Introduction and summary

The national conversation about gun violence in the United States focuses primarily on the harms caused by the misuse of firearms—the details of the incidents that take the lives of 40,000 people every year and grievously injure tens of thousands more.1 This debate often occurs in the aftermath of specific gun-related tragedies and tends to focus on the individual who pulled the trigger and what could have been done to intervene with that person to prevent the tragedy.

But largely absent from the national conversation about gun violence is any mention of the industry responsible for putting guns into our communities in the first place.

The gun industry in the United States is effectively unregulated. The laws governing the operation of these businesses are porous and weak. The federal agency charged with oversight of the industry—the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF)—has been historically underfunded and politically vulnerable, making it nearly impossible for the agency to conduct consistent, effective regulatory oversight activities. Adding insult to injury, Congress has also imposed restrictions on how ATF can perform this regulatory work through restrictive policy riders on the agency’s budget. Congress has also eliminated some of the most useful tools for ensuring that gun industry actors operate their businesses in the best interests of consumers and are held accountable for harm caused by their products.

The result of this constellation of weak laws, lack of resources, and dearth of political will to support gun industry regulation is that the industry that produces and sells deadly weapons to civilian consumers has operated for decades with minimal oversight from the federal government and almost no accountability in the U.S. legal system.

This is not an idle concern. The United States experiences rates of gun violence that no other high-income nation comes even close to matching.2 This violence persists, even as the number of Americans who choose to own guns has steadily declined.3

Efforts to reduce gun violence that focus solely on the demand side of the problem ignore the role of the gun industry—manufacturers, importers, wholesalers, and retail gun dealers—in manufacturing and distributing the guns that are the instruments of this violence. These supply-side actors make decisions that directly affect the kinds of guns and ammunition that are manufactured and sold, the safety features included on those guns, the commercial channels in which they are sold, and the safeguards in place at the point of sale to prevent gun trafficking and theft.

A crucial component of a comprehensive plan for reducing gun violence in the United States is robust regulation and oversight of the gun industry. It is not enough to simply focus on the individuals who use guns to commit acts of violence—an approach that has contributed to overcriminalization and targeting of communities of color as part of a “tough on crime” approach to criminal justice.4 To truly address all aspects of the gun violence epidemic in this country, policymakers must focus on the role the gun industry plays in enabling and exacerbating this violence.

This report discusses the gaps in the current law regarding gun industry regulation and oversight. It then offers a series of policy solutions to address these gaps, including:

- Increasing oversight of gun manufacturers, importers, exporters, and dealers

- Requiring licensed gun dealers to implement security measures to prevent theft

- Strengthening the National Firearms Act review and determination process

- Strengthening oversight of homemade guns, ammunition, and silencers

- Giving the Consumer Product Safety Commission authority to regulate guns and ammunition for safety

- Repealing the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act

The high rates of gun death experienced in this country are not inevitable or, as some in the gun lobby claim, “the price of freedom.”5 There is much more that can be done to provide better oversight and regulation of the gun industry, which would have a significant impact on reducing gun violence and making all of our communities safer.

Overview of the U.S. gun industry: Manufacturing, importation, exportation, and commercial sales

Throughout the history of the United States, laws to regulate the firearm industry have lagged behind the growth and innovation of that industry. The first major federal law in the United States regulating guns was not enacted until 1934—despite the presence of a robust industry in firearms in this country for more than a century prior.6 This law, the National Firearms Act (NFA), was a relatively narrow measure primarily designed as a response to a dramatic increase in organized violent crime during the Prohibition era, particularly the use of machine guns.7 The law didn’t change again until 1968, when the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr., President John F. Kennedy Jr., and Robert Kennedy served as the catalyst for a major piece of legislation, the Gun Control Act of 1968.8 This new law for the first time established a framework for the lawful commerce in firearms that included a system of federal regulatory oversight of gun and ammunition manufacturers, importers, and dealers that required these businesses to become licensed by the federal government and subject themselves to oversight in the form of inspections and mandatory record keeping.9

