Introduction and summary

In March 2019, a group of mothers working for Amazon—known as “Momazonians”—organized an information-gathering and advocacy campaign that urged the company to provide a backup child care benefit. The group of nearly 2,000 Amazon employees with young children argues that a lack of affordable child care has prevented talented women from progressing in their careers. These mothers are “tired of seeing colleagues quit because they can’t find childcare.”1 The Momazonians are calling on Amazon to subsidize a backup child care option for when their primary child care arrangement falls through, similar to the benefits offered by its peers such as Apple, Microsoft, and Google. This employee-led effort demonstrates the clear connection between access to affordable, quality child care and labor force participation—especially for mothers. However, employers cannot solve the nation’s child care crisis alone, and a few days of backup child care do not meet the needs of parents who must coordinate and pay for full-time year-round care.

Today, many families with young children must make a choice between spending a significant portion of their income on child care, finding a cheaper, but potentially lower-quality care option, or leaving the workforce altogether to become a full-time caregiver. Whether due to high cost, limited availability, or inconvenient program hours, child care challenges are driving parents out of the workforce at an alarming rate. In fact, in 2016 alone, an estimated 2 million parents made career sacrifices due to problems with child care.2

Child care challenges have become a barrier to work, especially for mothers, who disproportionately take on unpaid caregiving responsibilities when their family cannot find or afford child care.3 In a 2018 survey conducted by the Center for American Progress, mothers were 40 percent more likely than fathers to report that they had personally felt the negative impact of child care issues on their careers.4 Too often, mothers must make job decisions based on child care considerations rather than in the interest of their financial situation or career goals.

There is a growing awareness of the links among access to child care, parental employment, and overall economic growth. Businesses rely on employees, and employees rely on child care.5 When problems with child care arise, parents must scramble to find alternative options—or miss work to care for their children. For millions of parents, that insecurity can mean working fewer hours, taking a pay cut, or leaving their jobs altogether.6 American businesses, meanwhile, lose an estimated $12.7 billion annually because of their employees’ child care challenges.7 Nationally, the cost of lost earnings, productivity, and revenue due to the child care crisis totals an estimated $57 billion each year.8

This report highlights the relationship between child care and maternal employment and underscores how improving child care access has the potential to boost employment and earnings for working mothers. Based on new analysis of the 2016 Early Childhood Program Participation Survey (ECPP), it demonstrates how families are having difficulty finding child care under the current system and how lack of access to child care may be keeping mothers out of the workforce. The report then presents results from a national poll conducted by the Center for American Progress and GBA Strategies, which asked parents what career decisions they would make if child care were more readily available and affordable. Finally, the report outlines federal policy solutions that are crucial to supporting mothers in the workforce.

New ECPP findings demonstrate that a mother’s employment is closely tied to her family’s ability to find child care, while the CAP poll finds that with access to more reliable and affordable child care, mothers say they would take steps to increase their earnings and advance their careers. (See Appendix for data sources and methodology)

Key findings include:

- Half of U.S. families reported difficulty finding child care.

- Mothers who were unable to find a child care program were significantly less likely to be employed than those who found a child care program, whereas there was no impact on fathers’ employment.

- In the CAP survey, mothers said that if they had access to more affordable and reliable child care, they would increase their earnings and progress in their careers by finding a higher-paying job, applying for a promotion, seeking more hours at work, or finding a job in the first place.

The current child care system in the United States is broken. The United States must prioritize the needs of millions of working families and take steps to keep mothers in the workforce through investing in policies to support access to affordable, quality child care.

Working mothers and the child care crisis

Child care is necessary for parents—particularly mothers—to work and earn an income, yet it has become an increasingly crushing expense for families with young children. Over the past two decades, the cost of child care has more than doubled,9 while wages have remained mostly stagnant.10 Many parents find that child care expenses consume most of their paycheck, and some decide to leave the workforce as a result.11 Typically, mothers are the ones who make that tradeoff.

