reform, and polls suggest the vast majority of citizens—Republican and Democrat alike—support disclosure. These rules are crucial for judicial elections because they determine whether voters can find out who is running ads for judicial candidates. Justice Stevens noted in his Citizens United dissent that a litigant can argue that a judge should recuse herself for receiving campaign contributions from an opposing litigant, but when information on campaign spending is not made public, this right to a trial before an unbiased judge cannot be availed.

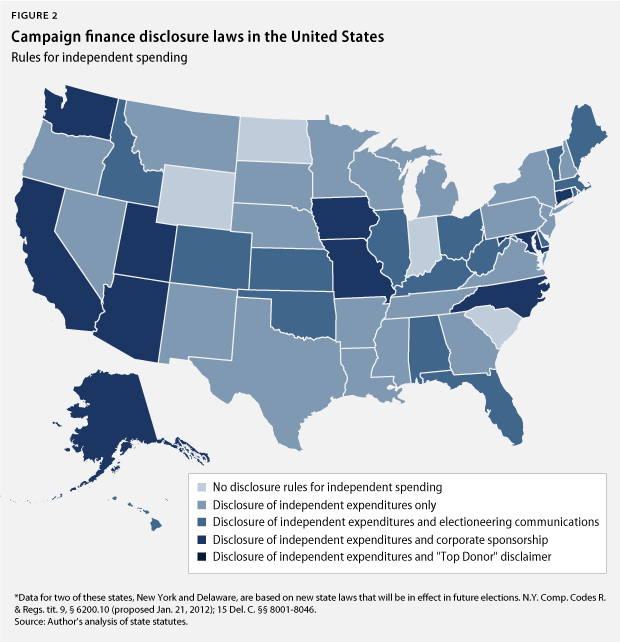

Many states have not yet adapted to the new campaign finance landscape. North Dakota and Indiana, for example, have no rules requiring disclosure of independent spending. Michigan has rules governing independent spending, but they fall well short of full disclosure. Maryland, on the other hand, reacted to Citizens United by enacting rules that require more disclosure from corporations engaged in politics.

Disclosure rules for electioneering communications

Federal law regulates two types of political spending that are independent of candidates’ official spending. Both types mention candidates and are aired before elections. Independent expenditures include ads “expressly advocating the election or defeat of a clearly identified candidate.” Ads that fall short of express advocacy but still “refer to” candidates are considered electioneering communications. Some states such as Vermont use this terminology but subject the two types of independent spending to similar disclosure rules. Most states, including Michigan, fail to regulate electioneering communications at all, even though such ads have been regulated at the federal level since 2002.

Recent elections for the Wisconsin Supreme Court have been overwhelmed by “independent” ads funded by special interests that do not disclose their donors. The sidebar on page 5 discusses how a front group for Americans for Prosperity, a group associated with the Koch brothers, has worked to elect judges who will protect the profits of the Koch brothers and other industrial corporations.

Michigan has no rules governing electioneering communications. In a letter to the state Chamber of Commerce, the Michigan Department of State said it had no authority to regulate “issue” ads that do not constitute “express advocacy.” The agency told the Chamber:

This in no way endorses some of the so-called issue ads, which are often more vicious than regulated ads. Clearly, many if not most of these issue ads are campaign ads without words of express advocacy. Moreover, because they are not considered expenditures, relevant information, such as who paid for them, is often not disclosed.

By avoiding keywords such as “vote for” or “vote against,” independent groups in Michigan can run all the political ads they want without disclosing who paid for them.

The U.S. Supreme Court, in a 1990 case, upheld a Michigan campaign finance law that required corporations to establish a separate account for purchasing political ads. The High Court said Michigan’s ban on spending general corporate funds on political ads was justified by the state’s interest in preventing corruption. The Court said, “Corporate wealth can unfairly influence elections when it is deployed in the form of independent expenditures, just as it can when it assumes the guise of political contributions.” Even though the Michigan Chamber of Commerce was a nonprofit organization, the Court noted that for-profit “corporations therefore could circumvent the Act’s restriction by funneling money through the Chamber’s general treasury.” When it overruled Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce, the Supreme Court in Citizens United opened the door to unlimited independent spending by the state Chamber of Commerce, and Michigan campaign finance law does not require the Chamber to report the source of its money, as long as it avoids the “magic words” that expressly advocate voting for or against someone.

