Graduate school is more than just a continuation of undergraduate education. The equity implications of graduate debt, the less generous and less restrictive nature of graduate loan structures, and the forces driving the supply of graduate education highlight the need for new policy solutions.

The equity implications of graduate debt

The continued rise of graduate school debt has significant equity implications that must be addressed. For one, there is evidence that graduate school can undercut the ability of bachelor’s degrees to promote intergenerational mobility. Beginning with Florencia Torche’s 2011 study, evidence shows that there is substantial economic mobility for individuals who only have a bachelor’s degree—meaning that “the chances of achieving economic success are independent of social background among those who attain a BA.”7 However, the pattern does not hold among advanced degree holders, for whom background strongly affects mobility—particularly for men. This suggests that, if left unchecked, graduate school has the potential to hinder all the efforts at boosting mobility that come from undergraduate education.

Fears that graduate school could retrench economic mobility are particularly problematic because women, Black, and Latinx students often need to earn a credential beyond the bachelor’s degree to receive pay akin to less-educated men and white individuals, respectively. On average, women need to earn a master’s degree to exceed the lifetime earnings of men with an associate degree.8 The results are similar when comparing students who are Black or Latinx with white individuals.

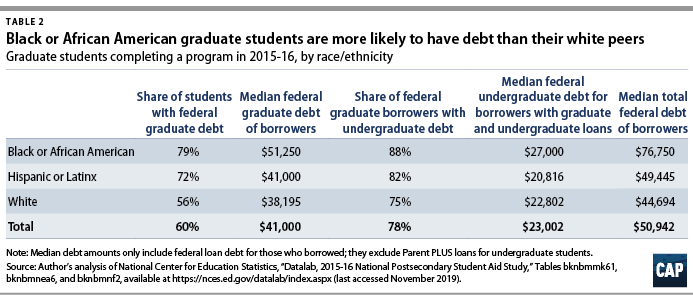

As Table 2 shows, Black and Latinx graduate students are more likely to go into debt than their white peers, and those who finish end up with much more total debt. Almost 90 percent of Black or African American students who took on federal loans for graduate school and finished in the 2015-16 academic year had debt from undergraduate studies. Black students’ median federal debt for graduate school was about 25 percent higher than that of their white peers, and their total federal debt was $25,000 higher. Although Latinx students end up with debt levels closer to those of their white peers, those who borrowed for graduate school and finished in 2015-16 were more likely to have undergraduate debt than their white counterparts—82 percent compared with 75 percent—and end up with about $5,000 more in total debt.

Graduate loans have worse terms than undergraduate loans

Having greater amounts of debt for graduate school also matters because these loans have different terms than undergraduate options. For one, there is essentially no hard dollar cap on graduate school loans. Undergraduate students may borrow no more than $31,000 over their college career if they are a dependent student and no more than $57,500 if they are financially independent adults.9 Graduate students, meanwhile, can borrow $20,500 a year and $138,500 total through one loan program. If they need more than that, they can then tap into the Grad PLUS program, which allows a student to borrow an amount up to the full cost of attendance charged by the college. As a result, nearly one-quarter of graduate borrowers took out more than the lifetime loan limit for dependent undergraduates in just a single year of graduate school.10 That includes just under 70 percent of borrowers seeking a professional degree in areas such as law or medicine.

The interest terms on federal graduate loans are worse than for undergraduate debts. For the 2019-20 academic year, the average interest rate on graduate loans is 1.55 percentage points higher than that on undergraduate loans.11 The interest rate for Grad PLUS loans, meanwhile, is 2.55 percentage points higher than that on undergraduate loans. Graduate loans also do not receive the interest subsidies available for about half of undergraduate loans, which cover any interest that accumulates while a borrower is in school or during their first few years of IDR. To top it all off, Grad PLUS loans also come with an origination fee of more than 4 percent.

Differences between graduate and undergraduate school

The causes behind the rise of graduate debt are also different from those in undergraduate education. In the latter’s case, a big factor driving increases in debt is a decline of state investment that has shifted a larger share of the expense of college onto the backs of students.12 This means that tuition dollars are covering costs that decades ago would have been supported by public subsidies.

About half of graduate students are enrolled in private colleges that by and large do not receive state operating subsidies.