Research supports that high child care costs and limited financial assistance are driving mothers out of the workforce. Over the past two decades, women’s labor force participation in the United States has stalled while other major developed nations have seen continued growth.12 The high cost of child care is partly to blame: One study found that the rising cost of child care resulted in an estimated 13 percent decline in the employment of mothers with children under age 5.13 What’s more, the nation’s failure to implement policies that support mothers to enter and remain in the workforce—such as child care and paid family leave—explains about one-third of the decrease in women’s labor force participation when comparing the United States with 22 other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries.14

Policies aimed at alleviating the burden of paying for child care have been shown to promote mothers’ participation in the labor force. A growing body of research confirms that policies that help reduce the cost and increase the availability of early childhood education programs have positive effects on maternal labor force participation and work hours.15 Additionally, a recent CAP study found that since Washington, D.C., began offering two years of free universal public preschool in 2009, the percentage of mothers with young children participating in the labor force increased by 12 percentage points—10 of which were attributable to universal preschool.16

Expanding mothers’ access to child care and other workplace supports is vital, as American families are increasingly relying on mothers’ incomes. Almost 70 percent of mothers are in the labor force, and in 2015, about 42 percent of mothers were the sole or primary breadwinners in their homes.17 Black and Latina mothers work at even higher rates and are more likely to be the primary breadwinner in their households than white mothers, with 71 percent of black mothers and 41 percent of Latina mothers serving as the primary economic support for their families.18 At the same time, women are disproportionately working in low-wage jobs with nonstandard hours and inconsistent schedules.19 Many of these mothers struggle to find affordable child care that aligns with their work schedules and is available during evenings and weekends.20 Child care challenges, coupled with low-wages and irregular schedules, make it difficult for many mothers to stay in the workforce—whether full or part time.

Child Care Development Block Grant and Head Start

The two largest federal programs that currently provide free or subsidized child care—The Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) and Head Start—are targeted toward low-income families with young children. The CCDBG is the largest source of federal funding for child care assistance and funds state-administered child care subsidies for low-income families. However, just 15 percent of eligible families receive subsidies through the CCDBG, and in most cases, the subsidy amount is too low to support the cost of high-quality child care.21

Head Start delivers high-quality early education, as well as comprehensive health and social services, to approximately 1 million low-income children and their families each year. It serves about one-third of eligible 3- to 5-year-olds, while Early Head Start serves 7 percent of eligible children under age 3.22

These programs have demonstrated benefits for promoting maternal labor force participation and positive child outcomes.23 Due to their targeted nature and chronic underfunding, however, only a small portion of families who need assistance paying for child care receive it.

Moreover, making job changes or leaving the workforce due to problems with child care can have tangible consequences for families’ economic security and mothers’ long-term earnings. Caregiving obligations that interfere with parents’ ability to work can drive families with young children toward financial hardship; in fact, this is a contributing reason that half of young children in the United States live in low-income families.24 In total, American families lose out on an estimated $8.3 billion in lost wages each year due to lack of child care.25 Taking even a short time away from work is consequential: An analysis from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research found that over a 15-year period, women who took just one year off work had earnings that were 40 percent lower than women who did not take time off.26 Beyond wages, the cost of leaving the workforce can follow mothers for years, as it can also lead to lost retirement savings and benefits.27

How the current child care system fails working families

This section outlines key findings from the author’s analysis of the 2016 Early Childhood Program Participation Survey (ECPP)—the most recent year of the survey available—exploring families’ experiences finding child care and how they relate to mothers’ employment. The ECPP includes data from 5,837 children and is a nationally representative survey, representing 21.4 million children between birth and age 5. (See Appendix for methodology)

Half of families report difficulty finding child care

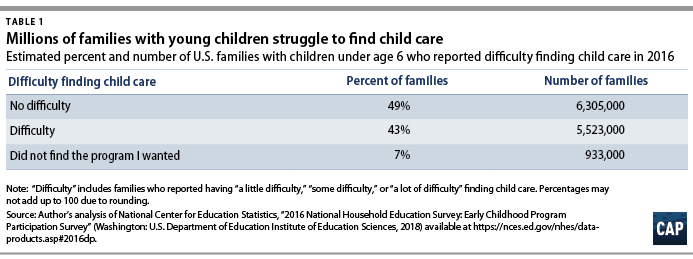

U.S. families with young children are having difficulty finding child care to meet their needs. This analysis finds that half of families who looked for child care in 2016 reported difficulty finding it, and nearly 1 million families never found the program they wanted. (see Table 1)