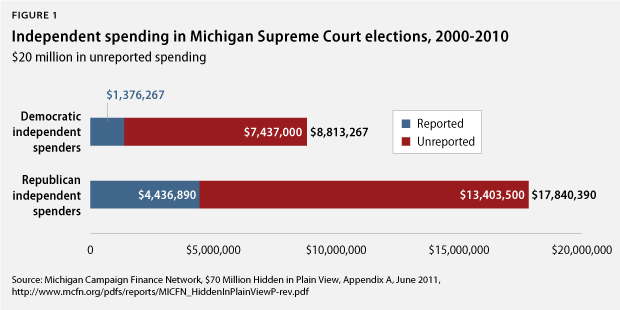

The Michigan Campaign Finance Network has unearthed spending data on electioneering communications for state Supreme Court races. Spending by the candidates themselves has skyrocketed, but the network found that such funds accounted for only 37 percent of total spending on judicial races in the same time period. Of the $27 million in independent spending from 2000–2010, only 22 percent was reported to the state. The Michigan Chamber of Commerce has spent $8.3 million on ads for state Supreme Court races, but all of it has been in the form of electioneering communications, which do not have to be reported. The public is therefore left in the dark, as millions of dollars from special interests influence the Michigan High Court.

Some states regulate electioneering communications but narrow the category so much that it is meaningless. Illinois and Florida, for example, have adopted the definition of electioneering communications that was laid out by the U.S. Supreme Court in FEC v. Wisconsin Right to Life. The High Court limited the definition to include only ads that are “susceptible of no reasonable interpretation other than as an appeal to vote for or against a specific candidate.” In states that use this definition, electioneering communications are defined as ads that fall short of explicitly endorsing a candidate but cannot be interpreted as anything except “an appeal to vote for or against a specific candidate.”

Disclosure rules for donors to independent spenders

The 2009 Wisconsin Supreme Court race saw Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce spend millions on ads attacking Justice Louis Butler. Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce also published a brochure attacking Butler for voting for plaintiffs who sue corporations. Because the ads did not expressly advocate his defeat, Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce did not have to disclose its donors.

Butler lost, giving pro-corporate judges a slim majority. The new court voted 4-3 to reject a widow’s lawsuit against a company whose asbestos-laden products may have killed her husband.

In 2005, Koch Industries purchased Georgia Pacific—the target of more than 340,000 asbestos lawsuits from plaintiffs who developed cancer or lung disease.By purchasing Georgia Pacific, Koch assumed these liabilities, and thus, it had an interest in how the law of asbestos liability developed.

A group affiliated with the Koch brothers’ Americans for Prosperity spent heavily in the bitter 2011 Wisconsin high court election. The group ran “issue” ads which did not trigger Wisconsin’s disclosure rules.

The group’s money helped ensure the court remained in the hands of justices who favor corporations over injured plaintiffs. The Kochs may have spent big to influence the court, but plaintiffs suing the corporation may never know.

Most states that require the reporting of independent spending also require information on those donating money toward such expenditures. Without such information, citizens have to search elsewhere to find the ultimate source of money for independent spending. Most political spenders organized under Section 501(c)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code do not disclose their donors. State laws should require information on the source of funding for independent spending so that citizens know whose money is influencing their elections.

Several states have lower disclosure standards for electioneering communications. West Virginia tightened its disclosure rules after a coal company executive spent $3 million to influence an election to the state Supreme Court, where the company had a $50 million case pending. The state now requires donor information for independent expenditures greater than $250. The threshold for reporting electioneering communications donations, however, is $1,000. North Carolina has the same high standard for electioneering communications but requires disclosure of those donating more than $100 toward independent expenditures. States should not have lower thresholds for electioneering communications because the public probably sees little difference between the two. Both types of ads mention candidates and are aired in the weeks before an election.

Some states require that information on donors be included in the ads. The state of Washington saw its 2006 judicial elections flooded with $2.6 million in independent spending—more money than the state’s judicial candidates had ever spent in a single election. The vast majority of this money came from construction and real estate interest groups. After this explosion in special interest spending, Washington state amended its disclosure rules to require that any independently funded ads list the sponsor and the top five contributors. Alaska, North Carolina, and California also require that such ads include information on the spender’s top donors.

Since much of the money is routed through nonprofit organizations that are not required to disclose their donors, some states impose their own rules on federally registered nonprofits engaged in independent spending on state elections. Connecticut law states that when an organization registered under Sections 501(c) or 527 of the Internal Revenue Code makes an independent expenditure, the ad must list the top five contributors. While North Dakota has no rules governing independent expenditures, it does require any 527 organizations that purchase political ads to report those funders contributing more than $200 each.

As with direct contributions to candidates, many states require disclosure of the employer and occupation of those donating to independent spenders. Other states, including Alabama and Utah, do not require this information. Knowledge of donors’ occupation is important because it allows voters to know which industries favor or oppose the candidates.

Disclosure rules for corporate independent spending

Since the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United, many states have updated their campaign finance laws to impose tougher requirements on corporations. Justice Kennedy’s opinion in Citizens United approved of disclosure rules for corporate political spending:

[P]rompt disclosure of expenditures can provide shareholders and citizens with the information needed to hold corporations and elected officials accountable for their positions and supporters. Shareholders can determine whether their corporation’s political speech advances the corporation’s interest in making profits, and citizens can see whether elected officials are “in the pocket” of so-called moneyed interests.