While there has been less discussion about what effect, if any, state cuts have on graduate school pricing, there are several reasons why it is likely less of an issue. One is that about half of graduate students are enrolled in private colleges that by and large do not receive state operating subsidies.13 By contrast, private colleges enroll 22 percent of undergraduate students. Second, the price difference between attending an in-state versus out-of-state graduate program may be less than it is for undergraduate education, at least for the pricier professional programs in areas such as law or business.14

Finally, many graduate schools also appear to be using some graduate degrees as profit centers for the institution.15 Several schools are creating expensive online programs that allow them to enroll more students than they could in person. The Urban Institute’s Kristin Blagg found that the share of students seeking a master’s degree entirely online tripled from 2008 to 2016, from 10 percent to 31 percent.16 By contrast, she found that only 12 percent of bachelor’s degree students are in fully online programs. Many institutions are also turning to private companies to power their online programs, entering into revenue agreements where these corporations take a substantial share of tuition revenue and handle all the recruiting work.17 While the effect of these private providers on the price of the programs has been a subject of much debate, they allow incredibly expensive programs to enroll far more people than they could in a brick-and-mortar setting. And thanks to the uncapped federal loans, schools can offer credentials with prices far out of line with any reasonable earnings expectation, such as a master’s in social work that has median debt of $115,000 and first-year earnings of just $49,400.18

The federal government can no longer be a silent aider and abettor in these graduate debt trends. Few of these graduate programs could keep their doors open without federal loans. And there is nothing in the existing federal system of accountability that ensures graduate programs will be priced fairly and reasonably. The federal government has both the authority and the moral imperative to make sure that educational debt for graduate school does not hobble future generations of Americans.

Solving debt in graduate education requires both broad solutions and those that are targeted to specific fields. Within just one college, graduate programs may include a one-year master’s, a four-year medical degree, and doctoral programs that take nearly a decade to finish. And each may be run by its own unit within the college that handles admissions, pricing, and aid. The debt drivers and solutions thus may range widely across those programs.

Below are a range of potential policies that create indirect or direct incentives to bring down the price of graduate programs, including some that tackle the underlying costs. But graduate education is also an area ripe for innovation. For one, the degrees can vary more widely than the traditional four-year bachelor’s degree or two-year associate degree. The professional nature of graduate education also makes it easier to find better ways to link programs to workforce and employer demands. Overall, this could mean breaking apart long-held views on the length of time required to earn some credentials or requiring more specific proof of the credential’s value in the job market by looking at the earnings of completers.

Judge programs on a debt-to-earnings rate

In 2011, the U.S. Department of Education published the first iteration of its gainful employment rule—a regulation that holds career training programs accountable if loan payments represent too large a share of income for students who received federal aid and finished the program of study. That regulation defined a long-standing statutory requirement that certain programs and types of institutions had to show they provided training leading to gainful employment in a recognized occupation. It then released a new version of the rule in 2014 after a judge invalidated the initial iteration. Gainful employment applies to all nondegree programs, such as certificates, regardless of the type of college that offers them, as well as effectively all degree programs at private, for-profit colleges. If a program fails to stay under the prescribed debt-to-income ratio defined in the gainful employment regulation for multiple years, the program loses access to federal aid.19 Thus, the rule puts pressure on colleges to keep debt balances below a reasonable share of income.

Although the current administration rescinded the gainful employment regulation, the rule had a significant effect on overpriced programs while it existed. Roughly 60 percent of the programs that had debt-to-earnings ratios above acceptable levels shut down even before the rule would have terminated their financial aid.20 It forced colleges to more carefully evaluate their programs in order to rethink price and quality or to eliminate those in fields—such as criminal justice—that might have had student demand but lacked return.21

There have been proposals to expand gainful employment to all other degree programs, both undergraduate and graduate, but there are several reasons why expanding the requirement to graduate programs is more sensible. First, many graduate programs are explicitly professional in nature, so the notion of tying federal support to adequate borrower earnings makes sense. Second, graduate admissions operate much more at the program level—meaning students apply directly to a law school or business school rather than the larger university—and it is harder to transfer between programs. This makes it easier to separate out and evaluate individual graduate programs.

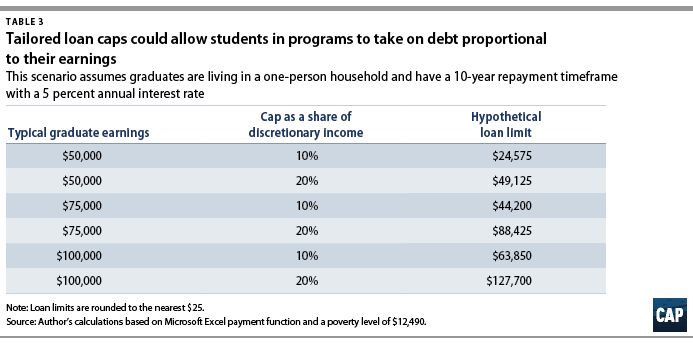

This approach could also be made less punitive by creating consequences that do not go as far as cutting off financial aid. For example, programs could be subject to tailored loan limits set at some portion of discretionary income for the typical graduate who has been in the workforce for a few years. The limit could be based on outcomes for graduates of that program or for everyone who finished a given program type. This approach would be more tolerant of high debt but still address programs that are priced out of line with earnings, such as the more than $100,000 master’s in social work degree at the University of Southern California, which prepares graduates for an occupation with typical earnings of just under $50,000 per year.22 Table 3 provides a few examples of hypothetical loan cap amounts. These amounts do not include any assumptions about undergraduate debt.