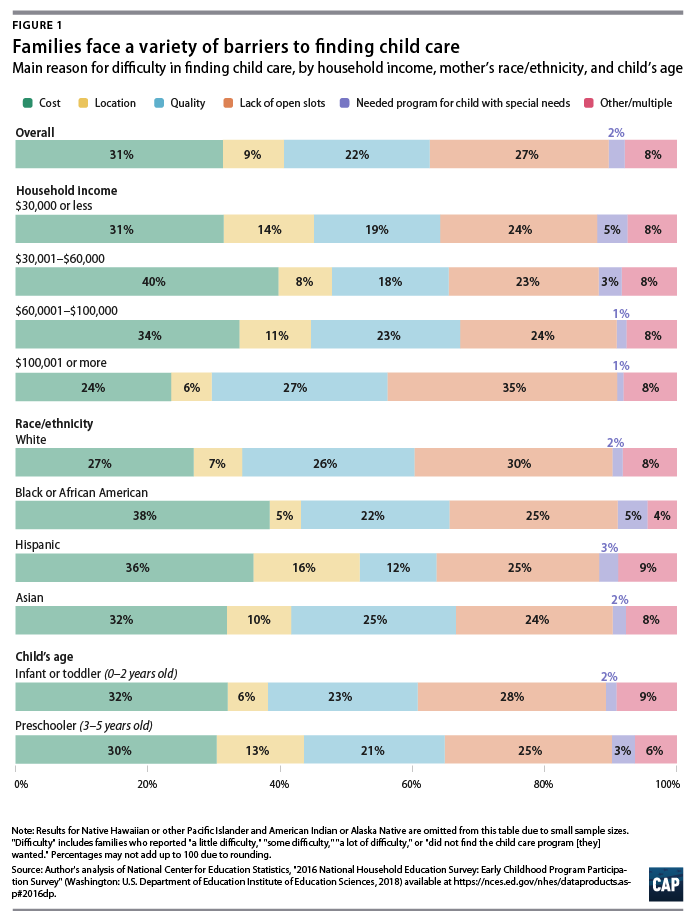

Families’ primary reasons for difficulty finding child care included cost, at 31 percent; lack of open slots at 27 percent; and quality, at 22 percent.28 (see Figure 1) These findings align with research highlighting the range of challenges that parents face accessing child care. While the cost of child care varies substantially by state and child care setting, the national average cost of care for one child in a center amounts to about $10,000 per year—which far exceeds what most families with young children can afford to pay.29 Many families struggle to find a viable child care provider in the first place: A nationally representative survey found that two-thirds of parents say they have “only one” or “just a few” realistic child care options for their child. Moreover, a CAP analysis of child care providers across the country found that half of Americans live in a child care desert, where there are few options for licensed child care at any cost.30

When parents cannot find a child care program, they often turn to relatives to provide care. Among families who reported that they did not find their desired child care program, most decided not to use child care—64 percent—or used care from a relative—24 percent—typically the child’s grandparent.31 Meanwhile, families that ultimately found child care predominately reported using a child care center. This finding suggests that relative care may be filling a gap where the licensed child care market is falling short of meeting working parents’ needs.32

Low- and middle-income families, families of color, and parents of infants and toddlers have an especially hard time finding care