The federal law governing the operation of the gun industry changed again in 1986, although this change was designed to loosen regulation of the industry. The Firearm Owners’ Protection Act (FOPA) amended the Gun Control Act in a number of ways that weakened oversight of the industry, including by limiting the number of compliance inspections ATF can perform on gun dealers, raising the legal standard for penalizing dealers for violations, and creating a substantial exception to the requirement that vendors of guns obtain a license from ATF for those who conduct only “occasional” sales. FOPA also significantly reduced regulation of ammunition by eliminating the requirement that businesses seeking to sell ammunition obtain a license from ATF or retain any records related to ammunition sales.10

The most recent major federal legislation affecting the gun industry was the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, which was finally enacted in 1993 despite being motivated by the attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan in 1981 in an incident that ultimately led to the death of his press secretary, James Brady. The Brady Act created the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) and enacted a new requirement that licensed gun dealers conduct a background check before completing a sale to ensure that any prospective buyer is not statutorily prohibited from gun possession.11 In addition, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 included a provision banning assault weapons; however, this provision was allowed to sunset in 2004 and the industry was once again able to manufacture and sell these types of firearms.12

There has been no significant change to the federal law governing commerce in firearms in more than 20 years. The law has failed to keep up with changes in the industry, in terms of scope, size, and the type of products being designed and sold. The laws are woefully out of date and unprepared to address advances in technology such as internet gun sales, 3D printing, homemade and untraceable ghost guns, and a proliferation of firearm silencers and other dangerous accessories. In addition, the law continues to tie the hands of the federal agency charged with conducting regulatory oversight of the industry.

Gun manufacturing

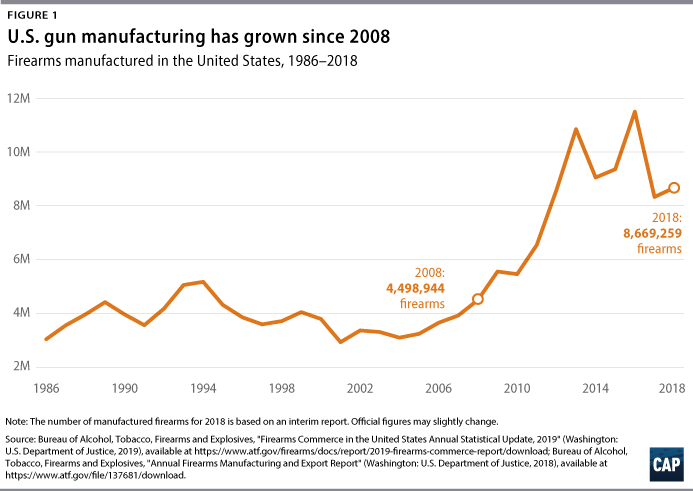

The United States has been home to a robust firearms industry for decades. The earliest available data provided by ATF on firearms manufacturing reveals that 3.04 million guns were manufactured in the United States in 1986.13 While this volume of gun manufacturing remained relatively stable in the 1990s and 2000s, ATF data reveal a significant increase in recent years. While an annual average of 3.8 million firearms were manufactured in the United States from 1986 to 2008, this average more than doubled to an annual average of 8.4 million firearms per year from 2009 to 2018.14 (see Figure 1)

Gun manufacturing in the United States reached a 31-year high in 2016, with 11.5 million firearms manufactured. Gun production has dropped since then, decreasing 28 percent in 2017 and 25 percent in 2018.15 Even with these drops, however, 2017 and 2018 were the seventh- and fifth-highest years for firearm manufacturing, respectively.16