Aside from complexity, the biggest downside of a tailored loan limit approach is that it could cause problems at programs that have a societal need but at which the price to obtain the credential is far out of line with the pay involved. This would most likely occur in areas such as teaching or social work, which might have debt caps that are thousands of dollars below program prices. This issue raises an important philosophical question for these types of programs: Whose responsibility is it to make the return on investment calculation work out for careers that generally demand graduate credentials but have lower wages? Should the federal government subsidize the debt so that graduates can manage it through income-driven repayment? Should colleges be required to keep prices down? Or must state and local governments typically employing these individuals raise wages to better reflect the educational demands?

The fact that most graduate borrowers already have undergraduate debt can also complicate the effectiveness of a debt-to-earnings calculation. A program could look like it has an acceptable debt load for students based just on what they owe for graduate school. But the total amount of loans held could be unmanageable. It would be unfair to judge a graduate program on the total indebtedness figure since it cannot control what a student owed from prior credentials and doing so could risk a program turning away lower-income students who had to borrow for their undergraduate education. But the debt-to-earnings approach would at least ensure that the graduate debt alone is manageable.

Enacting a debt-to-earnings requirement for graduate programs must be done separate from efforts to restore the gainful employment regulation.

To be clear, enacting a debt-to-earnings requirement for graduate programs must be done separate from efforts to restore the gainful employment regulation. While there are worries for both graduate programs and career training options, the problems with the latter are more concerning. Traditionally, calls for applying gainful employment requirements for all programs are a delaying tactic that avoids accountability for any program types. This recommendation rejects the idea that accountability for career training programs should wait until a debt-to-earnings measure is applied more broadly to graduate programs.

Hold programs accountable for loan repayment and IDR usage

Rather than capping debt based on the earnings of completers, graduate programs could instead be held accountable if many students are unable to repay their debts or are heavily reliant on options such as IDR, which sets payments at a share of income. This has the advantage of allowing higher-debt programs to continue operating as long as their outcomes justify the investment. Unlike current policies that apply to undergraduate loans, the focus is on repayment instead of default because projected default rates are already very low for graduate borrowers, likely due to the fact that having a bachelor’s degree increases their earning potential and therefore their ability to pay down debt.23

There are good policy reasons for being worried about the excessive usage of IDR. For students, the issue comes down to interest accumulation and the possibility of paying more overall on their loans. While IDR plans have different rules for forgiving some interest, many borrowers can and likely will see their balances grow if their payments are too low. That can result in them potentially paying much more over the life of the loan or owing a significant tax bill 20 years down the line when their remaining balances are forgiven.24 Taxpayers, meanwhile, pick up the other end of the costs that borrowers don’t bear. That means covering interest that is forgiven during repayment, as well as any amounts forgiven after 20 or more years in repayment. While the notion of some government costs for IDR is reasonable, a system that results in borrowers paying a lot more for longer and taxpayers picking up the forgiveness tab while the program avoids any consequences for generating debt that could not be repaid is not fair.

The challenge with judging programs on IDR usage is that it creates a tension between the use of a federal benefit for students and potential consequences for graduate programs. An overindebted borrower who needs payment relief absolutely should pursue IDR if it will help them avoid default and the ruinous consequences associated with it. But some students might be able to pay a higher share of their earnings yet prefer the payment relief, which a school cannot control. That means judging programs on IDR usage could result in them encouraging some borrowers to not use a federal benefit that is available to them. Signing up for IDR is also outside programs’ direct control, so they could label this as an unfair form of accountability. Finally, students could end up using IDR not because their graduate debt balance alone is too high but because they cannot afford payments on those loans combined with what they already owe for their undergraduate education. Looking at IDR usage thus risks discouraging programs from enrolling students who had to borrow for their bachelor’s degree.

Given these challenges, attempts to judge programs on IDR usage or repayment rates should pursue one of two avenues. One approach is to set the threshold for acceptable IDR usage very high—such as a at large majority of borrowers. This means the government will only worry about IDR usage when it becomes the overwhelmingly common repayment option for students. This still has some concerns about discouraging borrowers, but programs above the cap would have a harder time arguing that the overreliance on IDR is not a function of too much debt.

Alternatively, policymakers could enact a repayment rate regime alongside changes to interest accumulation on IDR. For example, forgiving all interest for the first three years on IDR and then judging programs on the share of balances paid down after five years would give borrowers time to land on their feet and ensure that negative amortization is not just a result of students going on IDR while they find a job in their first few months after leaving school.

