When House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R-WI) introduced his latest budget resolution, it predictably included harsh cuts to the vital programs for poor and middle-class Americans that are at the core of the progressive agenda.

But the House Republican budget is not just contrary to progressive values; it is also the wrong approach for our economic reality. Some of its economic flaws in logic are fundamental and basic; for example, the House Republican budget includes misunderstandings about supply and demand, focusing on the supply side of the economy despite the fact that our current economic problems are rooted in a lack of demand. It also ignores decades of empirical evidence on the effects of upper-income tax rates on economic growth and inequality.

Other policy mistakes are more subtle, but no less damaging. Ryan’s budget redistributes income upward, increasing drag on our slow recovery. It also proposes the block granting of assistance programs, making future recessions more severe.

There is nothing new here. Rep. Ryan’s budgets have all been disappointingly similar and lack a balanced approach to address our country’s economic challenges. And given the track record of this agenda, it is not just everyday Americans but also the broader U.S. economy that would suffer if the House Republican budget were ever enacted into law.

Supply and demand

As he did when there were 15.2 million, 13.7 million, 12.7 million, and 11.7 million Americans unsuccessfully trying to find jobs, Rep. Ryan looked at the 10.5 million Americans who were actively looking for work in February 2014 and somehow found a lack of labor supply. Economists have not been in greater agreement about the challenges the economy faces in at least a generation: The country has a shortfall in aggregate demand and has since Rep. Ryan started proposing budgets. The harsh austerity measures in each Ryan budget are sold as the way to get America moving, even though this is the exact opposite of what textbook economics calls for to address a demand shortfall. Unsurprisingly, the Congressional Budget Office, or CBO, projects that this latest budget will actually shrink the economy for the next three years.

Some economists have described the behavior of the U.S. economy over the past decade as a “secular stagnation,” meaning that we have had a shortfall of aggregate demand that is not cyclical—as is typical in a recession. Instead, this shortfall is a longer-term problem that could become a new normal if not properly addressed. The solution to this problem is to raise aggregate demand, which we can do in three ways: looser monetary policy, by running higher deficits to fund tax cuts, or by increasing government spending. Higher short-term deficits would be important for both the tax cut and government spending options in order to inject new resources into the economy. Loose monetary policy is problematic as a long-run policy both because interest rates are already basically zero and because lower interest rates encourage leverage, raising the risk of asset bubbles. Tax cuts might be effective if they were targeted at low-income households, which are most likely to spend the money and boost aggregate demand. Since households are still deleveraging after the financial crisis, however, it is likely that individuals at all income levels would use most of this money to reduce their debt levels, which has little effect on demand.

Economists grappling with secular stagnation, including Larry Summers, Brad DeLong, and Lawrence Ball, have advocated for public investment as the most cost-effective way to raise long-term aggregate demand to deal with this shortfall. Boosting government spending on public investments could pose problems if we were already chronically overinvesting in public infrastructure, but there is little reason to believe this is the case. Since government investment has fallen as a share of gross domestic product, or GDP, from its historical average over the past several decades, there is more than enough room to make new public investments without crowding out private investment.

Making today’s economic problems worse—as this Ryan budget again does with misguided austerity—has long-term economic and fiscal consequences. As we have seen in Europe, using austerity to balance budgets is often self-defeating; a government takes money out of the economy to balance its budget, causing the economy to contract and resulting in larger future deficits as tax revenues fall with GDP. CBO highlighted this problem in its most recent budget outlook:

Persistently weak conditions in the labor market have led some workers to permanently leave the labor force, and the lasting effects of high long-term unemployment have boosted the natural rate of unemployment relative to its prerecession level. In addition, the low level of investment during the past several years has held down the growth of capital services, and, despite CBO’s projection of brisk growth in investment in coming years, the agency does not expect the capital stock in 2024 to be as large as it would have been in the absence of the recession. Also, CBO estimates that the protracted weakness in demand and large amount of slack in the labor market have lowered potential total factor productivity (the average real output per unit of combined labor and capital services) by reducing the speed with which resources are being reallocated to their most productive uses, slowing the rate at which workers are gaining new skills, and restraining businesses’ spending for research and development.

