Note: On the first Friday of every month, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics generally releases an employment and jobs report on the health of the U.S. economy. This day usually serves as a moment to reflect upon the recent economic progress of our country as we continue to slowly but surely recover from the Great Recession. But because of the federal government shutdown, this report has been pushed off. Despite not yet knowing how many jobs were created in September, today serves as an opportunity for us to look toward our economic future instead. Over the next months and years as our economy continues to recover from the Great Recession, and monthly jobs reports hopefully show much larger employment gains, who will the workers be that enter the workforce and fill these jobs?

After 43 years as an electric technician, Bob, age 67, is planning to retire later this year and enjoy his days at home with his family.[1] He currently lives with his daughter Violet, but she works long hours and often travels for work. While he enjoys the solitude and the opportunity to be on his own, he also understands that it would be more difficult to do day-to-day tasks around the house without his daughter around, due to his age and dwindling health. Who will take care of him while he is at home alone on most days? It will be people like Marta.

The domestic-worker industry relies heavily on immigrant labor from all over the world. The care workforce, in particular, is crucial to ensuring the productivity of millions of women and men who have to leave their aging parents at home while they go to work. As the home health care workforce and industry continue to grow and the demand for workers in long-term care continues to increase, immigrants such as Marta will play a significant role in this sector, providing direct care for the elderly and for the older population.

Marta is an immigrant who has been working as a caregiver in the United States for 37 years. Her skills as a certified nursing assistant and housekeeper have helped her find jobs in the direct care workforce. She enjoys the personal connection she can provide to her aging clients, working one-on-one in their homes. Like many home health care aides, Marta provides the care, support, and services that the elderly need.

The largest generation of Americans—the Baby Boomer generation—is reaching retirement age, and this demographic wave will create a large number of job vacancies in various industries. But these demographic changes mean that by 2030, there will be more native-born people leaving the workforce than entering it. How, then, will our supply of workers meet the demand for them? In the future, as in the past, our nation will rely on immigrants and their children to fulfill our workforce needs and sustain a growing economy.

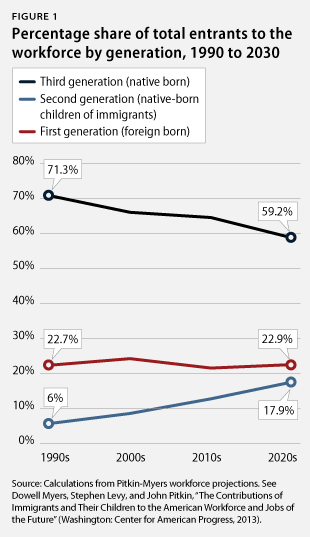

A recent Center for American Progress report by Dowell Myers, Stephen Levy, and John Pitkin indicates that between 2010 and 2030, 58.6 million workers will have left the workforce. The report also projects, however, that only 51.3 million workers who are native born and not of immigrant parents are likely to enter the workforce in this period. Thus, if our country relied solely on native-born people—third generation or higher—it would be 7.3 million people short of the total number of people needed to replace those who are leaving the workforce.

Luckily, however, based on current trends, immigrants and their children—the first generation and the second generation, respectively—will help meet our future workforce needs. In the 2020s, if current immigration trends continue, the number of immigrants entering the workforce will increase by about 12 percent, and the number of children of immigrants joining the workforce will increase by 46 percent.

The growing number of immigrants and their children entering the workforce is important to our economy for two reasons. First, in order to maintain our economy’s current level of production, the number of people entering the workforce needs to keep pace with the number of people leaving it. As explained earlier, without immigrants and their children, our economy would not be able to maintain the present size of our workforce over the next 20 years. Immigrants and their children are therefore responsible for ensuring that, at the very least, our economy can continue to function at its current level of production.

Second, and more importantly, as our nation continues to recover from the Great Recession and as our economy grows, we will need a larger workforce. The need for a larger workforce in the coming years is already evident. The CAP report projects that between 2010 and 2030, there will be about 90 million job openings. Two-thirds of these openings will be due to the mass exodus of Baby Boomers from the workforce, but about one-third, or 30 million jobs, will be the result of job growth. This projected job growth, though, can only be fully realized if there is corresponding workforce growth; the 31.5 million immigrants and their children projected to enter the workforce by 2030 will drive this workforce growth. In fact, 85 percent of the net workforce growth over the next two decades will come from immigrants and their children.

Conclusion

Over the next two decades, the American economy will experience the largest exodus of people from the workforce in our nation’s history. Without immigrants, however, the supply of workers will not match the demand for workers. As such, a sensible immigration system will be vital to our continued growth as a nation. A system that adjusts to the changing needs of the nation’s workforce and successfully admits immigrants into our country for the coming decades will ensure that our economic needs are met.

Angeline Vuong is a Project Manager for the Immigration and Progress 2050 teams at the Center for American Progress.

[1] This is a hypothetical story of an aging Baby Boomer exiting the workforce.