The consequences attached to a repayment rate or an IDR usage metric also matter. These indicators are less well-suited to severe penalties such as making programs ineligible for federal loans because of worries that some repayment decisions are outside programs’ control. Instead, a system of either capping debt or requiring risk-sharing payments is a better consequence for programs that are too reliant on IDR or for which borrowers cannot repay.

Create dollar-based caps for graduate loans

If an outcomes-based approach to limit debt is too complex, the federal government could instead create new annual and aggregate limits that cap how much money a student can borrow for graduate school.25 This moves away from the current regime, where institutions determine limits by setting their cost of attendance. At the very least, these limits would have to vary by credential type and length since there are significant differences in anticipated debt levels for a one-year master’s degree versus a multiyear doctorate. Even then there may still need to be variation for specific types of programs. For example, medical and dental degrees cost a lot more to operate and thus charge much higher tuition than most other types of doctorates.

Dollar caps on loans also have the benefit of avoiding concerns about how the interaction between graduate and undergraduate debt could affect borrower choices around the use of IDR or potentially understate the full amount owed on a debt-to-earnings calculation.

There are, however, significant risks associated with stricter loan caps. Lower federal limits could create a larger market for private loans with poor terms and fewer repayment protections. Such a substitution is arguably worse than simply keeping the existing loan structures. One way to address this would be to prohibit schools from certifying any private loans above the federal cap and to remove any repayment protections that those types of debts currently receive—such as being almost impossible to discharge in bankruptcy. This would not fully address direct-to-consumer private loans but might make it a little harder to generate more nonfederal debt.

While this report does not consider how dollar-based caps could be determined, any process to set them must ensure that limits do not get constructed in ways that create equity concerns. This problem could arise by setting caps that are lower for programs such as master’s programs in education or social work that are more likely to enroll borrowers who are women, Black, or Latinx.26 This again raises the question about the best way to address broader societal mismatches between credentials needed for certain professions and pay for those jobs. While debt limits cannot solve the pay side of the equation, any loan cap should at least come with an equity analysis to ensure it does not create disparate effects.

Any cap on graduate debt would have to come as part of a deal that did not require reducing spending elsewhere to make this change.

Finally, this policy suffers from a major budgetary downside. Graduate loans, especially Grad PLUS loans, currently score as making large sums of money for the federal government. As a result, any plan to cap these debts would change the expected revenue they bring in and thus cost money. Given the need to fund many other federal higher education programs, any cap on graduate debt would have to come as part of a deal that did not require reducing spending elsewhere to make this change.

Ban balance billing

It is common in higher education for students and families to face direct academic charges well in excess of what federal financial aid and an expected family contribution provide. This is often referred to as “gapping” students.27 This bears some similarities to the concept of “balance billing” in health care: charging patients an amount of money in excess of what their insurance company will pay for a service.28

The federal government already bans balance billing in some health care contexts such as the Medicare Advantage program. Medicare Advantage offers insurance plans from private providers that an individual can select instead of typical Medicare coverage. To keep the costs of these plans down, Medicare Advantage plans set expectations for patient cost sharing, ban all balance billing for participating providers, and cap charges at 115 percent of the Medicare rate for nonparticipating providers.29 That means that the provider of health care services cannot charge a patient an amount too far in excess of what Medicare would pay for that service.

A similar approach in higher education would set maximum amounts that the federal government was willing to pay, expressed in terms of how much in federal loans it would provide. Student and family cost sharing could be determined through a needs analysis that determines a reasonable amount, with caps that limit how far above those amounts a school could go. This needs analysis would need to be different from the existing system, which typically produces unrealistic expectations for students and families and generates an expected family contribution that is not actually an expression of what they are likely to pay.30 It would be reasonable for the allowable loan debt to go somewhat above the contribution amount to acknowledge that some borrowing for graduate school is acceptable.

Banning balance billing has some similarities to ideas for tackling undergraduate affordability, such as CAP’s Beyond Tuition proposal. Both ideas involve setting clear limits on what families or students can pay out of pocket. The big difference is that Beyond Tuition presumes significant increases in federal spending on college to make it so that families can attend school where they would only use debt if they could not afford their expected contribution. Banning balance billing in graduate school, however, does not assume new federal money for affordability. And it would presume some borrowing as part of the family contribution, just not as much debt as students take on today.

Living expenses represent a challenge to the balance billing concept. Apart from dorms, dining halls, bus lines, or other services run by colleges, it is hard to hold institutions accountable for the cost of living near campus. Some students may also already have families or dependents that have child care costs or other things that are not directly in the school’s control. As a result, any kind of balance billing prohibition would need to consider how to allocate the federal aid and family contribution so that it does not get entirely swallowed up by the college, leaving nothing left over for rent or food. Given these challenges, any approach that makes bills more predictable and reasonable—such as standardizing room and board calculations or setting amounts by geographic region—would be a step forward.