CBO’s revisions to its economic forecast have increased its deficit projections by more than $1 trillion over the next 10 years. This extra $1 trillion in deficits does not occur because the government is spending more or taxing less: By embracing austerity at the wrong time, Congress has permanently shrunk the size of the U.S. economy, making our deficit situation worse under any budget plan.

Giving away the future to hit an arbitrary number

A large portion of public investment is funded by the nondefense discretionary budget. But instead of making new investments, the House Republican budget cuts nondefense discretionary spending below even the economically destructive levels imposed by sequestration. It did the same thing last year, but even House Republicans ultimately rejected those unrealistic cuts when they failed to write detailed spending bills to implement their own budget. While Rep. Ryan seems to have taken no policy lessons from this failure, he does seem to have learned one important political lesson: This year, his budget does not require any new cuts for fiscal year 2015—the only year for which this Congress has to write detailed spending bills.

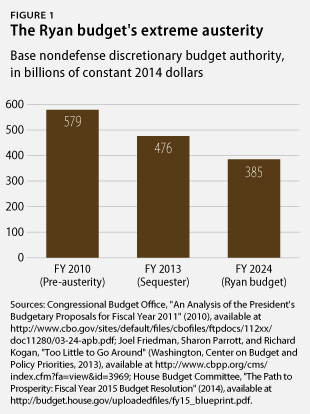

Starting in FY 2016, the budget returns to the deep, abstract cuts to nondefense discretionary spending it could not make add up last year. Over 10 years, it cuts nondefense discretionary programs by $791 billion. By 2024, the final year for which the budget provides spending caps, it cuts nondefense discretionary spending to a level that is 19 percent lower than even the sequester levels from FY 2013, once inflation is taken into account. The Ryan budget’s FY 2024 nondefense discretionary levels are 34 percent lower than the pre-austerity level from FY 2010.

The 2013 sequester cuts threw more than 57,000 children out of Head Start preschools, stalled scientific research, and eliminated hundreds of thousands of jobs. The effects would have been even worse if Congress had allowed sequestration to continue unabated. CBO estimated that sequestration would have reduced GDP by 0.6 percent and eliminated 800,000 jobs by the end of 2014. But even sequestration would be a far better economic policy than this House Republican budget.

Nondefense discretionary spending is already projected to fall to historically low levels under current law—even if the sequester is fully repealed—but that is not enough for Rep. Ryan. The House Republican budget’s massive cuts will mean less money for sectors such as education, infrastructure, science, veterans’ health, safety net programs, and job training. Cutting the part of the budget that funds job training is particularly odd for Rep. Ryan, given his previous statements on job training and poverty. When Fox News host Bill O’Reilly recently asked Rep. Ryan to suggest “one very vital thing that the federal government can do, specifically not philosophically, to alleviate poverty,” Rep. Ryan answered, “Well, job training and skills, that’s a big deal.” But instead of investing in job training and skills, the House Republican budget just keeps cutting from nondefense discretionary spending, which is the funding source for these programs.

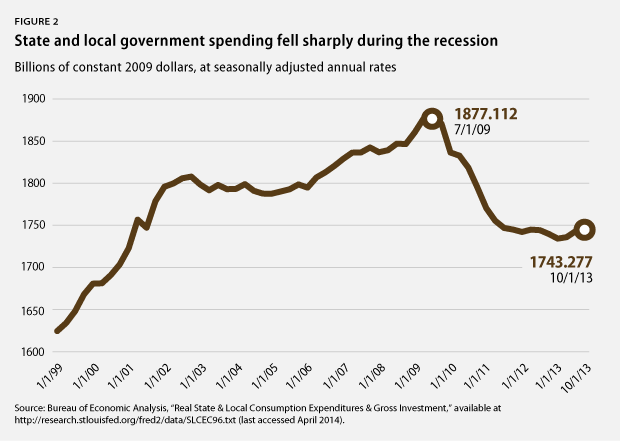

The economic problems caused by the House Republican budget cuts go beyond nondefense discretionary spending. Converting federal programs into block grants, as the House Republican budget does for Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, formerly known as food stamps, means that federal support for those programs remains fixed, regardless of changes in economic conditions or human need. When the economy is struggling, only the federal government has the fiscal flexibility to run deficits to cushion the blow, as balanced budget rules in state and local governments force those governments to cut back during recessions.

