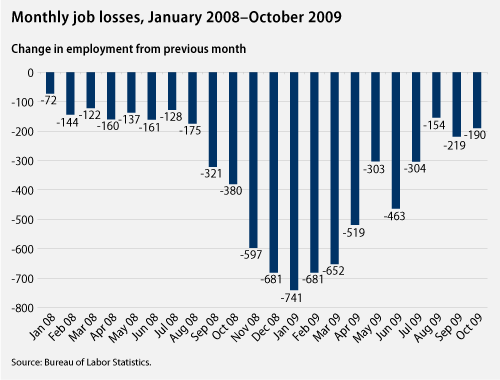

How does a government go about creating jobs in a recession? It’s a question on many minds in Washington because, although the bleeding has slowed, we’re still hemorrhaging jobs at a clip of just under 200,000 per month. And with job losses at 7.3 million since the recession began, that’s draining an already seriously depleted body.

Of course, the government has already done a lot. The Federal Reserve has played a major part in dealing with the financial sector disaster and in its traditional role as the overseer of U.S. monetary policy. The Fed is doing all it can, lowering and then maintaining the federal funds rate in the vicinity of 0 percent to make credit as cheap as possible so that it is easier for consumers to spend and business to invest to spur the economy and create jobs.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act in February was also a giant step. Considering the steep downward momentum that the economy had at that time, it’s hard to know now bad things would have gotten without it. The pace of job loss, running at over 500,000 jobs per month through April could have continued many months more or even accelerated. There is little serious doubt that we would not have seen such positive signs—good economic growth in the third quarter of this year and some states starting to show hints of job growth—without ARRA.

Yet the recession was far worse than many analysts—including those in the Obama administration and Congress—recognized at the beginning of 2009. The worst numbers of the then-year-old recession hadn’t appeared yet when the big decisions were being made. ARRA was scaled to douse a six-alarm fire, but it got poured onto a 10-alarm blaze. As the various components of ARRA have come fully on line—and job losses have persisted—it’s become obvious that something more needs to be done. The need for action is unequivocal, ARRA and many historical precedents show that public interventions can have a major positive impact and the time for action is now.

One place that we shouldn’t look for new good ideas for job creation is ideologically blinkered conservatives. The purists reject the idea that government should take any special action during hard times to save or create jobs. Yet that view doesn’t stop them from using the public cry for action as an opportunity to offer the same answer that they offer for almost everything—cut taxes for the wealthy and corporations, and reduce the size of government. That crowd has been rebutted many times, and we’ll skip that exercise this time. Tax cuts may play a role, but the kind this “supply-side” crowd favors would be a complete waste of money when it comes to creating the jobs when we need them.

Pragmatic progressives offer a number of ways to go in seeking job creation. There are three basic approaches to job creation within the domain of the president and Congress, leaving aside the Federal Reserve’s domain of monetary policy:

- Increase demand in the economy.

- Directly create government or government contract jobs.

- Create private sector jobs by offering incentives to businesses.

Each has its pluses and minuses and a role to play. Let’s consider each in turn.

Increasing demand in the economy

Increasing demand to escape a recession is a tried-and-true approach. It is based on an intervention in the lifecycle of a recession. Businesses, faced with a lack of customers or more restrained customers, lay off workers and cut back on investments in a recession. This, of course, means fewer customers as the unemployed restrain their consumption, and businesses buy less as well. This forces businesses to make more cutbacks. And the cycle continues to drive the economy down. That’s where government steps in by taking actions that include both direct spending to offset the drop in private consumption, and helping consumers and businesses ramp up their spending. When demand for goods and services begins growing, businesses need to hire and become more confident in hiring and investing. The cycle is reversed and the economy turns.

Examples of direct spending in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act that created demand in the economy and precipitated additional hiring while slowing job losses this year include ramping up infrastructure spending on roads and bridges and making investments in energy efficiency and health technology.

