After threats to shut down the government and default on the national debt, Congress instead chose to work with the White House to pass a bipartisan budget agreement that finally delivers some stability for the country. While the budget deal is not perfect, it is a positive step for the economy, and it includes most of the recommendations that the Center for American Progress made in a recent report—“Setting the Right Course in the Next Budget Agreement.”

However, lawmakers still must resolve several lingering issues. First, Congress needs to pass a spending bill to implement this budget deal without ideological policy riders. And when crafting future budget deals, lawmakers will need to include more significant reforms to ensure that the wealthiest Americans pay their fair share. Finally, after this budget deal expires, the White House and Congress will need a plan to remove programs that are not directly related to wars from the war spending budget.

The deal

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 provides $112 billion in new funding to prevent a return to the damaging spending caps known as sequestration for the next two years, with this new funding split evenly between defense and nondefense programs. Before striking this agreement, Congress was writing spending bills for nondefense programs under sequestration caps. These bills would have made sharp cuts in sectors such as infrastructure, education, and the environment. Such spending cuts would have meant disinvesting from programs that grow the economy by supporting low- and middle-income Americans, in addition to hollowing out safeguards that are meant to prevent the playing field from tilting toward the wealthy and special interests. Congress also risked undermining national security by cutting funding for nuclear nonproliferation, foreign assistance, counterterrorism, and other vital security programs that are part of the nondefense budget.

The problems with these sequestration spending bills were not surprising—sequestration was never supposed to happen. Lawmakers agreed to more reasonable spending levels on a bipartisan basis as part of the Budget Control Act of 2011, though even those levels locked in large spending cuts. The legislation included sequestration as a placeholder that was meant to be replaced by a so-called grand bargain on smarter and bipartisan deficit reduction. It was only after this grand bargain failed to materialize that sequestration kicked in. Lawmakers agreed to a smaller budget deal that lifted the spending caps above sequestration levels for fiscal years 2014 and 2015. That deal expired when FY 2016 began on October 1, 2015, with the government operating under a continuing resolution, or CR, to prevent a government shutdown as lawmakers negotiated a new budget deal.

CAP recommended lifting the spending cap on nondefense programs to the bipartisan presequester levels, with an equal increase in defense spending. The new budget agreement falls short of this goal but still provides significant sequester relief and splits the new spending equally between defense and nondefense. The new budget deal increases defense and nondefense spending by $33 billion each in FY 2016 and $23 billion each in FY 2017. The deal reverses approximately 90 percent of the reduction in the nondefense caps caused by sequestration in FY 2016 and approximately 60 percent of the reduction in FY 2017. While this represents significant progress compared with sequestration, far more still needs to be done to rebuild American infrastructure, make world-class education available to all students, and invest in scientific research to drive innovation and grow the economy.

Out of the $112 billion in total sequester relief, $80 billion comes from higher overall caps for defense and nondefense spending. The cost of these increases is offset by a mix of reductions in other spending and increases in revenue collected by the federal government. As has been the case in earlier rounds of deficit reduction, however, anti-tax ideology in Congress sharply limited the policies that could be used to raise revenues.

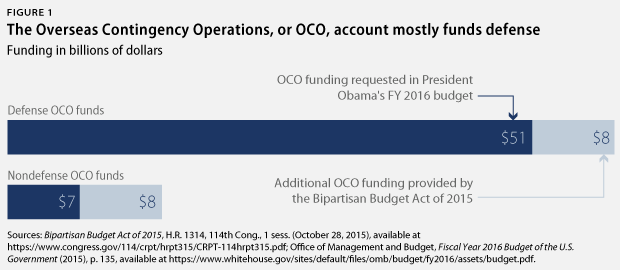

Anticipating this unfortunate anti-tax constraint, CAP encouraged lawmakers to consider lifting the spending caps without offsets if necessary. The budget deal does this by providing an additional $32 billion in sequester relief—also split evenly between defense and nondefense—via the Overseas Contingency Operations, or OCO, account. This fund supports the diplomatic and military costs of wars and is exempt from the spending caps. This is not ideal—it would be better to close wasteful tax loopholes—but at a time when the budget deficit has fallen dramatically while millions of working families continue to struggle, investing in the economy has to be the top priority.

Next steps

While the budget deal establishes a framework for the next two years, it does not actually appropriate any funds to keep the government open after the current CR expires on December 11. Congress still needs to pass an omnibus appropriations bill to allocate funding to specific programs and agencies within the framework of the budget deal. Congress could still provoke a shutdown by insisting that ideological policy provisions, called riders, must be included in the appropriations bill.

In 2013, Congress shut down the government by insisting that any spending bills to keep the government open would have to include policy riders to repeal health care reform. More recently, before passing the current CR, conservatives threatened a government shutdown in an attempt to defund Planned Parenthood. Those two high-profile issues could still provoke a shutdown, but Congress is also pushing to include many other ideological riders that would—among other things—roll back safeguards for consumers, workers, and the environment. Congress will need to pass a clean omnibus appropriations bill to fund the government for the rest of FY 2016, since holding this legislation hostage to demand any of these ideological riders could lead to another government shutdown.

The budget deal also continues a problematic trend in recent deficit reduction efforts by skewing toward more spending cuts and less revenue increases. Since 2010, legislation to reduce the deficit has made about $4 in spending cuts for every $1 in new revenue. The inattention to the revenue side of the budget means that the wealthiest Americans continue to benefit from large and wasteful tax breaks, while spending cuts to education, affordable housing, nutrition assistance, and other programs have fallen hard on struggling families.

The aging of the population means that Social Security and Medicare will eventually require more resources to continue operating in their current form. Fortunately, these programs are not facing an immediate crisis. But lawmakers eventually will need to raise the revenues necessary to sustain Social Security and Medicare—as well as other public investments and safety net programs—for future generations. Policymakers on both sides of the aisle are starting to agree on many provisions to raise tax revenue in a fair and efficient manner, and ideas such as these must be on the table in future budget talks.

Since the lack of revenue limited the ability of lawmakers to negotiate more significant deficit reduction in this budget deal, using the OCO account to provide additional resources to defense and nondefense programs was a good decision. These elevated OCO levels will present a challenge, however, when this agreement expires in FY 2018. While the OCO increases in the budget deal were split evenly between defense and nondefense, the OCO account still overwhelmingly funds defense, with approximately $59 billion for defense and $15 billion for nondefense. Depending on the scale of overseas conflicts in which the United States is engaged in FY 2018, continuing OCO funding at the levels in this budget deal could mean spending far more than necessary on the military.

President Barack Obama’s budget proposal for FY 2016 committed his administration to developing a plan to wind down all OCO spending by FY 2020. The OCO account is supposed to be a temporary response to national security contingencies, not a permanent slush fund for the military. The new budget deal makes it even more important for President Obama and his successor to develop and commit to a credible plan to wind down OCO funding beginning in FY 2018.

Conclusion

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 is not perfect, but in a deeply polarized political climate, this budget deal is a significant step in the right direction. The legislation adheres to the progressive principles that CAP outlined as lawmakers prepared to negotiate and reduces—but does not eliminate—the risk of an unnecessary fiscal crisis. Moving forward, policymakers will need to build on this progress by setting aside ideological riders, paying more attention to the revenue side of the budget, and ensuring that the OCO account does not become a permanent military slush fund.

The recent budget deal proves that lawmakers are capable of doing their jobs by negotiating in good faith instead of threatening to shut down the government or engaging in other forms of political hostage-taking. Hopefully, this trend will continue.

Harry Stein is the Director of Fiscal Policy at the Center for American Progress.