Rep. Ryan’s budget would compound this state and local budget problem by block granting federal programs; this would have the likely effect of amplifying recessions, a flaw that escapes his mention, though it has worried policy wonks since the 1990s. Currently, programs such as SNAP expand automatically during recessions, softening the blow to the economy as a whole. When need drops during good economic times, the federal government spends less. Economists call these programs automatic fiscal stabilizers, and they have made the U.S. economy much more stable over time. Converting federal programs into block grants means these programs would no longer act as automatic stabilizers, and any increased need for funding cannot be met by the federal government until politicians agree to fix the economy. As we have unfortunately learned over the past several years, relying on Congress for timely economic action is a poor strategy.

Trickle down versus middle out

Just like earlier House Republican budgets, this year’s budget makes reducing the top tax rate a centerpiece of its economic agenda. This delivers an enormous windfall to the wealthiest Americans, whose tax rate would fall from 39.6 percent to 25 percent. In addition to the top 1 percent, corporations are also big winners. Rep. Ryan proposes cutting the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 25 percent. An analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy finds that the average millionaire would get a six-figure tax cut from the Ryan budget.

Lowering top tax rates has long been a bedrock principle of conservative economic orthodoxy. We have been talking about Republican supply-side tax cuts for so long that the term has lost some meaning, but the concept is rooted in two incentive effects. First, lower top tax rates give the wealthy more money, which enables them to work less and maintain the same standard of living, reducing their incentive to work. Second, lower top tax rates mean the wealthy get to keep more of every dollar they earn, which makes work more lucrative and increases their incentive to work. If the second effect dominates, then lower tax rates increase aggregate supply. If the first effect dominates, then they lower aggregate supply. If the two effects cancel out, then reducing top tax rates has no meaningful effect on overall economic output.

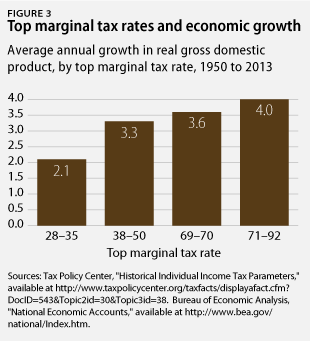

The data show that low top tax rates have actually coincided with periods of relatively weak economic growth in the United States over the past 60 years. That does not necessarily mean that low top tax rates cause poor economic growth—correlation does not prove causation—but it certainly undermines the conservative dogma at the foundation of the House Republican budget.

A 2012 paper by Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez also found that cutting top marginal tax rates has not led to economic growth, but that it does seem to help the rich get richer. In other words, nothing trickles down. Piketty and Saez analyzed 18 countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, and found no correlation between changes in their top tax rates and economic growth. But there was a strong correlation between lower top tax rates and higher levels of income inequality. The United States and United Kingdom reduced their top tax rates over the past 50 years more than any of the countries analyzed, and the share of their national income flowing to the top 1 percent increased the most.

The growing concentration of income and wealth at the top is often discussed in moral terms, but it also has significant economic implications. While many people find the image of a rich person buying lavish yachts distasteful, it is better for the economy than what usually happens—nothing. Rich people spend much less of their money than the rest of us. You can only have so many yachts, and with inheritance taxes at historic lows, how responsible is it to spend your children’s fortune? What this means for the economy is that at any level of GDP, higher income inequality reduces demand for goods and services.

While we hear a lot about the role of wealthy job creators, their role in driving American investment has declined dramatically as global capital markets have become more integrated—another reason the supply-side solutions from the 1980s are out of date. In terms of increasing aggregate demand, the middle class, and especially younger individuals, are key drivers of the economy. Simply put, middle-class families spend more of what they take home on the goods and services that create aggregate demand and jobs.

By focusing its economic strategy on the wealthy and corporations, the House Republican budget leaves the poor, the middle class, and the broader economy behind. The House Republican budget claims that “tax reform” will pay for the huge tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations, but it does not name a single loophole to close. A Tax Policy Center analysis of an identical tax plan in last year’s House Republican budget found that its tax cuts would cost about $5.7 trillion over 10 years. At the time, the Center for American Progress called it a “fantasy budget,” in part because there was no way to make the numbers add up, at least without an enormous middle-class tax increase. The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy found that even if tax reform took away every itemized deduction and tax credit claimed by the wealthy and made them pay taxes on their employer-provided health care, the House Republican budget would still give millionaires an average tax cut of at least $200,000. Someone else would have to pay the bill.

Since last year’s House Republican budget, House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI) introduced a tax reform bill that at least tries to confront the reality of tax reform. In light of that reality, Rep. Camp abandoned the 25 percent top individual tax rate and only cut the top rate to 35 percent. But this year’s House Republican budget is written as if no lessons were learned from Rep. Camp’s experience. It specifies that the goal of its tax reform plan is a top individual and corporate tax rate of 25 percent, and it specifies that total tax collections will not fall relative to current law. It is clearer than ever before that these criteria can only be satisfied by raising the taxes of poor and middle-class Americans.

In addition to raising their taxes, the House Republican budget targets the health care of low- and middle-income Americans for especially large cuts. It transforms Medicare into a voucher program, which it calls “premium support” because the voucher is supposed to pay for health insurance premiums for either traditional Medicare or private insurance. CBO estimated that premiums for traditional Medicare would increase by 50 percent under this plan, making it unaffordable for many seniors and forcing them into the private insurance market.

While traditional Medicare would become a luxury that only wealthy seniors could afford, Medicaid beneficiaries would fare even worse. The House Republican budget cuts Medicaid by about $1.5 trillion in the first 10 years by repealing the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion and sharply cutting what would be left of Medicaid. Cuts to Medicaid—a program devoted to providing health care to low-income Americans—constitute about one-third of the House Republican budget’s $4.8 trillion in cuts to nondefense programs, not including interest savings. This is not the waste, fraud, and abuse that some conservatives focus on when discussing budget cuts; taking away Medicaid coverage would force families into bankruptcy for having a child who needs a lifesaving medical intervention or a loved one who needs nursing home care.

Excess growth in health care costs is one of the key drivers of our long-term debt, but Medicaid is not the problem. Since 1975, Medicaid has consistently had the lowest rate of excess growth in health care costs among federal health programs. From 1990 to 2011, Medicaid had barely any excess cost growth, with its health care costs growing only 0.2 percent faster than GDP, while overall health care costs grew 1.2 percent faster than GDP over the same time period. Over the long term, CBO projects that under current law excess cost growth in Medicaid will eventually fall to zero.

The House Republican budget also repeals the assistance provided by the Affordable Care Act for low- and middle-income households to buy private insurance. Those subsidies have already helped millions of Americans get coverage. CBO projects that by 2016, 22 million Americans will have private health insurance purchased on the exchanges created by the Affordable Care Act, and 12 million more will have coverage through the Medicaid expansion. The House Republican budget would take away their health insurance.

The budget’s cuts to Medicaid and Affordable Care Act insurance subsidies total about $2.7 trillion over 10 years. This means that more than half of the Ryan budget’s noninterest program cuts are focused entirely on reducing assistance for low- and middle-income Americans trying to get health insurance. This does not even count the Medicare cuts, most of which occur after the first 10 years. It also does not include the cuts to nutrition assistance, disability payments, Pell Grants, or anything else in the House Republican budget. All told, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that 69 percent of the House Republican program cuts come from programs that serve Americans with low and moderate incomes.

These cuts are not pragmatic. Only with a fervent commitment to trickle-down ideology can it possibly make sense to cut all these programs for and raise the taxes of low- and middle-income Americans while giving the wealthy and corporations tax cuts. The House Republican budget not only favors the wealthy, but it also does so at the expense of the economy as a whole.

Conclusion

Like the earlier budgets written by Rep. Ryan, this one is not likely to be taken seriously by anyone but House Republicans, nor should it be. It relies on outdated economic theories that would be wrong for our economy’s actual problems even if they were not discredited. But this year’s House Republican budget still serves one useful purpose: It makes clear to the American people that they have important choices to make about which path to choose for our economic future. If we choose the path advocated by Rep. Ryan, then the House Republican budget becomes a serious governing document to tilt the economic playing field even further toward the wealthy and away from everyone else.

Harry Stein is the Associate Director for Fiscal Policy at the Center for American Progress. Michael Madowitz is an Economist at the Center.