ARRA also sought to increase demand by putting more money in the pockets of the public and businesses. The premise of these provisions is that the more consumers have, the more they’ll spend. Expanded unemployment benefits in ARRA, for example, put money in the pockets of people who—given their difficult circumstances—were likely to have to spend what they received. ARRA also included substantial tax cuts, notably the Make Work Pay tax credit that resulted in lower tax withholding from pay checks for much of this year. This helped make progress toward economic recovery to the extent that it added to take-home pay and boosted consumer spending. But to the extent this tax credits went into savings, it has not helped. Savings can be good for an economy in the long run, but for pulling an economy out of a downturn they’re not helpful.

Much of the spending that results from these efforts to increase demand in the economy is, of course, spending that would have eventually happened anyway. The roads being repaired, the cars bought because of the Cash-for-Clunkers program—those roads would have been repaired and those cars eventually bought. But that is, in fact, the idea. The purpose of boosting demand during the downturn is to get the economy growing, not to permanently increase consumption at the expense of savings. Making consumption happen now, when it is needed to give the economy a jolt, and taking it from a future time when the economy is operating normally, is exactly the idea.

This is also why it is fine for the government to run deficits to pay for all this consumption in the short term. Yes, the borrowed money will have to be paid back. But it will be paid back when the country can afford it, when the economy is growing and tax receipts are up—in short, when the strategic use of that borrowed money now has launched us back onto a healthy economic path. The nation will have to consume less in the future to pay it back—but we’ll still have the benefit of that spending in the form of the goods and services bought and in the form of a recovered economy.

Although it is fine to be running these deficits now, it’s important to note that a relatively small portion of the deficits run in 2009 were the result of ARRA. The increase in the deficit from 2008 was mostly due to the recession’s automatic impact on the federal budget, especially lower tax collections and the continuing rise in health care and other costs. About half of the deficit was due to the drop in tax collections and half to spending increases. This includes the impact of ARRA. The tax revenue declines were, however, four times as large as ARRA spending provisions.

The evidence that the Recovery Act worked is tangible. All but the most intransigent give a good portion of the credit to ARRA for the shift from an economy that shrunk at an average annual rate of 2.4 percent in the first six quarters of the recession to an annual growth rate of 3.5 percent in the third quarter of 2009.

The jobs picture has likewise improved—moving from jobs losses of over 500,000 per month from November 2008 through April 2009 to losses hovering around 200,000 since August.

This improvement is for the most part not because of the jobs you hear about—the construction worker on the road project or the contractor weatherizing a home. It is because of the jobs that haven’t been lost, or that have been created, which are the result of the demand created by ARRA in the economy—demand that has spread to businesses and given them the confidence to retain employees or add them. The connection of these jobs to ARRA is not always easy to see, but it’s there.

Boosting demand to spur economic growth, reverse the downward path of the economy, and create jobs as a by product is an effective way to create jobs. But the jobs created are hard to count, and once that approach has started to work its magic, there’s still a risk of a “jobless recovery.” We are, after all, still losing jobs. Even if the economy were to start creating jobs very quickly it’s going to take a long time to recover the 7.3 million jobs that have been lost in this extraordinary recession—let alone create jobs for the well over a million additional job-seekers who enter the workforce every year due to normal population growth. This has added up to there currently being 15.7 million unemployed.

Even extraordinary job growth leaves us with a long path back. The peak month for job growth in the last 20 years was September 1997, when 508,000 net jobs were added. Even if we hit that extraordinary peak for every month of 2010—which is exceedingly unlikely—we’d only create 6.1 million jobs. Getting half that many would be considered a year of strong job growth.

Joblessness has also moved from being a symptom to being a contributing factor in the recession. Unemployment itself is a drag on the economy—the unemployed are forced to reduce spending, which hampers economic growth. Government action focused on boosting demand is absolutely necessary to get the economy moving. But there’s also a time to directly address job creation.

Directly saving and creating jobs

There are two basic approaches to directly saving and creating jobs: the government employs workers, or pays companies to employ workers; or and the government creates incentives for employers to employ workers.