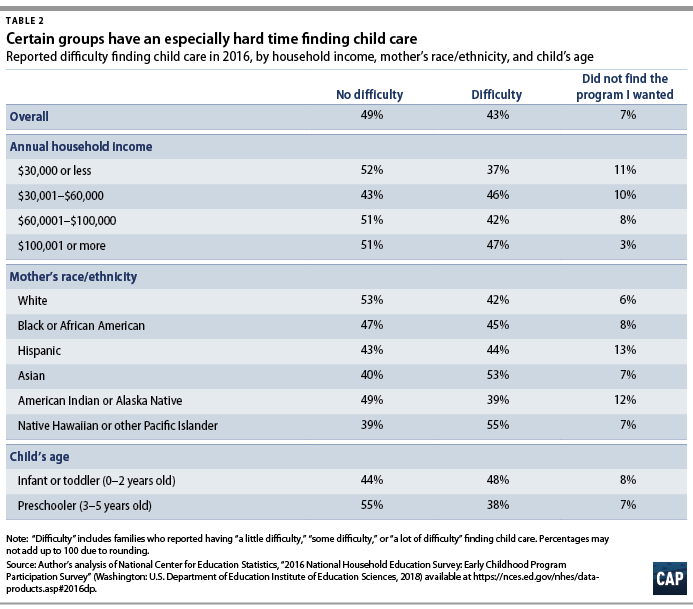

Certain families disproportionately face barriers to accessing child care. The 2016 ECPP survey shows that low- and middle-income families, families of color, and parents of infants and toddlers struggle to find child care, as well as report at high rates that they were unable to find their desired child care program. (see Table 2) Families also cite a variety of reasons for having trouble finding care that shed light on how the current child care system is failing to meet families’ diverse child care needs.

Household income

Overall, families are having difficulty finding child care regardless of their household income, with about half of families across income brackets reporting some degree of difficulty. However, families with incomes of less than $100,000 per year were significantly more likely than higher-income families to say that they were ultimately unable to find the child care program they wanted. (see Table 2)

Families earning less than $100,000 per year identified cost as the primary barrier to finding care, while families in the highest income quartile cited quality concerns and limited slots as the main reasons for difficulty. With the cost of child care amounting to thousands of dollars each year, low- and middle-income families are increasingly priced out of the child care market and struggle to find a program that they can afford. Lower-earning families were also more likely to cite location as a reason for difficulty, which is likely due to a lack of child care infrastructure in lower-income neighborhoods—and perhaps, barriers to accessing affordable and reliable transportation.33 Together, these factors can constrain child care choices for low- and middle-income families. Higher-income families cite lack of slots and quality as their primary challenges likely because there is greater competition for a limited number of slots in high-quality programs.

More than half of families in the lowest income quartile said that they had no difficulty finding child care—a rate comparable to that of the highest-earning families. This could reflect access to means-tested programs such as Head Start, or the fact that lower-income families turn to relatives and friends for child care and therefore may not have to undergo an extensive search to find someone to care for their child. However, the lowest-earning families also reported that they were ultimately unable to find their desired child care program at about three times the rate of the highest-earning families. This could suggest that Head Start and child care subsidies serve some low-income families well, but that in the absence of that assistance, other families find themselves unable to find an affordable option that meets their needs.

Mother’s race and ethnicity

Overall, mothers of color reported higher levels of difficulty finding child care than white mothers. Notably, Hispanic and American Indian or Alaska Native mothers were more than twice as likely as white mothers to say that they did not find their desired child care program. Hispanic mothers cited “location” as the top reason for difficulty at about two times the rate of white and black mothers, which is consistent with the fact that Hispanic families are also more likely than white or black families to live in a child care desert.34 Black mothers were significantly more likely than white mothers to cite cost as the top reason for difficulty. For a typical black family, the average annual cost of center-based child care for two children amounts to 42 percent of median income, so it is not surprising that black mothers report cost as a major barrier.35

Infants and toddlers

Families with infants and toddlers—children under age 3—are significantly more likely to encounter difficulties finding care than families with 4- and 5-year-olds. Fifty-six percent of families with infants and toddlers reported some degree of difficulty finding care, compared with 45 percent of preschool-aged children. Families with infants and toddlers also reported that “lack of available slots” was the primary reason for difficulty at higher rates than families of preschool-aged children. (see Figure 1) This is consistent with a recent CAP analysis that showed a severe undersupply of child care for infants and toddlers, with infants and toddlers outnumbering available child care slots by more than 5-to-1 overall, and by 9-to-1 in rural areas.36 On the other hand, families with preschoolers were significantly more likely than families with infants and toddlers to report “location” as their top reason for difficulty. This may be because preschool programs tend to be in central locations such as public schools, while home-based infant and toddler care is often available in local neighborhood settings.