A bundled payment model is another way to simultaneously address academic and living expense costs. Bundled payment is a health care concept in which the insurer pays a set amount for all elements of a specific health event. For example, a bundled payment for hip replacement could cover the surgeon, anesthesiologist, hospitalization, and follow-up rehabilitation instead of separate charges for each.31 In higher education, the federal government could create a bundled payment that combines the academic and living expense elements of the price. This bundled payment approach could thus separate out within the allocation what the school can receive versus what can go to other expenses.

Institute price caps

Many of the solutions outlined above address a core issue—that the price for a program is too high—but they do so indirectly. It is also worth considering the most direct approach: instituting price caps. Doing so would put pressure on programs to reduce their costs or find new ways to subsidize the price. At the same time, instituting price caps has significant potential for creating supply shortages or reductions in quality, which must be addressed.

Having the federal government explicitly dictate the price of higher education is a third rail, but it is not unheard of in other policy areas.

Having the federal government explicitly dictate the price of higher education is a third rail, but it is not unheard of in other policy areas. For example, Medicare has set payment rates for given procedures, which can be adjusted based on other factors.32 This allows the government to use the fact that it is a major purchaser of health care services to negotiate more advantageous prices.

Politics aside, there are two computational challenges with a federal price control regime for colleges. One is that in many cases, an institution’s listed price is not what is charged thanks to grants, scholarships, and tuition discounts. Thus, a price cap could still allow out-of-pocket spending to rise if subsidies decline. For example, if a school lists its price of attendance as $40,000 per year but gives everyone a $20,000 grant, students pay $20,000. If, thanks to a price cap, the school lowers its price to $25,000 but then eliminates the grants, students end up paying more out of pocket than they did before. Accordingly, any attempt to rein in prices would have to look at the net price—the amount that a family pays out of pocket. The one downside to this approach is that it could create some timing challenges because average net price will not be known until everyone has received their aid packages for the year.

The second issue is that the price of college is really two different items: direct academic expenses for costs such as tuition, fees, books, and supplies; and living costs such as food, housing, and transportation. The former is more squarely under the control of institutions—although sometimes state legislatures set tuition rates for public colleges—but the latter is not, unless a school operates dormitories and cafeterias. Holding an institution accountable for capping the price of off-campus living is not feasible. Given these challenges, this section considers a narrower idea of a price cap.

Unless explicitly noted, all other references to the word “price” in this section refer to the net price for direct academic prices or living costs that the institution controls. It also excludes elements of living costs that an institution might control, such as dorms, because all students might not use them. The limited focus on academic expenses does create some challenges for effectiveness: If a school keeps its price of attendance down but the price of housing in the area spikes, a student will still face affordability challenges that are not the institution’s fault.

A federal price control for higher education could be applied in varying levels of aggressiveness. One would be akin to rent control: a cap on the rate of price growth. Instead of dictating the overall price, the government would require that any federally funded program not increase its price more than a set amount each year. That level could be set at a fixed dollar amount or the change in the Consumer Price Index. Doing so would acknowledge that cheaper programs may see larger percentage changes that represent smaller dollar increases.

Alternatively, the federal government could establish reference prices for different programs. This is an idea borrowed from the health care space where the purchaser of health care services on behalf of enrollees will set a maximum price they are willing to pay for a given nonemergency procedure such as a hip replacement.33 These purchasers will then encourage patients to choose lower-cost providers, creating an incentive for those over the limit to bring their prices down as well. Patients can still select a provider over the reference price if they wish, but they do so with a clear message that they will need to cover the amounts over that cap.

A reference price in higher education would need some modifications from the health care context. In this scenario, the government would set a maximum dollar amount of loans it would provide for different types of programs. But it would need additional protections so that institutions cannot just cover amounts over the reference price through private or institutional loans. To address that concern, the federal government could either prohibit the institution from certifying any institutional or private loan for amounts over the reference price, or it could remove lender protections for debt amounts above the cap, such as prohibiting forced collections of those loans and making them dischargeable in bankruptcy with no waiting period. This approach thus allows for out-of-pocket spending and some reasonable levels of debt, but not other ways to make students pay more in the future.

Regardless of the option chosen, any price cap program will face several challenges beyond the issues of politics and optics. One is what to do about institutions or programs that simply cannot afford to operate under these caps. It’s highly likely that these might be lower-resourced colleges, some of which could serve larger numbers of students of color.34 That creates some risk that these programs might close, denying access and raising concerns about equity. This could be even more problematic if the program has good outcomes despite its higher price. Another risk is that an institution may respond to a price cap by redirecting subsidies from undergraduate to graduate education, which may not be the best use of money.

