While the drama and sportsmanship of the World Cup has captured the world’s attention for several weeks, an international gathering of a different kind is set to begin in Fortaleza, Brazil, on July 15. After attending the final soccer match at the invitation of Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff, the leaders of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, or the BRICS countries, will meet for their sixth summit.

The summit is likely to be more show than substance—but never underestimate the power of a good show. For a group that began as a mere Goldman Sachs acronym, the BRICS has slowly asserted itself as an economic entity. During this week’s summit, the group is likely to announce its own BRICS development bank with starting capital of at least $50 billion, and it is also cautiously wading into political territory.

What is the BRICS?

The BRICS began as BRICs—or Brazil, Russia, India, and China—an acronym coined by Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill as shorthand for the developing economies with high projected growth. The countries took this constructed association seriously and began meeting formally in 2006. South Africa joined the club in 2010.

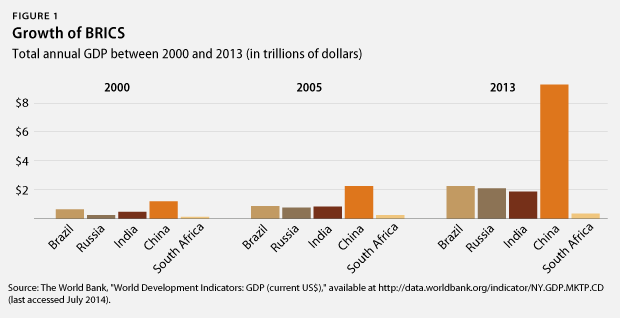

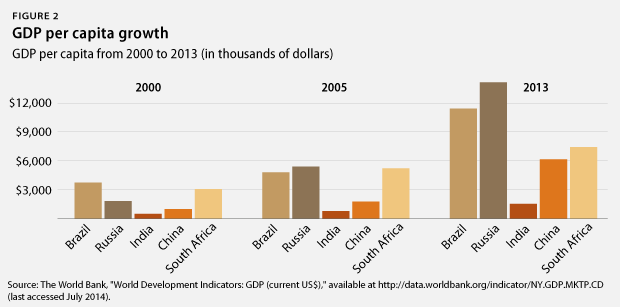

O’Neill’s optimism for the future of the BRICs has been mostly realized: These five countries have seen astounding growth over the past decade. For example, Russia’s gross domestic product, or GDP, per capita has increased almost eightfold since 2000, and China’s GDP has increased sevenfold and currently makes up about 12 percent of global GDP. In fact, the BRICS economies currently comprise 21 percent of global GDP.

But the BRICS has struggled with the significant economic and political differences among its members. The BRICS is not an alliance in the traditional sense; instead, the countries are a loose configuration of economic powerhouses that are aware of their economic strength but unsure of its implications or how best to wield their increasing power on the international stage. They share a suspicion of the U.S.-led global order and its institutions, such as the United Nations, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund, or IMF—all of which they see as unresponsive to their interests and desirous of their cash. But even this shared interest masks deep differences: China and Russia are both veto-wielding permanent members of the U.N. Security Council and are opposed to changing this structure to give permanent seats to their BRICS partners.

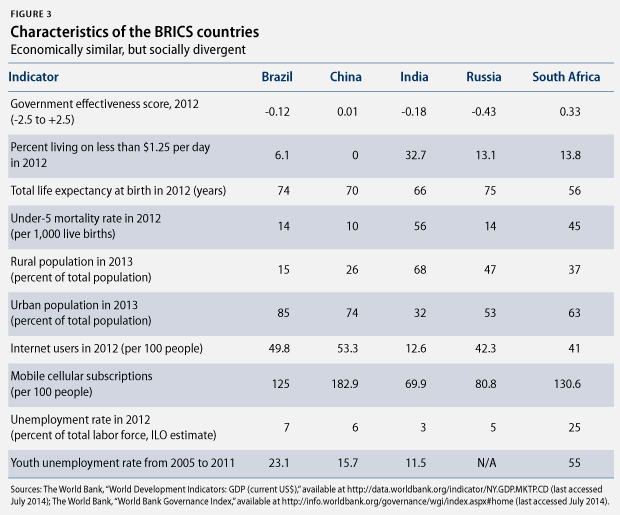

A closer look brings the differences between the BRICS countries into stark relief and unveils marked demographic differences and political and economic challenges. Alliances such as the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, the European Union, and even NATO are strengthened by comparable levels of economic growth and stability, similar governance structures, shared histories, and, often, shared borders. The BRICS countries are disparate in location and culture, have competing economic interests, and face a variety of challenges, including poverty; emerging—or nonexistent—democratic institutions; and regional concerns that do not always overlap. The countries have sparred over India and China’s territorial disputes, regional economic troubles in Latin America, and Russia’s conflict with Ukraine. These countries are not ranked closely in either the U.N. Human Development Index or the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators.

In an increasingly complex world with more powerful international actors and challenges ranging from pandemics to climate change to transnational terrorism, bringing together small groups of diverse actors on specific issues is not necessarily a bad thing, and countries can find strength in diversity. For example, BASIC—Brazil, South Africa, India, and China—is working to push its members’ climate agenda, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN, focuses on regional economic concerns. The BRICS countries are still deciding where they wish to focus and exert their joint effort, and their differences will shape the issues on which they are able and willing to focus their efforts.

Despite their significant differences, the BRICS countries appear to be seeking increased influence on the world stage through joint initiatives. What will that mean for this week’s meeting in Brazil?