Mothers who do not find child care are less likely to be employed

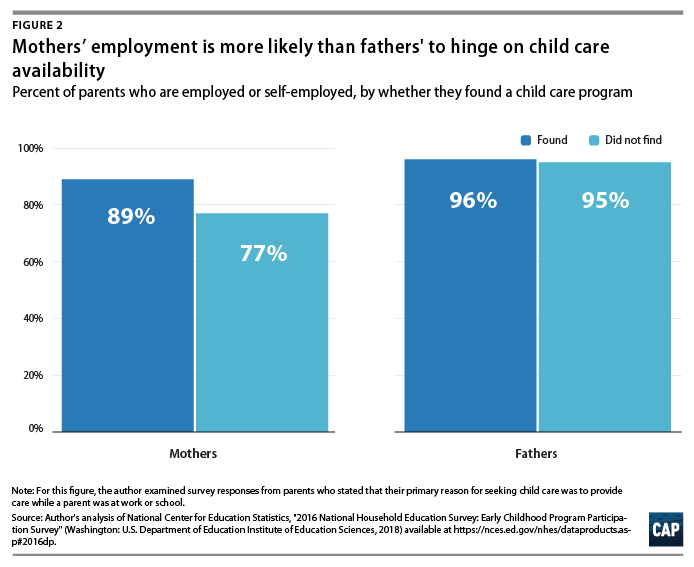

Finding a child care program appears to influence mothers’ ability to work, although there is no impact on fathers’ employment. Among families who sought child care so that a parent could work, mothers were significantly more likely to be employed if their family found a child care program. (see Figure 2) Eighty-nine percent of mothers who found a child care program were employed, compared with 77 percent of mothers who did not find a child care program.37 Whether or not a family found child care had virtually no effect on the likelihood that fathers were employed, as about 95 percent of fathers were working in either case.

Single mothers experienced steep drops in employment when they were unable to find a child care program. Specifically, the employment rate fell from 84 percent among single mothers who found a child care program to 67 percent among those who did not. For comparison, employment among mothers in two-parent households decreased from 90 percent to 84 percent when the mother did not find care. Single mothers are often both the primary earner and caregiver in their households, making child care access a necessity for these mothers to remain employed. Without access to formal child care, single mothers typically rely on a patchwork of care from family and friends, which can be difficult to secure consistently. A growing body of research has demonstrated that child care assistance has a substantial impact for single mothers. In fact, child care subsidy receipt and kindergarten enrollment are associated with higher rates of employment and enrollment in job training or education programs among single mothers.38

These findings should come as no surprise. Child-rearing responsibilities disproportionately fall on mothers, so problems with child care most frequently result in mothers making career sacrifices.39 While some families prefer for a stay-at-home parent to care for children, most families rely on two paychecks or the single parent’s paycheck to make ends meet. In the absence of viable child care options, mothers are often forced to modify their work schedules, settle for lower-quality care, or leave the workforce altogether—a decision that can jeopardize their family’s financial security.

Investing in child care would support working mothers, their families, and the nation’s economy

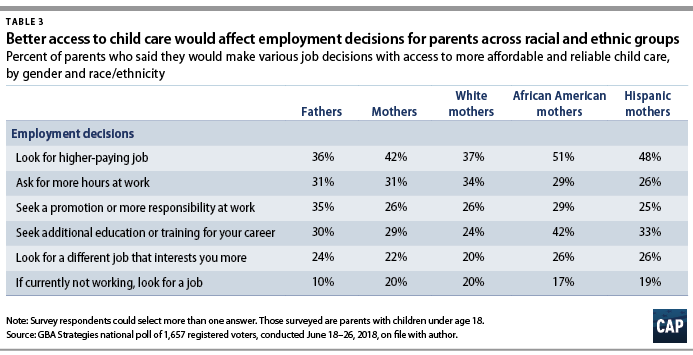

The current state of child care in the United States is creating a financial squeeze for working families and driving some mothers out of the labor force. Yet when asked to envision a world in which they had affordable, reliable child care, mothers overwhelmingly said that they would make changes to increase their earnings and seek new job opportunities. Results from a nationally representative poll conducted by CAP and GBA Strategies in June 2018 suggest that increasing access to affordable and reliable child care could give mothers the flexibility to pursue opportunities that can increase earnings and even allow them to advance at work. (see Table 3)