A price cap also runs the risk of creating supply shortages or a degradation in quality. If colleges heavily subsidize spots to meet the price cap, then they might have to shrink enrollment significantly. This could be a good thing if colleges are charging too much or creating an oversupply of graduates. But it would be bad if a constrained supply results in fewer spots than are necessary or in a system of rationing that results in places disproportionately going to wealthy or white students. Alternatively, a college could avoid rationing but simply lower the quality of a program to lower its operating cost. A cheap program that is of low quality could arguably be worse than a program that is at least a little too expensive. All of this means that any price cap would require a lot of upfront work to think through possible institutional responses and how to handle them.

Tackle specific credentials

The above policy ideas focus on broad solutions that could be applied across any range of credentials and program areas. But if none of those ideas work, then it may be worth pursuing options that target specific credentials. Doing so could eliminate hot spots of concern. In some cases, these credential-based solutions could also help rectify issues that make other ideas such as loan or price caps unworkable because of fears about societal demand for degrees being mismatched with pay for jobs such as teachers or social workers.

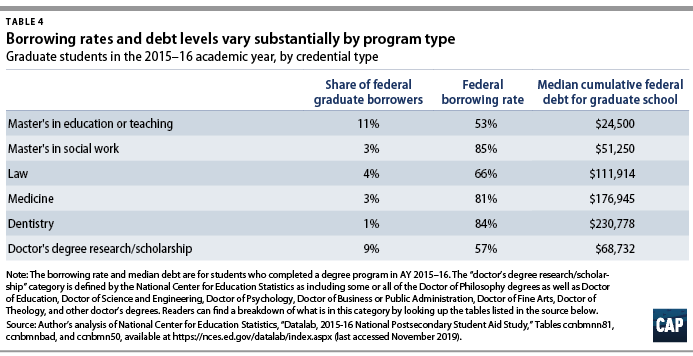

Given these considerations, this section contains recommendations for six types of credentials that are common across graduate school. Two—teaching and social work—are for fields where credentials are often required by law or expected by employers but which have lower returns than many other careers that demand graduate degrees. Three others—law, medicine, and dentistry—are for fields which are the most common examples of high debt but which generally lead to high salaries. These five credentials represent about 22 percent of graduate borrowers with federal student loans. The final is doctoral degrees for research and scholarship, which represent about 9 percent of all federal graduate borrowers. This is a category created by the National Center for Education Statistics that includes almost all doctorate of philosophy, doctorate of education, and doctorate of science or engineering degrees, as well as 60 percent of doctorate of psychology degrees and 75 percent of doctorate of business or public administration degrees.35 It is contrasted with professionally oriented credentials in law, medicine, theology, dentistry, chiropractic, and pharmacy, among others. Although doctoral students in research and scholarship areas often receive some funding from their institution, they also can take a long time to complete and often lead to modest-paying careers in fields such as the liberal arts, meaning that they have the potential to generate unaffordable debt. Table 4 provides more information on the borrowing rate and debt levels of students in these programs.

The general idea behind the following recommendations is to move away from a system that tries to make these credentials affordable through back-end repayment options and loan forgiveness to a system with reasonable operating costs and prices charged upfront. Providing benefits upfront would help aspiring graduate students understand exactly what they are getting into. Dealing with issues of price and the number of slots in some programs could also be a way to improve equity in programs that fail to enroll large numbers of low-income students or students of color by making prices seem less formidable and engaging in intentional recruitment strategies. An upfront approach would also make it easier to attract people to serve in roles where there are national shortages—such as rural doctors or lawyers—by setting aside spots for individuals who will commit to this kind of service.

Admittedly, these ideas will not solve every issue with graduate schools. They do not touch terminal master’s degrees—such as a master’s in business administration—that appear to be a source of profit for schools with undetermined value for students. But they are a starting point to address some of the highest-debt fields.

Teacher and social work master’s degrees: Required affordable options

About 14 percent of graduate borrowers are pursuing a master’s of education, teaching, or social work. In both education and social work, it is not uncommon for employment or pay raises to require a master’s degree. Yet in both cases, the compensation that the professional receives in return may not be enough to easily pay down their debt. This report does not weigh in on whether such degrees should be required except to note that there is a need for multiple pathways into the teaching profession. But in cases where these credentials are either a necessity or provide a guaranteed income boost, there should be requirements for the provision of affordable, high-quality options that do not cannibalize the full economic boost that the borrower receives.

Regarding teacher training, states must step up to the plate and ensure that programs at public colleges are both of high quality and affordable. The former should entail ensuring that teacher credentials impart the skills and knowledge that make teachers more effective in the classroom. This can include extended clinical practice, particularly for alternative certification master’s degrees, and increased emphasis on coaching or mentoring, content, and pedagogical knowledge.

Once states have ensured that teachers’ credentials are of high quality, they must also work to make them affordable.

