Anyone following education policy over the past several years has most likely read a headline along the lines of this: “Disgruntled New Teachers Leave the Profession in Droves.” Readers are led to imagine disillusioned and frustrated educators running out of school buildings, never looking back. Despite recent education policy stories that have reported new teachers leaving the profession in significant numbers—up to 50 percent by the fifth year in the profession—as well as two recent reports that relied on 10-year-old data, the picture since 2007 has been decidedly rosier: Fully 70 percent of beginning teachers stay in the profession for at least five years.

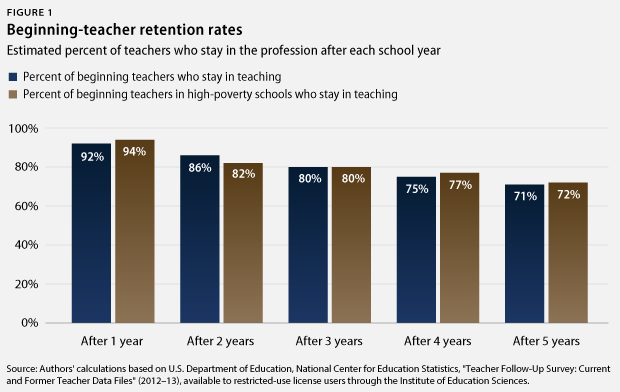

The Center for American Progress calculated this much-higher statistic of new-teacher retention using several national surveys from the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics. For a column on this topic earlier this year, we analyzed three of these surveys—the Schools and Staffing Survey from 2007-08; one of its follow-up studies, known as the Beginning Teacher Longitudinal Study, which followed new teachers over several years; and the Schools and Staffing Survey from 2011-12. We found that 87 percent of new teachers stayed in the profession for at least three years. Comparing the two Schools and Staffing surveys, we estimated that close to 70 percent of new teachers stayed for at least five years, a 20 percent jump over previous reports. The Department of Education released new survey data this past September—the 2012-13 follow-up study of the 2011-12 Schools and Staffing Survey. Using this dataset, we replicated the statistical method of researcher Richard Ingersoll—whose research is normally cited as the source of the 50 percent statistic—to again estimate that 70 percent of new teachers would stay for at least five years.

Not only do our analyses show that since 2007, new teachers have been staying in the classroom at dramatically higher rates than is commonly understood, but they also show that teachers in high-poverty schools—defined here as those with more than 80 percent of students eligible for federally subsidized lunches—are staying at statistically similar rates as all beginning teachers. Teachers find high-poverty schools to be among the most challenging work environments, and they are somewhat more likely to leave teaching after working in a high-poverty school than in a lower-poverty school. Our analysis, however, shows that beginning teachers in these settings display retention patterns similar to those of their counterparts in lower-poverty schools—at least over their first five years in the classroom.

A seemingly sizable jump in new-teacher retention between 2003 and 2007 begs the question: Why? For one thing, the media has summarized the existing research in a somewhat inaccurate way. Ingersoll and his colleagues’ estimates suggest that beginning-teacher retention rates are between 50 percent and 60 percent over the first five years of a teaching career. Researcher David Perda has shown—in his unpublished research cited by Ingersoll—that those rates were closer to the 60 percent end of the range. Perda’s analysis was based on the Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study that followed college graduates from 1993 through 2003. Between 2003 and 2007, there were not any major structural changes to the teaching profession that can explain the increase to 70 percent. Teacher salaries generally grew by less than the rate of inflation, and the economy was strong over this period. This uptick may have started before the Great Recession began at the end of 2007 and continued because of it, or it may have started in response to it. Nevertheless, we saw teacher retention rates this high several years after the recession officially ended in 2009. Clearly, there’s a need for more research to explore these issues.

Moreover, these national numbers mask local differences. Certainly, individual schools experience different levels of turnover—some more, some less. Across North Carolina, for example, teachers leave their districts at somewhat different rates, according to a report by the state Department of Public Instruction. While only 10 percent of teachers left North Carolina’s Catawba County Schools in 2013, 20 percent left Durham Public Schools. These local variations are important, and like the researchers in North Carolina, researchers across the country should identify explanations for them.

Of course, some attrition is good, as some teachers might find they are not a good fit for the profession. The nation should strive to retain effective teachers, as CAP and others, such as TNTP—a national education consulting and advocacy organization—have recommended, but we should not try to retain every teacher. Like any professionals, beginning teachers sometimes leave when they decide for themselves that teaching is not a good fit for them, when they get married, when they have kids, or when they move. The optimal level of teacher retention is not 100 percent. Given what is known about how much teachers improve their classroom practices during their first few years, the fact that more beginning teachers stay could actually mean that many more students today have access to more effective teachers. Again, we believe this is another important area where more research should be done, but we did not explore this question in this study.

Not withstanding the admittedly narrow focus of our study, the findings suggest that far more beginning teachers stay in teaching than has been reported elsewhere, and this is a promising development. This might mean that new teachers today are more satisfied with the teaching profession as a whole, as well as with their own working experiences in schools. Ultimately, we serve our students best when we work to retain the best teachers, no matter their experience levels.

Robert Hanna is a Senior Education Policy Analyst at the Center for American Progress. Kaitlin Pennington is a Policy Analyst on the Education Policy team at the Center.