Mothers say they would increase their earnings and seek new job opportunities if they had better access to child care

The most common changes mothers said they would make were looking for a higher-paying job, at 42 percent, and asking for more hours at work, at 31 percent. (see Table 3) This finding likely reflects the fact that many mothers are earning low wages. Nationally, 1 in 5 working mothers with a child age 3 or under work in a low-wage job, and women represent about two-thirds of the low-wage workforce.40 For these mothers in particular, child care costs consume much of their take-home pay. Additionally, child care availability often dictates when and where mothers can work, as many mothers decide to work during nonstandard hours or take on a less demanding job so they can care for their children.41 Alleviating the burden of paying for child care could free up mothers to pick up additional shifts, take on more hours at work, or seek a higher-paying job—decisions that would translate into critical income.

For women of color, the survey findings suggest that child care access could have an even greater effect on employment and wages. More than half of African American mothers, and 48 percent of Hispanic mothers reported that they would look for a higher-paying job if they had better child care access. (see Table 3) Given that mothers of color are overrepresented in low-wage work and experience a significant wage gap when compared with white men—due to the compounded effects of gender and racial discrimination—these findings highlight how making child care more affordable could support mothers of color to find higher-paying jobs and increase their overall economic security.42

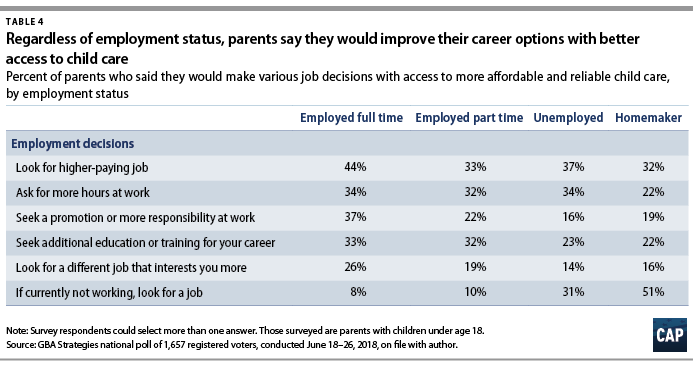

According to the poll, slightly more than half of respondents who identified as homemakers said that they would “look for a job” if they had access to more affordable child care. (see Table 4) With an estimated 6.7 million stay-at-home parents in the United States—the vast majority of whom are mothers43—this finding suggests that millions of women might join the labor force if they had access to affordable and reliable child care.44 In fact, they may prefer to work: Previous research from the Pew Research Center confirms that a growing share of mothers say that they would like to be working either part or full time.45

One-third of parents in part-time work said that they would ask for more hours at work if they had more affordable and reliable child care. (see Table 4) For many parents, that could mean boosting their earnings, transitioning from part-time to full-time work, or moving to a job that provides important benefits and workplace supports.46

Greater access to child care would promote family economic security and spur economic growth

Overall, paying less out of pocket for child care, coupled with mothers’ increased ability to work, would help promote greater family economic stability and, in turn, child well-being. In addition to child care, families with young children face many expenses associated with raising a child, often at a time when parents are early in their careers and financially vulnerable.47 Policies that help cover the cost of child care enable parents to use more of their earnings for other necessities and can reduce the number of children living in families that are struggling to make ends meet. Ensuring that all children have access to the supports, resources, and stability they need to thrive sets them on a path to healthy development and positive long-term outcomes such as increased educational achievement and consistent employment.48

Beyond the benefits to families, affordable child care is critical to expanding and sustaining the nation’s workforce and growing the economy. Providing child care assistance to all low- and middle- income working families would enable an estimated 1.6 million more mothers to enter the workforce.49 Another estimate posits that capping child care payments at 10 percent of a family’s income would yield $70 billion each year and increase women’s labor force participation enough to boost U.S. gross domestic product by 1.2 percent.50 Supporting access to child care would also save employers money on lost revenue associated with losing parent employees due to child care problems, as well as the costs to train and hire new employees.51

Policy recommendations

Although employers have a role to play in establishing family friendly benefits, and states have been making incremental progress to improve access to child care, federal action is necessary to ensure that all families have access to comprehensive work-family policies.52 Investments of this nature have support from voters across the political spectrum, with 90 percent of Democrats, 70 percent of independents, and 70 percent of Republicans saying that they would support efforts in Congress to increase funding for child care assistance and to expand access to early learning.53

Congress should enact the following policies to increase access to child care and support working mothers.