Public-sector job creation

Having the government directly hire workers is incontrovertibly effective. Part of what ARRA accomplished was to help the government keep people on its payroll. Much of the funds given to state and local governments, in particular, allowed them to avoid laying-off state and municipal workers. Additional layoffs would have been a certainty had those funds not been provided given those governments’ absolutely dire fiscal situations in the face of falling tax revenues, and constitutional and political barriers to their borrowing.

Addressing job creation through direct government hiring has a number of advantages. First, of course, is that there isn’t any question about whether the jobs are being saved or created. The people are there, in public service.

Second, the funds used to employ people can be put to public use. No one wants to use taxpayer dollars to employ people in digging and then filling up ditches. There is much to be done in the nation—whether it’s cleaning up parks, adding teachers to schools, or providing home health care to the elderly and quality child care to those in need—that’s useful and productive These are jobs that serve a public purpose. Even if the jobs are temporary, they produce a good while they last—often a lasting good.

Third, the programs can be moved to where they are needed most. Almost every state in the country is hurting economically right now, but the levels of pain vary from state to state and community to community. Targeting hiring in areas hit hardest most can create the most bang for the buck.

It is important to note that this hiring is not purely an act of generosity. The temporary boost in public hiring helps everyone by:

- Alleviating the drag on the economy from unemployment.

- Putting cash in workers pockets that they can spend.

- Improving public services.

These important public gains also relieve pressure on the labor market so that those who are seeking employment in the private sector are not competing with so many others. There are currently more than six unemployed workers for every job available.

Private-sector job creation

The other approach to direct job creation is offering incentives to the private sector to retain or hire more workers. The most obvious way to do this is to offer subsidies to private employers. Ideas such as President Carter’s New Jobs Tax Credit and proposals for payroll tax “holidays” or rate reductions fit in this category.

There is absolutely no question that private-sector hiring in the end will bring back the labor market. But that doesn’t mean the best way to make that happen is to offer corporations subsidies to hire people. The fundamental problem with this approach is this—when businesses don’t believe hiring is in their best interests or investments are the right move then government subsidies need to be substantial to make them take the risks involved in hiring and investing.

Economists predict that private-sector hiring will rise if the marginal cost of hiring drops a tad, but it’s not clear that those making hiring decisions think of things that way. Such incentives no doubt have an impact—but their effectiveness is seriously constrained by the market conditions in which businesses are operating. And such incentives are hugely inefficient. Most of the money paid out in subsidies goes to businesses that would have employed people anyway, even without the subsidy.

The best way to boost private sector employment is not by directly subsidizing jobs per se, but indirectly. Spurring demand, as described above, causes businesses to save or create jobs and we get something for it. Government hiring contributes to demand as the hired workers spend, but dealing with government fiscal problems also helps the private sector directly. Contractors are hired and goods purchased that require businesses to increase their output and hire.

Conclusions

There is a desperate need to continue to focus on creating jobs. But, as the math above shows, we’re not going to be out of the jobs hole for a number of years. A mix of policies is therefore appropriate to help get the country back on track. ARRA spending will still be substantial in 2010, playing its role of spurring demand. That is essential, and projections for 2010 suggest that policy makers could do worse than offering more of the same. But public job creation is also needed.

Public job creation is the most reliable way to save and create jobs. There are a number of ways to do this, but probably the single most worthwhile step that could be taken is to provide more assistance to state and local governments so that their fiscal problems don’t become even more of a national economic and jobs problem. This is an essential step that the federal government should take as soon as possible.

We also can’t forget that the United States will need jobs in the years beyond 2010. One of the features of ARRA was that it included several measures that were a little slower to provide help, but which constituted important investments in the future that will pay dividends for years to come. The investments in energy, health technology and infrastructure stand out. Some are in the form of incentives to private business.

It would be a good investment for the federal government to build on those efforts, targeting them to create jobs in 2011 or 2012. We will still need the jobs at that point, and should be creating important building blocks for the economic growth of the future.

Michael Ettlinger is Vice President for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress. To read more of the Center’s economic analysis and policy recommendations please go to the Economy page on our website.

See also: