This issue brief contains a correction.

Millennials are ready for a change in American politics. According to a 2013 poll from the Harvard University Institute of Politics, nearly half—or 48 percent—of Millennials believe politics has become “too partisan.” Generally, Americans believe that their elected officials should work toward compromise instead of advancing a partisan agenda.

If this is the case, why does the American electorate appear to have grown increasingly partisan? According to the Pew Research Center, Americans with less partisan ideologies tend to not speak out: “Many of those in the center remain on the edges of the political playing field, relatively distant and disengaged, while the most ideologically oriented and politically rancorous Americans make their voices heard through greater participation in every stage of the political process.”

Pew’s findings are significant because the Millennial generation associates less with political parties than any other American generation. Approximately half of all Millennials identify as politically independent, and they are the most racially and ethnically diverse generation in American history. Millennials’ relative nonpartisanship, however, does not mean that they are politically apathetic: Young people have made it clear that they are passionate about issues related to state democracies and representative government. They even tend to relocate to states that fall in line with their views on issues such as voter identification laws, representation in state government, and public campaign financing.

Because Millennials care so deeply these issues, they are heavily invested in maintaining a functional, healthy democracy. Redistricting—the process by which an entity draws electoral district boundaries—is essential to ensuring that elected legislators represent the views of a population. This issue brief will discuss the history and effects of redistricting, the different methods that some states use to map their districts, and the benefits and challenges of nonpartisan redistricting for Millennials.

History of redistricting

State legislatures have traditionally been tasked with creating state and congressional redistricting plans. The U.S. Constitution makes no mention of electoral districts, declaring only that “the Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof.” Consequently, each state has developed its own constitutional provisions and laws laying out the process by which it determines districts.

States use the redistricting process to draw the electoral boundaries for both state and congressional representatives. Since the 1960s, redistricting has been conducted every 10 years after the U.S. Census Bureau releases demographic information on national, state, and local populations. The general purpose of redistricting is to review each district and, if necessary, remap districts in order to address changes in population concentration.

Two landmark U.S. Supreme Court cases in the 1960s established that scenarios in which some districts have vastly larger populations than others lead to unconstitutionally unequal representation. In Baker v. Carr, the court determined that decades of failure to redraw districts had led to extreme inequalities in district populations and that it was within the purview of federal courts to provide a remedy. Four years later, in Reynolds v. Sims, the court ruled that this population inequality—also known as malapportionment—violated the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution.

Partisan and predictable districts

Over the past several years, voting experts have tried to find an explanation for the decline in participation among Millennials in the last few elections. Some experts cite a lack of enthusiasm to align with either the Democratic or the Republican Party as a factor. Other experts point to the declining competitiveness of most elections, noting that young people do not feel the need to engage when election predictions heavily favor incumbents. Low Millennial turnout can be addressed by redistricting reform and a new wave of nonpartisan redistricting initiatives.

The competitiveness of elections for the U.S. House of Representatives has been in decline for more than 50 years. Between 1952 and 1980, reelection rates increased 94 percent for incumbents in the House. In 2004, there were 401 House races between incumbents and challengers across the country; challengers defeated the incumbent in only five of those races. Similarly, among the House incumbents who ran for reelection in 2002 and 2004, 99 percent won.

Most states allow politics to intertwine with the redistricting process, which leaves the political landscape predictable—or rigged. This phenomenon is not new to American politics. In 1812, Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry signed a law that allowed for a district shaped like a salamander to benefit his political party, giving rise to the term gerrymandering to refer to the practice of drawing boundaries of electoral districts in such a way that gives one political party an unfair advantage over another.

The 2012 election demonstrated the power of partisan redistricting. Following special elections in 2011 and 2012, Republicans controlled 62 legislative chambers, allowing party members to redraw districts in their own favor. During the 2012 election, Democrats won 1.4 million more votes than Republicans in House races but Republicans won control of the House by a 234 to 201 margin. Some experts have blamed this lopsided result on partisan redistricting and gerrymandering.

Partisan redistricting by North Carolina’s majority Republican legislature before the 2012 elections, for example, resulted in an uneven outcome where Democratic candidates for the U.S. House of Representatives claimed 51 percent of the vote, but only received 4 of 13 seats.* According to a recent Center for American Progress report, “The Health of State Democracies,” North Carolina was ranked 42 out of 51 states and received an F grade for “accessibility of the ballot” and a D- grade for “representation in government.” The report took into account factors such as voting wait time as well as distortion of congressional and state legislative districts.

Methods of redistricting

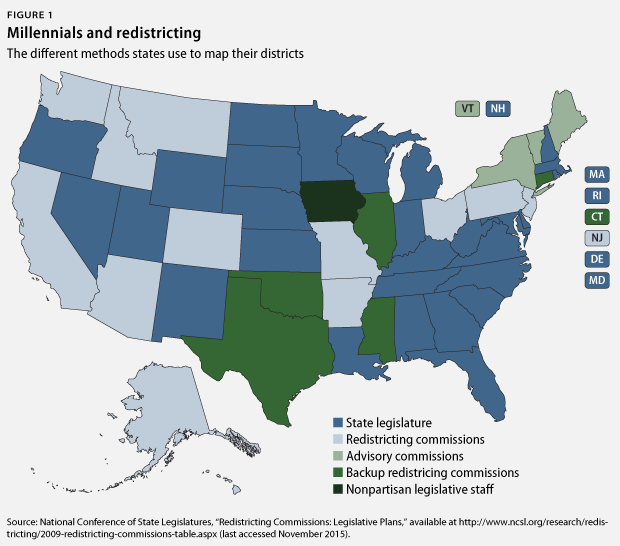

Traditionally, state legislatures have been tasked with redistricting for both state and congressional elections. In order to reduce the role that politics might play in the redistricting process, however, 21 states now employ a commission that is involved, to varying degrees, in the process of drawing district maps for state and/or congressional districts. Some of these commissions are composed of independent commissioners while others consist of elected officials. Of those states that employ a commission, 13 primarily rely on a commission to create plans for state legislative districts: Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Missouri, Montana, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Washington state.

Three state legislatures—Maine, New York, and Vermont—are guided by advisory commissions that do not have primary redistricting responsibilities. Meanwhile, Connecticut, Illinois, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Texas have backup redistricting commissions in case redistricting through the legislative process fails. Iowa conducts redistricting in an atypical manner, placing redistricting responsibilities with a nonpartisan legislative staff instead of the elected state legislature or a selected commission.

Districts drawn by state legislatures

The United States, unlike virtually every other democratic country in the world, leaves redistricting largely to politicians rather than neutral administrative bodies. In some instances, the dominant party will diminish the value of the votes that the opposing party’s supporters cast by packing these supporters into a number of districts that are won overwhelmingly by candidates of the minority party. In other instances, the majority party will fragment the opposition party’s voting base across multiple districts, enabling the majority to win each seat by a relatively small margin.

Some redistricting scenarios reflect what is termed a bipartisan gerrymander or a sweetheart deal in which incumbent legislators maintain the existing balance of political party seats in the state legislature by creating districts that become safe for incumbents of both parties. This scenario is especially likely in states where one party does not control the state house, state senate, and the governorship.

When state legislatures map boundaries that ensure that a particular concentration of voters—such as one party’s established supporters or communities of color—the incumbents who create district boundaries are able to ensure certain outcomes in advance of actual elections. Because those who map the districts will likely be the same individuals who wish to run for office in those districts, there is a serious incentive for incumbents to draw district boundaries in a way that minimizes political competition.

Regardless of whether state legislatures display a partisan gerrymander or a bipartisan gerrymander, these incentives ensure that a majority of districts that are mapped by state legislatures will be redrawn in favor of one political party or the other. According to an article published in the UC Irvine Law Review, “the absence of partisan turnover in more than three-fourths of the districts over the course of an entire redistricting decade has been one of the hallmarks of elections to the U.S. House; and similar, sometimes even more extreme, patterns are found in many state legislatures.”

Districts drawn by state commissions

Over the past several decades, voting rights reformers and advocates have attempted to take redistricting out of the hands of overly politicized legislatures in order to avoid partisan gerrymandering, incumbency protection plans, and “oddly configured districts that fail to respect standard districting principles.” Currently, however, there are no entirely nonpartisan commissions in the United States. All current redistricting commissions at the state level are bipartisan with the exception of Iowa, where redistricting technically operates in a nonpartisan fashion but must still be approved by the legislature. Research has shown that while the commission processes in some states may seem to have partisan compositions, commission states, on average, have lower partisan bias than states where the legislature controls redistricting.

Examples from four of these states—Arizona, Ohio, Vermont, and Mississippi—illustrate the unique ways in which states have designed commissions to reduce the influence of partisanship in drawing district maps.