Increase funding for the Child Care and Development Block Grant

The Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) is the largest source of federal funding for child care assistance. Although child care is a critical support for children and families, the CCDBG has been so underfunded that just 1 in 6 eligible families actually receive child care subsidies.54 In fiscal years 2018 and 2019, Congress included the largest-ever funding increase for the CCDBG, which will provide states with critical resources to expand access to child care assistance and improve child care quality.55 While this increase is an important first step toward supporting the nation’s chronically underfunded child care system, this funding must be sustained and further increased to achieve meaningful and lasting change.

Pass the Child Care for Working Families Act

The Child Care for Working Families Act (CCWFA) is the boldest and most comprehensive proposed child care legislation to date. The CCWFA would increase access to reliable, affordable child care for most low- and middle-income families, limiting families’ child care payments to 7 percent of their incomes on a sliding scale.56 Under this bill, families earning the median income in every state would not spend more than $45 per week on child care, and approximately 3 in 4 children from birth to 13 years old live in families that would be income-eligible for assistance.57 Passing the CCWFA to make child care more affordable would enable an estimated 1.6 million parents to enter the workforce.58 The bill is also projected to create an additional 700,000 jobs in the predominantly female early childhood education sector and guarantee a living wage for early educators.59

Address the nation’s child care deserts

Half of Americans live in child care deserts, where there is an inadequate supply of licensed child care.60 Families living in rural areas, immigrant families, and Hispanic and American Indian or Alaska Native families disproportionately live in child care deserts; in these areas, fewer mothers participate in the labor force.61 Investments in the nation’s child care system must include targeted efforts to build the supply of licensed child care in these underserved child care deserts. Moreover, child care must be incorporated into any national infrastructure investment, as it is a necessary component of supporting workers and the economy.

Pass progressive work-family policies

Comprehensive paid family and medical leave, paid sick days, and fair scheduling standards are critical for supporting mothers in the workforce. Research has shown that having access to paid leave increases the likelihood that mothers will return to work after a child is born,62 as well as the chances that they will return to the same or higher wages than they were earning before they gave birth.63 The Family and Medical Insurance Leave (FAMILY) Act would offer up to 12 weeks of paid leave each year to qualifying workers who need to take time off for the birth or adoption of a new child, serious illness of an immediate family member, or a medical condition of their own.64 Paid sick days are also vital for mothers who may need to take time away from work to care for themselves, a sick child, or an ailing loved one. A comprehensive national paid sick days law, such as the Healthy Families Act, would set a national standard for qualifying workers to earn up to seven paid sick days a year.65 Finally, with many workers facing unpredictable and unfair work schedules, a national policy that sets minimum standards around scheduling practices would help workers—especially mothers—manage work and family responsibilities. The Schedules That Work Act would establish national fair scheduling standards, allow workers to make schedule requests, and require that employees receive their work schedules two weeks in advance, which could help them anticipate their child care needs.66

Conclusion

There is a strong link between child care access and mothers’ ability to work, yet a lack of public investment in child care means that families struggle to find the high-quality, affordable child care options that they need each day. Working families and families of color disproportionately face barriers to accessing child care, and their economic security is suffering as a result. It is long past time to implement policies that reflect and support the United States’ modern—and largely female—workforce.67

Enacting policies that increase access to child care is crucial to sustaining and strengthening the nation’s current and future workforce. Greater access to high-quality child care and early learning programs will support mothers so they can work and will benefit children, leaving them better prepared for kindergarten and to be productive citizens when they grow up. Child care must be central to any policy effort to promote gender equity, grow the nation’s workforce, and bolster the economy.

About the author

Leila Schochet is the policy analyst for Early Childhood Policy at the Center for American Progress.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Heidi Schultheis, Diana Boesch, and the Early Childhood Policy team for their input and review of this report.