What to look for at the BRICS summit

All eyes will be on India’s newly elected prime minister, Narendra Modi, as he attends his first BRICS summit, which will also be his first big multilateral appearance since taking office. His Brazilian hosts are especially keen to court him: Prime Minister Modi was elected with a large democratic mandate, and given that Brazil is more similar in size and political system to India than to the other BRICS countries, the Brazilians are likely keen to explore the possibility of closer ties.

But it is not just President Rousseff who will be seeking Modi’s time. Prime Minister Modi will arrive amid talk of his visit to Japan next month. This visit is aimed at bolstering the countries’ bilateral relationship, one that is increasingly important as China’s regional power continues to grow. Given the increasingly tense relationship between China and Japan and territorial disputes between China and India, the meeting between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Modi should be interesting. Both Modi and Xi have been quick to dismiss any perceived grievances, and a private meeting between the two has been arranged during the summit. They will likely be eager to downplay their differences and to emphasize the constructive cooperation between their two countries, but caution and unease could define the conversation and the bilateral relationship overall.

As Prime Minister Modi is fêted, Russian President Vladimir Putin is likely to be the outsider. As a group originally brought together on an economic basis, the countries’ political differences make joint action in noneconomic areas more difficult. In their biggest political play as a group thus far, the BRICS countries issued a joint statement following the annexation of Crimea. While President Putin sought a much more assertive, affirmative stance, the BRICS countries abstained from voting on the U.N. resolution on “the territorial integrity of Ukraine.” Instead, they issued a joint statement to condemn the international community for isolating Russia.

The headline of the summit is likely to be the announcement of a BRICS development bank to be headquartered in China. Each BRICS country will initially contribute $10 billion in capital, but remaining funding is still being debated. The announcement will come after many years of discussion and follows the BRICS countries’ initial declaration of interest in Durban, South Africa, in 2013. The bank would function similar to the way the World Bank does; much like the African Development Bank or the Asian Development Bank, the BRICS development bank has the potential to play a vital role in the provision of increased funding for infrastructure and key development needs.

But such a bank will likely take 5 to 10 years to begin operations. So while the announcement is symbolically important, it will have limited initial impact. How the bank is set up, the makeup and structure of its governing body, the rules and procedures—all of these details will need to be negotiated and then implemented, a challenging task both technically and politically.

Given the differences among the BRICS members, the negotiation process may be at least as important as the announcement of the bank itself. Negotiations will clarify the balance of power within the BRICS countries and the scope and scale of their cooperation. It looks as if China has won the debate over the location of the bank’s headquarters, but the other BRICS pushed back when China tried to inject another $50 billion on top of the $10 billion that each country is already contributing in return for majority shareholder status. Although the other BRICS countries seem just as keen as China to use the group to challenge U.S. dominance, they are no doubt wary of China’s outsized influence in a so-called G-2 world, in which the United States and China are the superpowers and the other nations are merely junior players.

Is the United States hitting a BRICS wall?

The U.S. relationship with the BRICS member countries has been strained by the National Security Agency, or NSA, scandal; disagreements about previous military actions in Libya and Iraq; and stalled reforms of the international financial institutions.

Downplaying the role of BRICS as an entity, the United States has instead engaged with BRICS members separately and through the G-20. This is reasonable, given the differences among BRICS countries—though the U.S. approach underestimates the important role that the group can play. Had O’Neill not coined the term BRICs, it is unlikely that several of the world’s largest economies would have issued a joint statement condemning international isolation of Russia in response to the invasion of Ukraine. Even this noncommittal response should make the United States take note of the increasing influence of the BRICS.

The United States should not view the BRICS as a threat, but instead ensure that the group does not become one by proactively improving its relationships with individual members of the BRICS and strengthening and reforming existing global alliances and institutions to make them more effective.

Potential next steps for the United States include:

- Welcome the announcement of a BRICS development bank as a valuable contribution to global economic growth and development. The bank has the potential to provide a crucial service by financing large infrastructure projects in developing countries, fulfilling a need that the U.S. supports. Steering their own bank will also force the BRICS countries to confront difficult questions about how to handle risk, conditionality, and governance, as well as offer the potential to share knowledge and lessons learned with the multilateral development banks.

- Improve and reinforce the existing international financial institutions. As a first step, the Obama administration should continue to work with Congress to pass the long-delayed IMF reforms. The reforms maintain U.S. veto power but give emerging-market economies a greater voice in return for providing more funding and taking on more responsibility. It is a fair deal and the best way to accommodate shifting power dynamics without destroying the existing structures of global cooperation.

- Reach out to BRICS countries; additional groupings, such as ASEAN; and other emerging economies, such as Mexico, Nigeria, Indonesia, and Turkey, to better understand their individual and joint interests and objectives in order to develop a shared vision for global cooperation in the 21st century.

In the face of a fragile global financial market, rising levels of inequality, the overwhelming and rapid flow of information and questions about its use, dispersed military threats from extremist groups, the effects of climate change, and concerns about resource scarcity, the current global governance system is starting to crack. Neither the BRICS nor any other group of countries offer an alternative to that system—in fact, their rise has depended upon its success. The crucial question for the United States is whether to try to shape the new global system or merely play at the margins. Restoring and revitalizing the global system, including investing in a dynamic set of partnerships and alliances and shoring up domestic support for them, is vital to managing the threats of the 21st century.

Molly Elgin-Cossart is a Senior Fellow with the National Security and International Policy team at the Center for American Progress.

The author would like to thank Annie Malknecht for her invaluable assistance in the production of this column, as well as Kayla Malone for her research assistance. She is also grateful for the comments provided by Homi Kharas, Varad Pande, and David Steven.