On February 27 the U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments in the case Shelby County v. Holder, a challenge to the constitutionality of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This landmark law outlawed discriminatory voting practices by ending the disfranchisement of minority voters and preventing vote dilution through racial gerrymandering and other techniques that negate the minority vote when the white majority votes as a block.

Section 5 furthers these goals by requiring nine full states and parts of seven other states with a history of racial discrimination in voting to ask either the Department of Justice or a three-judge court in Washington, D.C., for approval before making any changes to voting laws—a process known as preclearance. Congress determined the jurisdictions originally covered under Section 5 by using a plan laid out in the Voting Rights Act and also created a scheme for states to “bail out” of coverage if they have complied with the Voting Rights Act for 10 years. (see Figure 1)

Here are five reasons why Section 5, by protecting the right to vote, actually enhances our democracy and is good for all Americans.

1. Section 5 blocks discriminatory voting practices

Section 5 has blocked discriminatory state laws that would have disenfranchised or diluted the minority vote. Without Section 5:

- Texas would have passed the strictest voter ID law in the nation in 2011, placing unforgiving burdens on minority voters. The law would have allowed concealed handgun licenses to serve as a form of valid identification to vote, but would have rejected the use of a college ID or a state employee ID. Luckily, Section 5 blocked the law and saved African American and Latino voters from being disenfranchised in the 2012 election.

- Mississippi would have required people to register to vote twice: once for federal elections and once for state and local elections. Knowing that it is more difficult for minorities to overcome administrative barriers, this tactic would have resulted in diluting the minority vote in state and local elections. The Department of Justice, using Section 5, blocked the law in 1997.

- Georgia would have continued to use a voter verification program to check the citizenship status of every person seeking to register to vote. Because Georgia failed to receive Section 5 preclearance before implementing the law, evidence was obtained that made it clear that minority voters were being flagged at higher rates, requiring time-consuming additional steps to be taken to prove their citizenship. The Department of Justice denied preclearance for this law in 2009.

- Arizona would have implemented a redistricting plan that would have divided certain election districts so Latinos would no longer be the majority in those districts and would no longer be able to elect candidates of their choice to represent them. The Department of Justice denied preclearance for this law in 2002.

2. Section 5 safeguards local elections

The elimination of Section 5 may have the most devastating consequences in small cities and communities where individuals are less likely to litigate discriminatory changes. Section 5 requires covered jurisdictions to submit requests for even minor changes at the local level and protects against discriminatory practices that would otherwise go unnoticed.

- In 2011 the Pitt County School District in North Carolina decided to reduce the number of school board members from 12 to 7 and shorten their terms in office. Section 5 blocked the change from going into effect after the Department of Justice determined that such a change would decrease representation of minority-preferred candidates on the school board.

- In Clinton, Mississippi, where 34 percent of the population is African American, the city proposed to its six-member council a redistricting plan that did not include a single ward where African American voters had the power to elect candidates of their choice. Racially polarized voting is still a problem in Mississippi, and the redistricting plan ensured there was no longer a majority African American ward. The Department of Justice found reliable evidence that the city had acted with a racially discriminatory purpose and blocked the change from going into effect in 2011.

3. Section 5 prevents discrimination where race is still a barrier

Under the Voting Rights Act, jurisdictions that must seek preclearance have a history of racial discrimination in voting practices, and there is still evidence that racial discrimination is prevalent in Section 5-covered jurisdictions. Most of the states fully covered under Section 5 have the highest African American populations in the country, which should mean that African Americans are strongly represented in the government. But that is unfortunately not the case.