Maryland law says that an independent spender must do one of two things: First, if the entity issues periodic reports to its shareholders, members, or donors, it can include information on its independent spending in such reports; or second, it can post a link on its homepage to the site where its independent spending reports can be accessed. Campaign finance reform advocates have praised the Maryland legislation. The president of the Maryland Chamber of Commerce, however, criticized these rules as “unnecessary and onerous,” and he alleged that they were “clearly designed to discourage entities from making independent expenditures.”

Connecticut requires detailed disclaimer rules for corporate independent expenditures. Any ads that “promote the success or defeat of any candidate” must include the name of the corporation, its chief executive officer, and its address. Many states—including Arizona, Iowa, and Missouri—require corporations to report that their board of directors approved any political spending.

Corporate political spending must be disclosed to the public so that citizens can know to whom these elected judges will be responsive. Judges will likely hear cases involving corporations active in their states, and, without robust disclosure, a litigant may not know that an opposing corporate party spent huge sums of money to elect the judges hearing the case.

Disclosure rules for last-minute contributions

Any effective disclosure system includes a requirement that independent spenders disclose last-minute expenditures and contributions (i.e., those occurring after the last campaign finance report is filed). With the advent of electronic filing, many states now require reporting—within 24 hours or 48 hours—of contributions and expenditures that occur in the final days before an election. Without prompt last-minute disclosure, citizens will have no idea who is funding independent ads until after the election.

Virginia mandates that all independent expenditures be reported within 24 hours. Utah has a similar rule for electioneering communications. Most states, however, only impose such tight deadlines in the days or weeks preceding an election.

In Pennsylvania, for example, any contribution to or expenditure by an independent spender in the 14 days prior to an election must be disclosed within 24 hours. California requires 24-hour reporting for independent expenditures after October 31 of an election year. South Dakota, Nebraska, and Missouri mandate 48-hour reporting for late independent spending.

States such as Arkansas and Nevada have no rules on reporting late independent spending. In these states, any independent spending in the last week of a campaign will not be reported until after the election. As a consequence, citizens lack information that could prove useful in the voting booth.

Conclusion

States have struggled to keep up with the drastic changes in campaign finance wrought by the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent cases, and the standards for disclosure of independent spending have diverged widely. This year’s judicial elections could see unprecedented independent spending, as the first “super PACs” have been created for judicial races. This makes the need for robust disclosure rules even more imperative.

Some states have sought to shed light on the opaque arrangements between corporations, political organizations, and nonprofits. North Carolina prohibits establishing more than one 527 group with the intent to evade the state’s disclosure rules, but proving the requisite intent might be difficult. Starting in 2013 Delaware will institute a new rule governing donations greater than $100 from corporations or other entities to independent spenders. The independent spenders will have to report anyone who “owns a legal or equitable interest of 50 percent or greater” in the contributing organization.

Policy options: Campaign finance disclosure in judicial elections

- Require reporting of independent expenditures and any other ads that refer to candidates

- Ensure that campaign finance laws require disclosure of the donors who gave money to independent spenders, as well as the donors’ occupation and employer

- Demand that a corporation obtain approval from its board of directors for any political spending and that it report such spending to its shareholders

- Implement rules that require ads funded by corporations and nonprofits to list the top five donors

- Mandate that contributions or expenditures occurring in the final weeks of an election be reported within 24 hours

Because of the unique interests involved in judicial elections, states should consider specific disclosure rules that govern contributions and independent expenditures in these races. Texas limits contributions from law firms to judicial candidates. Further, many states require judges to disclose any campaign donations received by litigants in their courtrooms. States should consider additional disclosure for lawyers and law firms donating to judicial campaigns and for independent spenders running ads supporting or opposing judicial candidates. Disclosure rules could require law firms donating toward independent spending to inform the recipient of all cases pending before the court the candidate hopes to join. The independent spender could then report the information to the state. This would allow litigants to know whether an opposing party has donated money to a judge, allowing them to raise the conflict of interest issue at trial.

As in other elections, independent spending on judicial races is beginning to exceed the money spent by the campaigns. This trend shows no signs of abating. Robust disclosure rules for independent spending have never been more important. The policy options we suggest are intended to illustrate what a strong disclosure system might include, but each state must implement its own campaign finance rules, taking into account a number of factors, including the cost of advertising and political characteristics. (see box)

One thing is true throughout all the states: With the federal regulatory agency paralyzed by partisan infighting, it falls to state agencies to take a tough approach to enforcing campaign finance laws.

Billy Corriher is the Associate Director of Research for Legal Progress at the Center for American Progress.