Once states have ensured that teachers’ credentials are of high quality, they must also work to make them affordable. In cases where a master’s degree is required for certification or licensure by states or districts, the state would have to commit to providing high-quality, in-person options for all teachers or social workers that can be repaid by a reasonable share of their salary over a defined period of time, ideally one shorter than the 10 years it takes borrowers to receive Public Service Loan Forgiveness. States could choose whether to provide these options at public or private colleges and how many offerings they would need given the geographic dispersal of students. States should still aim for affordable repayment goals if the credential is not required for employment but tied to a guaranteed pay raise. In that case, however, it would be reasonable for borrowers to either pay more or for longer since the credential is somewhat voluntary.

Ideally, states would address this challenge by lowering the price of their degrees upfront because that would create the least amount of additional implementation work on the backend and ensure that students will not be scared away by higher prices. This would also avoid confusion about how post-school assistance might interact with federal IDR plans. If states want to ensure that degrees are affordable through forgiveness plans or repayment benefits, they must make sure that they do not add lots of complicated eligibility criteria or take other steps that could save money by making most students unable to get relief.

Medical and dental school: Greatly expand the National Health Service Corps

Roughly 4 percent of graduate borrowers are pursuing a degree in medicine or dentistry. But these programs are also extremely important for filling national needs, and these degrees typically have the largest debt balances in higher education.

There are a few key issues worth tackling around medical education and the associated profession. One is that these programs must do more to enroll a diverse student population.36 Another is that doctors are too often drawn to high-paying specialties, resulting in shortages of primary care physicians, especially in rural areas.37 There is an estimated need for more than 13,000 more primary care physicians, and the Association of American Medical Colleges speculates that the need could triple by the 2030s.38 Even if medical schools grow or become more diverse, projected shortages of residency spots may also become a challenge in addressing doctor supply.

While reforming medical education financing alone may not be enough to solve these challenges, some changes may help. One would be to greatly expand programs that provide upfront subsidized medical school training. For example, Congress could greatly expand the scholarship component of the National Health Services Corps (NHSC). This is a program run by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that covers up to four years of academic expenses plus a support stipend at medical school or dental school in exchange for service in an area with a shortage of health service professionals—including rural and urban areas.39 Students must serve at least two years for the first year of scholarship money received, with the requirement increasing by one year for each additional year of funding. The overall service requirement is capped at four years.

Greater funding could close the gap in the number of students served by the NHSC scholarship compared with its various loan repayment options. These repayment options include programs that repay up to $50,000 of loans per year for the first two years of a service requirement plus additional amounts after, and another of up to $120,000 for students in their last year of medical school.40 There are about 200 scholarship awards each year compared with roughly 5,000 loan repayment agreements,41 and only about 10 percent of applicants receive scholarships.42

Expanding the NHSC would also entail addressing how it is funded. The NHSC is currently funded through the discretionary appropriations process. That means Congress must choose to spend money on the program each year, and funding for it must compete with all other priorities in the bill that funds labor, health, and education programs—a system that makes it hard to secure sustained increases.

One downside to expanding the NHSC scholarship is that it has punitive terms for participants who do not fulfill their service requirement. They must pay back an amount equal to three times what the government paid on their behalf, minus some adjustments for portions of the service requirement they met.43 This raises some potential worries because other federal grants that convert into loans if requirements are not met can end up being a nightmare for participants to sort through.44

Expanding the NHSC should also come with greater emphasis on funding spots for students who may not traditionally have as common a presence in medical schools. This could mean placing a greater emphasis on the existing priority for individuals from “disadvantaged backgrounds” in awarding funds.45

Having the federal government more directly fund spots in medical schools would match the fact that it is already the main funder of post-school residencies. The Direct Graduate Medical Education program funds residency spots and their salaries by distributing dollars to hospitals.46 The largest of these funds come from Medicare and amounted to more than $10 billion in fiscal year 2015, but there are also funds from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the U.S. Department of Defense.47 Addressing medical school spots thus could help the federal government address policy issues related to promoting equity among the residency spots that it is already funding.

A funding approach focused on subsidizing medical or dental school spots also creates a way to reward institutions that do well in promoting equity. It could increase capacity or improve affordability at places that do particularly well at creating diverse medical or dental school classes with graduates who succeed when practicing.48 The federal government could also leverage its existing funding for residencies by making hospital payments based on performance, such as whether residents practice primary care in rural areas.49

Law school: Move to 2-year programs and better integrate with undergraduate education

About 4 percent of graduate borrowers are in law school, although law students, like medical students, can have very high loan balances. There are two ways to bring down the cost of law school. The first would be to shift from a three-year program to a two-year degree or make the third year an externship that carries minimal tuition charges. This approach would have to be different from existing accelerated law programs, which simply try to fit three years of curriculum into a two or two-and-a-half-year period. Instead, this approach would mean shrinking the number of credits required to graduate.