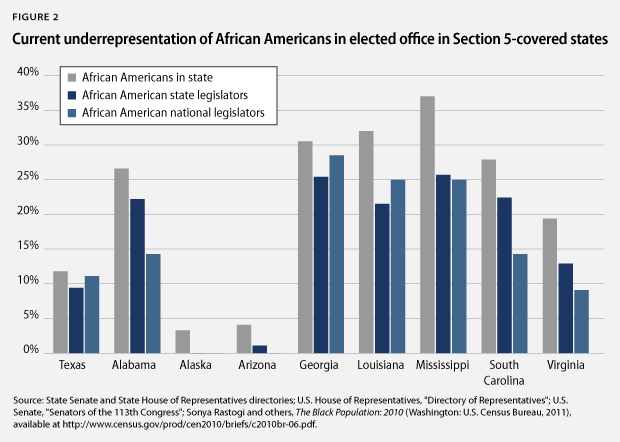

African Americans are still significantly underrepresented in state legislatures, in Congress, and in statewide offices such as governor and U.S. Senate positions. Where African Americans do serve in public office, they are elected in districts that are majority minority voters. Racially polarized voting such as this indicates that race is still a factor in how people vote. (see Figure 2 on following page)

- Mississippi, which is nearly 40 percent African American—the highest population of African Americans in any state in the country—has never elected an African American governor. There is one African American currently in Congress who represents Jackson, Mississippi, which is more than 60 percent African American.

- Louisiana, Mississippi, Virginia, Georgia, and South Carolina lead the country in being the most underrepresented when it comes to African Americans in the state legislature.

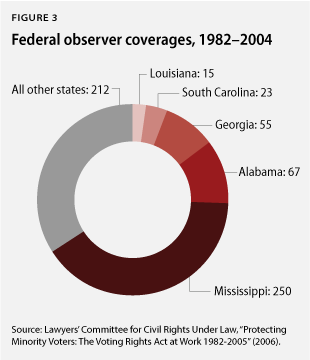

In addition, federal observers are frequently sent to Section 5-covered states on Election Day. The U.S. attorney general is permitted to send federal observers to certain Section 5-covered jurisdictions if there is reason to believe that voting rights will not be protected. Between 1966 and 2004, the attorney general sent a total of 1,142 federal observers to different states to monitor voting practices during elections. Most of these observers are sent into counties that are more than 40 percent nonwhite. Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina accounted for 66 percent of all federal observer coverages between 1982 and 2004. When federal observers are sent to a jurisdiction, it is referred to as an “observer coverage.” (see Figure 3) In the 2012 presidential election, the Department of Justice sent observers into counties in all of the fully covered Section 5 states except Virginia.

4. Section 5 is a necessary alternative to costly, time-intensive litigation

Congress passed the Voting Rights Act because case-by-case litigation was not working to protect the right to vote in states where racial and ethnic discrimination mostly occurred. It was slow, difficult, and costly to challenge every type of voter suppression tactic used in counties and states around the country. And even when litigation was successful in stopping the unconstitutional practices, state officials would ignore the court orders or find some new discriminatory scheme to ensure minorities could not exercise their right to vote.

This would not be any different today. Consider the number of states that passed voter suppression laws since 2010 in Section 5-covered jurisdictions. Without Section 5, minority voters would have had to build a case, front the costs, and challenge the following laws:

- Proof-of-citizenship laws: Alabama, Arizona, and Georgia

- Voter ID laws: Alabama, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas—in fact, because of Section 5, South Carolina watered down its original version of the law before seeking approval from the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia

- Limits to early voting: Georgia

- Instead, Section 5 required the Justice Department or the D.C. Circuit Court to approve the laws before they disenfranchised minority voters.

5. Section 5 has moved our country forward

Thanks to the Voting Rights Act and Section 5, the United States has made immense progress in protecting and expanding the right to vote. In Section 5-covered jurisdictions, change is happening, although slowly, but it may not have happened at all if it were not for the Voting Rights Act and Section 5. The changes we see include:

- The election of the first African American president

- A higher percentage of African American elected officials—the number of which has increased from just 300 nationwide in 1964 to more than 9,100 today

- The highest-ever percentage of African Americans in Mississippi’s state legislature—27 percent—since the first African American to Mississippi’s state legislature was elected in 1967, following the passage of the Voting Rights Act

- A more diverse electorate

Racial discrimination continues to be a problem in our country, particularly in Section 5-covered states. Section 5 serves as a shield to protect minority voters in jurisdictions where progress has come slowly and continues to be a necessary remedy to disenfranchisement. Without it, minority voters would be in jeopardy—and so too would our democracy.

Sandhya Bathija is a Campaign Manager with Legal Progress at the Center for American Progress. Jacqueline Odum, an intern with Legal Progress, also contributed to this report.