Arizona

Some state commissions consist of legislative party leaders. A few states have independent commissions where elected federal and state public officials are not permitted to become members themselves but may appoint commissioners who are often political insiders. Arizona is one such state; it tasks a five-person commission with redistricting. Arizona’s process “limits the discretion of legislators by creating a nominee pool; though the legislative leadership chooses four of the five commissioners, they must make their selections from a pool of 25 nominees” chosen by a bipartisan commission using politically neutral criteria. Legislative leadership from both parties chooses two members of the commission. Furthermore, no more than two members can be from the same county. These four appointees then select a nominated independent commission member to serve as chairman of the commission.

In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court reviewed the constitutionality of Arizona’s bipartisan commission in Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission. The Supreme Court ultimately ruled 5-4 in favor of the commission, noting that the elections clause and 2 U.S.C. § 2a(C) permit Arizona’s use of an independent commission to adopt congressional districts.

This was a victory for activists who oppose extreme gerrymandering. According to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who wrote for the majority, “The people of Arizona turned to the initiative to curb the practice of gerrymandering.” Ginsburg also quoted from a 2005 article by legal scholar Mitchell Berman, writing, “Arizona voters sought to restore ‘the core principle of republican government,’ namely, ‘that the voters should choose their representatives, not the other way around.’”

Just one day after this ruling, however, the court agreed to take up another challenge to Arizona’s redistricting system. The court accepted a case brought by a group of Republican voters who assert that the commission’s 2012 state maps violate the “one person, one vote” requirement. They contend that Republican voters were moved around in order to increase minority voter strength in other districts. Furthermore, the plaintiffs assert that the Arizona commission illegally aimed to create districts that are dominated by Latinos in order to enhance these residents’ voting power. This U.S. Supreme Court case, Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, will be decided in the summer of 2016 and will tackle the racial implications of Arizona’s current system.

Ohio

The state legislature sets the congressional district boundaries in Ohio, subject to gubernatorial veto. The state legislative district lines are set by a five-person commission comprised of the governor, the state auditor, the secretary of state, and two commissioners who are chosen by each party’s leaders in the legislature. This process is aided by a separate six-member advisory commission to which the Ohio House and Senate majority leaders each appoint three members. At least one of these appointed members must be from a different party and another must not be a legislator.

On November 3, Ohio voters overwhelmingly approved Issue 1—a ballot initiative that would reform Ohio’s redistricting process. The measure “adds two state lawmakers or legislative appointees to the five member board.” Additionally, it requires that at least two members of the now seven-member board be members of the political party that is not in power. Furthermore, at least two minority party members have to agree on the maps of the state House and Senate districts in order for the maps to take effect for 10 years. If lawmakers do not agree, the maps will have to be redrawn in four years.

Vermont

Vermont has only one congressional district, which makes congressional redistricting unnecessary. Vermont’s state legislature maps, however, are drawn by the state legislature and are subject to gubernatorial veto. Since 1965, a seven-member advisory commission—known as the Vermont Apportionment Board—has assisted in the redistricting process. The governor selects one commissioner from each of the major political parties.

Currently the commission includes Democrats, Republicans, and members of the Vermont Progressive Party. Each of these three parties’ state committee chairs chooses an additional commissioner, which brings the total number of commission members to six. Lastly, the chief justice of the Vermont Supreme Court selects a “special master” to serve as chair of the apportionment board. Because the board serves as an aide to the state legislature, it does not actually determine the maps of the state. Instead, it recommends plans to the legislature, which may adopt, modify, or ignore the recommendations. The legislature can also alter the commission by statute.

Mississippi

Mississippi’s congressional maps are determined by the state legislature and are subject to gubernatorial veto. The legislature draws the state legislative maps as well, but these maps are not subject to veto. If the legislature fails to pass a state legislative plan, however, a five-person backup commission would determine the maps. This backup commission has been in place since 1977 and consists of: the chief justice of the Mississippi Supreme Court; the state attorney general and secretary of state; and the majority leaders of the state House and Senate.

The Iowa option

The Iowa redistricting process is unique. While the legislature does vote on the maps—which are subject to gubernatorial veto—a nonpartisan legislative staff develops the district lines for the Iowa House and Senate, as well as for the U.S. House of Representatives. These nonpartisan staffmembers are assisted by a bipartisan advisory committee, which is composed of five commissioners. The majority and minority leaders of the Iowa state House and Senate are each tasked with choosing a member of the commission in order to create a bipartisan four-person commission. The four selected commissioners then chose a fifth member to complete the commission. The primary task of drawing the maps, however, has traditionally been left to the Legislative Services Agency, or LSA. The legislature considers the LSA’s recommendations substantially and Iowa statutes maintain this. According to LSA Senior Legal Counsel Ed Cook, the staff is comprised of a few individuals—usually three—who are selected each year by the agency director. The individuals who draw Iowa’s maps are selected solely by the agency and not by any elected representatives of any political party.