The idea of a two-year law degree has gained currency since a 2013 New York Times op-ed advocated for it, and as that piece noted, the concept has been discussed since the 1970s.50 While the idea has not yet taken off, law school enrollment has been on the decline for years, and law schools are losing as much as $1.5 billion a year, according to estimates.51 That means law schools may struggle to maintain the status quo and could need significant changes.

Federal involvement in shrinking law school lengths could admittedly be an even bigger step than price caps. The length of programs is well-understood to be an element of academic discretion in which the federal government does not get involved. Federal law does require institutions to “demonstrate a reasonable relationship between the length of the program and entry level requirements for the recognized occupation for which the program prepares the student.”52 But this would assuredly allow three-year degrees at law schools. Therefore, any attempt to shorten law school programs would either require a change in federal involvement in program length or adjustments by state licensing bodies and the American Bar Association (ABA) to their own standards.

The second approach to easing the cost of legal education is even more radical: creating a pathway to a certified credential in bachelor’s degree programs. While such an approach may not be suitable for all legal specialties, it would make sense to create paths to practice some type of law through an undergraduate degree—for example, a certification to handle wills or simple contracts—an approach some states are already considering.53 This could make it easier to fill legal needs, especially in rural areas, many of which are facing significant lawyer shortages.54

This solution also runs into a challenge with what is allowed by existing state regulators or by the ABA. It would require action on their end, and there may not be a clear federal mechanism for requiring this change to happen. While that can be a barrier to change, it could allow states or the ABA to set up some demonstration programs to test the idea. Here, the federal government could potentially help. It could consider temporarily waiving accountability requirements—including some of the new ones described above—for programs that decide to test out shorter lengths or integration with bachelor’s degrees.

Research-based doctoral degrees: A mandatory matching program

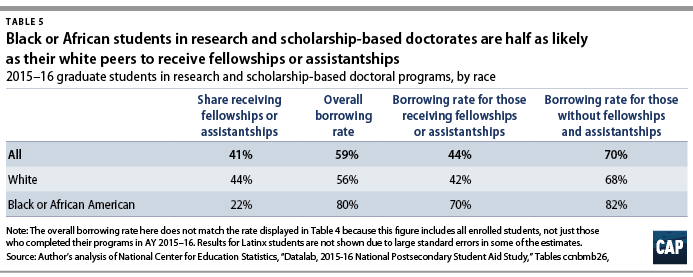

About 9 percent of graduate borrowers are in doctoral degrees focused on research or scholarship, meaning that they must complete a dissertation and are not in an area that leads to professional practice, such as medicine, dentistry, podiatry, or law.55 This includes doctorates in fields such as engineering that prepare graduates for high-wage occupations as well as disciplines in the liberal arts that lead to much lower earnings. About 40 percent of these students receive a fellowship or assistantship, although white students are twice as likely as Black students to receive this kind of help. (see Table 5) As a result, while about 60 percent of students in research-based doctoral degrees borrow, 80 percent of Black students in these programs take on loans. Unfortunately, data on Latinx students are not available due to large standard errors in the estimates produced.

Taking on debt for research-based doctorates is a potential concern. For one, these programs are quite long, meaning that even if they borrow relatively low amounts, students could accumulate a lot of debt over time, as well as large accrued interest balances. The result is that doctoral students with higher debt, especially if they are not entering high-wage occupations, may have a hard time making payments without using IDR.

The federal government can address these concerns by requiring programs to fund students pursuing doctoral degrees in research or scholarship fields for at least four years and then cap debt for the remainder of the program. The idea is that colleges would only be able to offer doctorates in these fields for funded students and that such funding must be sustained for most of the program. Such funding could include stipends for teaching classes. Beyond the initial funding period, the institution would then be required to match funding based on how much a student must borrow. There would also be an overall cap on each student’s debt around the starting salary for a tenure-track professor in that field—a version of the idea above about tailored loan limits, except that these are based on anticipated jobs as opposed to the actual earnings of graduates. This provision would both ensure that debt is more reasonable and that institutions have a strong incentive to ensure that students finish their degrees in a timely fashion.

Requiring funding for doctoral students has some complications. For example, institutions could raise prices to cover funding for scholarships. Institutions could also cut back on the number of doctoral spots offered. Depending on the field, this is not inherently bad. There are significant worries about an oversupply of doctorates compared with the number of available jobs.56 If universities had to do more to cover the cost of producing those graduates, they might be inclined to right-size the number produced. That said, the biggest risk and concern with any reduction of supply is whether the remaining spots disproportionately go to students who are wealthier or white. Another problem with this category of credential is that it is not as clear cut as the others discussed above. For example, the National Center for Education Statistics category used to identify these types of programs includes some but not all doctorate of psychology degrees. Attempts to create clear policies for these types of credentials would need to start with a more structured definition of what should be covered. Finally, policymakers would need to decide how to handle living expenses when determining loan caps or matching requirements.