Appendix

About the data sources

This report presents findings from the author’s analysis of the 2016 Early Childhood Program Participation Survey (ECPP), as well as results from a national child care poll conducted by the Center for American Progress in summer 2018.

Early Childhood Program Participation Survey

The ECPP was administered as part of the 2016 National Household Education Surveys Program (NHES:2016) and collected data specifically about children who had not yet started kindergarten.68 The ECPP includes data from 5,837 households and is a nationally representative survey, representing 21.4 million children from birth to age 5. The survey asks parents to respond to questions about their child, their child’s participation in early childhood education programs, and characteristics of their child’s household and family members. Parents report on only one child for the survey, even if there are other children in their home.

The CAP analysis of the survey data focused on the 60 percent of households that reported that they looked for child care in the past year. The analysis examined several key questions about these families’ experiences in their child care search. In addition to household demographic data, the report refers to the following questions throughout:

- “What is the main reason your household wanted a care program for this child in the past year?”

- “How much difficulty did you have finding the type of child care or early childhood program you wanted for this child?” For this analysis, the author defines “difficulty” as families who reported having “a little difficulty,” “some difficulty,” or “a lot of difficulty,” and defines families who did not find child care as those who said they “did not find the child care program I wanted.”

- “What was the primary reason for the difficulty finding care?”

Center for American Progress National Child Care Survey 2018

Later in this report, the author examines data from a survey conducted by CAP and GBA Strategies from June 18 to 26, 2018.69 The survey captured responses from 1,657 registered voters nationally and used an online panel and voter registration lists. The survey also included a subsample of 484 parents whose children were under age 18, as well as oversamples of African American and Hispanic women to allow for more detailed comparative analysis. The survey was weighted to reflect available national demographic data on registered voters.

This report refers to results from two specific questions asked in the survey:

- “Have you or a member of your immediate family had your career or career prospects negatively impacted—such as passing up a job or promotion, working fewer hours, or not being able to pursue new skills—due to child care considerations?”

- “If you had access to more reliable and affordable child care, would you or your child’s other parent take any of the following steps in relation to employment and work?”

- “Look for a higher paying job”

- “Ask for more hours at work”

- “Seek a promotion or more responsibility at work”

- “Seek additional education or training for your career”

- “Look for a different job that interests you more”

- “If currently not working, look for a job in the first place”

- “None of the above”

Methodology and key assumptions in the ECPP

Difficulty finding child care: The author analyzed responses from families that reported looking for child care in the past year—which accounted for about 60 percent of households in the ECPP survey. The author conducted descriptive analyses to report how much difficulty these families had finding child care, and examined various subgroups, for example, by household income, mother’s race and ethnicity, and child’s age. The author also examined the primary reason for difficulty finding child care among these subgroups; for this final portion of the analysis, the author did not report results for American Indian or Alaska Native mothers and for Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander mothers due to small sample size.

Employment: The original ECPP data set provides child-level data. Before analyzing the impact of child care access on parental employment, the author reshaped the data set to access individual-level data for each parent. This made it possible to evaluate employment and other characteristics among mothers and fathers.

For this analysis, the author decided to examine parental employment among families who reported looking for child care and who said that their primary reason for wanting a child care program was so that a parent could work or go to school. Although having access to child care enables many parents to work—including those who stated a different primary reason for seeking care—this assumption helped isolate the parents who explicitly stated that they were motivated to find child care so that they could work. The employment rate of parents in this analysis is higher than the national rate, perhaps because this was a subgroup of parents who were highly motivated to work.

The author compared employment among parents who reported “not finding the child care program [they] wanted” with all other families who reported looking for child care. Here, the author assumed that families who reported other degrees of difficulty ultimately found a child care program and therefore included them in the comparison group of families who found child care. The author defined “employed” as parents who reported that they are “employed for pay or income,” “self-employed,” or a “full-time student”; she defined “unemployed” as parents who reported that they are “unemployed or out of work” or “stay at home parents.” The author excluded parents who reported that they were “retired” or “disabled or unable to work” for the purpose of this analysis.