These individuals “are not allowed to consider previous election results, voter registration, or even the addresses of incumbent members of Congress.” To ensure that the political process is not biased, “No politician—not the governor, the House speaker, or Senate majority leader—is allowed to weigh in or get a sneak preview.” The Iowa mapmakers are forced to abide by nonpartisan metrics that the major political parties agree are fair. Iowa is the only state to utilize this particular process for redistricting.

Iowa has 99 counties that are divided into four congressional districts that are nearly equal in population. Each district includes a mix of urban and rural locations. In order to obtain its goal of protecting residents’ political voices—as opposed to protecting the power of political parties—Iowa has made “population size the primary metric when determining a district’s boundaries, followed by the goal of compact, contiguous districts that respect county lines.” Iowan residents and politicians have noted that more competitive districts encourage individual candidates to represent the people of the district, instead of their political party.

One of the hardest fought congressional elections of 2012 took place in Iowa, and the race provided a useful example of nonpartisan redistricting in action. During that election season, Rep. Tom Latham (R)—who at the time had served 10 terms in the U.S. House of Representatives—learned that his district’s boundaries had changed. In response, Rep. Latham moved 40 miles south from Ames, Iowa, to the Des Moines suburb of Clive, so that he could live in a different district and therefore avoid a primary challenge by fellow Republican incumbent Steve King. Latham was victorious, beating a 16-year Democratic incumbent whose district had also been significantly redrawn. The district is now evenly split among Republicans, Democrats, and Independents.

In other political races across the state, five Iowa lawmakers resigned rather than face election against a fellow lawmaker. Two of them stepped aside for members of the other party. Iowa state senators who are redistricted into districts that have incumbent legislators are required by state statute to run for reelection before the end of their terms. This means that if a state senator is elected to a four-year term in 2010 and redistricting forces this senator into a district along with another incumbent, both state senators would have to run again in 2012 rather than wait until their terms expire in 2014.

The Iowa system, which emphasizes communication and transparency, forces candidates to communicate with voters in a more direct way. The system also receives bipartisan support: In 2011, the new maps were approved by the Iowa House by a vote of 90-7, and by the Iowa Senate, 48-1. After these maps were drawn, Iowa’s four-person congressional delegation was split evenly between Democrats and Republicans.

The implications of nonpartisan redistricting for Millennial voters

It is no secret that competitive elections encourage more individuals to enhance their civic engagement. This trend continues in the millennial generation, where exciting elections have traditionally encouraged a higher voter turnout. Although the concept of using nonpartisan redistricting to create a more balanced and fair democracy through competitive elections has many benefits, it also presents unique challenges.

Benefits

Competitive districts generally appeal to a sense of fairness. In a competitive district, a candidate from either the Democratic or Republican Party has a realistic chance of winning the general election. Competitive districts may also cultivate challengers from a larger group of qualified candidates, including Millennials. Many potential candidates will simply choose not enter into a race in a district where the opposing party generally wins 80 percent of the vote.

Incumbent legislators in districts with an even partisan balance are more likely to pay attention to residents’ needs out of concern that they could lose a close election if voters felt poorly represented. Furthermore, research has found that “evenly balanced districts tend to elect more moderate legislators, because the candidates have to aim for the middle of the political spectrum to increase their chances of getting elected.” Evenly balanced districts could encourage Millennials to turn out in greater numbers, given that they increasingly identify as politically independent.

In addition, candidates in competitive districts will likely campaign with more enthusiasm and spend more of their time contacting voters and mobilizing them to vote. Voters across the country are more excited by competitive elections; this excitement directly correlates with a higher voter turnout.

Challenges

On the other hand, redistricting in a nonpartisan fashion could create barriers to entry that discourage some individuals from running for office. Nonpartisan redistricting creates a higher likelihood that elected officials will have to run competitive elections more frequently. Competitive elections generally cost more, which has the potential to discourage Millennials or low-income candidates from running. This boils down to the fundraising thresholds necessary to be considered a viable candidate.

While involvement in the political process is clearly necessary to address the issues that are most important to Millennials, many Millennials will not throw their hat in the ring due to a plethora of challenges—one of which is the financial burden associated with campaigns. Shauna Shames, a political scientist at Rutgers University-Camden, conducted a study between 2011 and 2014 that surveyed more than 750 young people who were likely to be competitive in a race for elected office. Shames found that the financial cost of campaigning was a tremendous barrier for Millennials who were considering running for public office.

