Over the next six weeks, Washington, D.C.—and especially the U.S. Congress—is going to be completely obsessed with the federal budget. But over the past week, there have been a handful of important releases of new economic data that show just how off-track that discussion really is. The new data underline the struggles of the middle class and the continuing drag of poverty and inequality. They also reveal that government debt, while once on a legitimately concerning trajectory, is now on a much more manageable path. Taken together, the numbers should make policymakers turn away from yet another damaging and acrimonious debate over deficits and toward a conversation on the pressing problems facing the country right now.

The Census Bureau released its annual report on income, poverty, and health insurance coverage yesterday, and the findings are alarming. Fully 15 percent of Americans, or 46.5 million people, currently live in poverty—an elevated level that has remained essentially unchanged since 2010 even though our economy is supposed to be in recovery. A broader measure of hardship that more accurately captures the difficulty American workers are facing—the share of Americans with incomes below twice the poverty line—now stands at 34.2 percent. This number has not fallen in two years and represents a 12.1 percent increase over prerecession levels.

But low-income families aren’t the only ones getting left behind in this economy. The middle class has actually seen its income drop since the end of the recession, even as those at the top have more than fully recovered. The Census data indicate that the top 5 percent of Americans have increased their real incomes by 5 percent over the course of the recovery, while the middle 60 percent have lost 1.2 percent of their income.

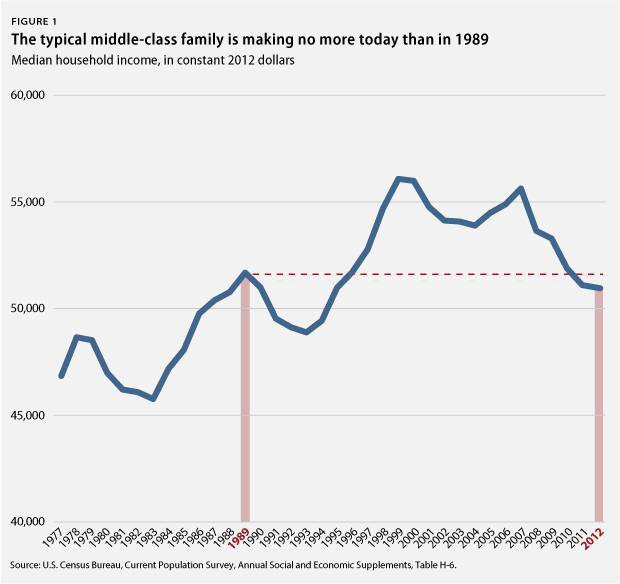

Consider what has happened to median family income. For a household right in the middle of the income distribution, the events of the past five years have not only stripped away all of the gains made after the 2001–2003 recession, but they have also undone all of the income gains of the 1990s boom. After adjusting for inflation, the typical middle-class American family is now earning less than they were earning in 1989. In other words, the middle class has lost nearly a quarter century of economic progress.

At the same time, the richest of the rich seem to be operating in an entirely different reality from the rest of us. New data from economists Thomas Picketty and Emmanuel Saez show that fully 95 percent of the nation’s income gains over the first three years of the recovery flowed exclusively to the top 1 percent of the income distribution. According to Forbes’s newly released ranking of the 400 richest Americans, the combined net worth of these 400 individuals, at $2 trillion, is higher than ever before. The price of entry to this exclusive club now stands at $1.3 billion, and the vast majority of these billionaires have seen their fortunes grow substantially this year.

These reports paint a troubling picture of an economy in crisis. Poverty is persistently high, income for the typical family is stagnant, and inequality is high and rising. Five years after the financial crisis, the economy is failing most Americans while delivering outsize rewards to a few wealthy investors. These are serious problems that policymakers must address.

But this week’s data deluge did include one piece of good news, depending on your perspective: The Congressional Budget Office, or CBO, released its long-term budget projections, and they have improved substantially over the past three years.

In 2010, when policymakers first decided to pivot from a focus on economic growth to an agenda of drastic deficit reduction, our long-term fiscal outlook was bleak. CBO’s most commonly used projections from that year indicated that debt would hit 100 percent of U.S. gross domestic product, or GDP, by 2023 and rise dramatically thereafter, reaching 185 percent of GDP by 2035.

Since then, as the Center for American Progress has explained, our nation’s fiscal outlook has improved dramatically due to a combination of legislated tax and spending changes and slower-than-expected growth in health care costs. This week’s CBO report bears this out; there is no longer a looming fiscal crisis.

The CBO now projects that debt as a share of GDP will decline for the next five years. Only then will the debt begin rising, and it will rise much more slowly than previously projected. Debt as a share of GDP will remain below current levels through 2025 and will not reach 100 percent of GDP—the level previously projected for the end of the current decade—until 2038.

You would think that Washington would see these improved projections as good news and as a chance to focus on more immediate problems that directly affect the lives of most Americans. Unfortunately, the conversation still seems to be stuck in the past, with conservatives in Congress pressing for even more spending cuts, including to programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which will further harm middle-class and low-income families.

The copious amounts of data released this week all confirm that the conversation in Washington is seriously out of touch. Although all the talk is of debt limits and government spending levels, the long-term debt trajectory has actually improved dramatically, even as the state of our economy continues to be incredibly troubling. Policymakers should pay heed to the new reality and recommit themselves to boosting economic growth and job creation, growing the middle class, and ensuring that growth is shared broadly, not just funneled to the wealthy few.

Kitty Richards is the Associate Director of Tax Policy at the Center for American Progress. Michael Linden is the Managing Director of the Economic Policy team at the Center.