More frequent and competitive elections—such as the scenarios in Iowa that were outlined earlier in the brief—can discourage Millennial candidates from running for office in the first place. Millennials must navigate increasingly overwhelming student loan debt and an unkind economy that forces them to take low-paying jobs; these conditions make it more difficult for young people to invest by purchasing homes or saving for retirement. These widespread financial burdens make the level of fundraising that is necessary to stage competitive and frequent election campaigns unattainable for many Millennials.

More seasoned candidates, by contrast, do not usually have to grapple with these issues. They typically have more contacts, a wider network, and wealthier colleagues to call on for political contributions. While these conditions exist regardless of redistricting method, nonpartisan redistricting efforts could exacerbate them by generating more frequent elections. Though they are not the intended result of nonpartisan redistricting, more frequent elections are certainly an effect to keep in mind as they could disqualify younger and less wealthy political candidates. Shames noted that this challenge could be avoided by decreasing the costs of political elections all together.

Critics of nonpartisan and bipartisan redistricting efforts also point to the composition of redistricting commissions as evidence that the situation is not improving. They argue that most of the state commissions are, ironically, composed of elected officials or individuals who are hand-picked by the very state legislatures that the commissions were created to evade. For example, the current Ohio Apportionment Board consists of: Gov. John Kasich (R), Secretary of State Jon Husted, former Sen. Thomas E. Niehaus (R), Auditor Dave Yost, and state Rep. Armond Budish (D). All are white males older than age 45; they are all Republicans, except for Rep. Budish. The Ohio Appointment Board includes no women, no people of color, and no openly lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender, or LGBT, members.

Even in Arizona, where the commission is selected from a pool of designated nominees, four out of the five commissioners are ultimately selected by the Democratic and Republican party leadership. The fifth independent commissioner is then selected by the four established commissioners. This selection process—although less political than if the state legislature directly created the maps—is still inextricably linked to the politicians who may benefit from gerrymandered districts.

Although the politicians are not drawing the maps themselves, they are selecting the individuals that could draw the maps in their favor. This selection process disenfranchises women, people of color, immigrants, LGBT individuals, Millennials, and voters who are not political insiders. While districting through commissions rather the legislature has generated fairer maps across the country, many of those drawing the maps still belong to the so-called boys’ club. In order to be truly representative of each state’s citizenry, redistricting commissions should work to create space for women, people of color, LGBT individuals, immigrants, Millennials, and voters who are not political insiders.

Redistricting remains a hot button issue at both the national and state level. In 2016, Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission will explore the racial implications of redistricting in a manner that packs minority group into a single district. Individuals in states such as Arizona assert that redistricting commissions divide up voters based on race. They argue that, while commissions take mapping out of the hands of politicians, they do not improve outcomes if they still work to gerrymander districts.

What good are commissions or nonpartisan redistricting if these methods still work to disenfranchise and dilute the power of marginalized communities? Is it enough to take mapping out of the hands of politicians if the individuals replacing them are still conducting business in an unfair manner? These are questions that redistricting brings up—questions to which Millennials want answers.

Conclusion

Nonpartisan redistricting efforts are a valuable step in engaging Millennials in the political process. These efforts aim to realign voting districts in order to make federal, state, and local elections more competitive and fair. Attempts to make the democratic system more equitable work to undo predictable gerrymandering schemes and give every voter an opportunity to affect change. Such attempts have tremendous implications for engaging young people and encouraging them to not only vote, but also to run for office themselves.

In order for nonpartisan redistricting efforts to effectively engage Millennials, however, the selection and composition of commissions should be scrutinized. These commissions should not simply be composed of people with the same motivations as the state legislators. If Millennials are not part of these commissions and do not feel inspired to participate in the democratic system, these systems cannot function effectively.

The 2014 midterm elections indicated that Millennials care deeply about issues. While they have shown that they are uninterested in political party maneuvering, young people are deeply invested in issues that affect their lives, such as raising the minimum wage; common-sense gun violence prevention; student loan debt; and investments in education and jobs programs. Nonpartisan redistricting reforms must develop inclusive criteria that engages Millennials and encourages more women, people of color, immigrants, and LGBT individuals to participate in the political process, in order to better serve young people and make the nation’s democratic system more just.

Sheila E. Isong is the Policy Manager for Generation Progress, where her research focuses on criminal justice reform, gun violence prevention, and voting rights.

* Correction, November 12, 2015: This issue brief has been corrected to clarify the number of U.S. House of Representatives seats that were won by North Carolina Democratic candidates in the 2012 election.