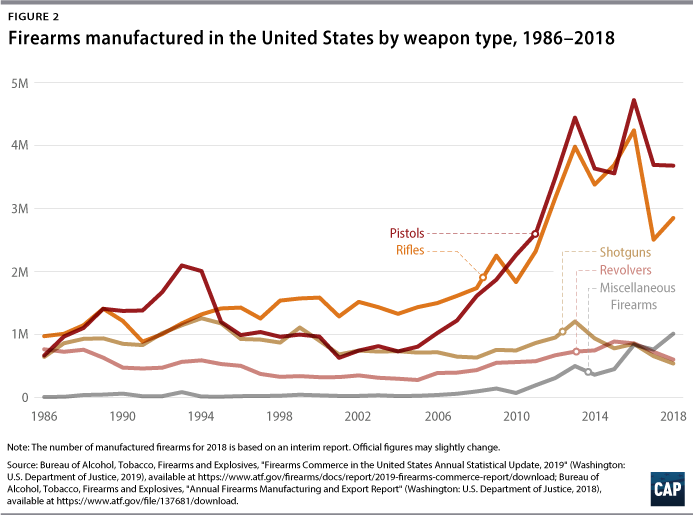

The rise in gun manufacturing in recent years is driven primarily by rifle and pistol production. (see Figure 2) According to ATF data, close to 76 percent of firearms manufactured from 2009 to 2018 were either pistols or rifles.17 Within the category of pistols, the rise in production is likely attributable, at least in part, to an increase in the manufacturing of large caliber concealable pistols.18 Additionally, the category of miscellaneous firearms, which includes items such as pistol grip firearms,19 firearm frames, and receivers, has grown considerably since 2010. While close to 851,000 miscellaneous firearms were manufactured from 1986 to 2009, more than 3.4 million were produced from 2010 to 2018.20

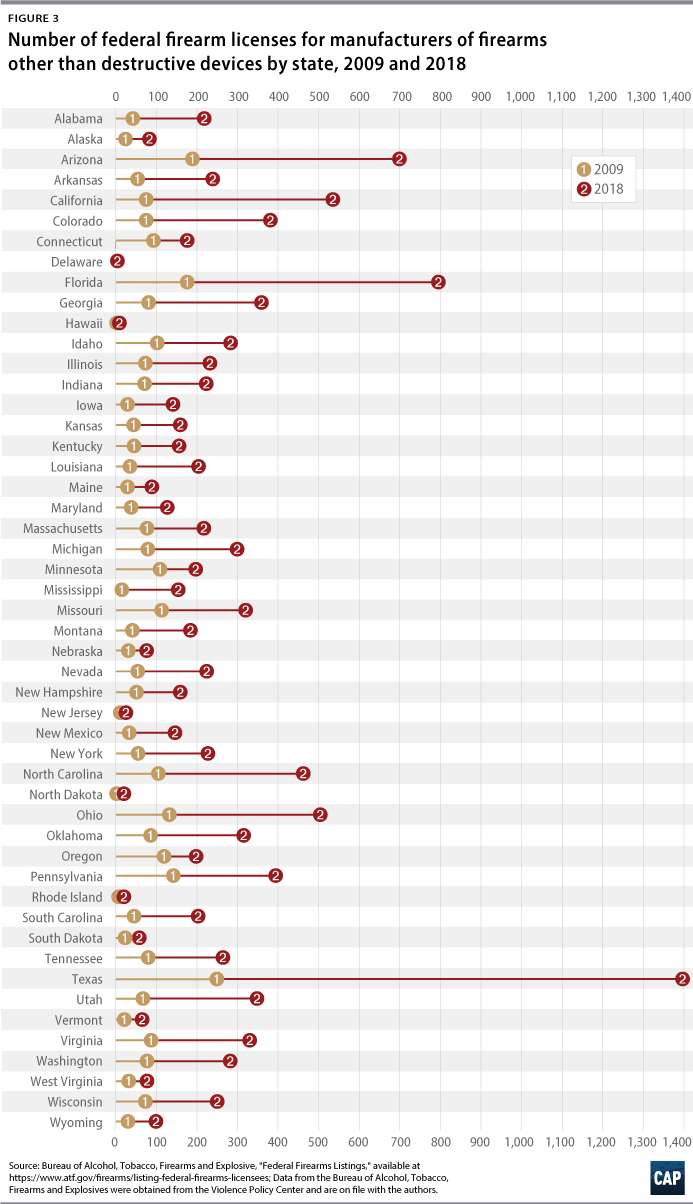

The dramatic growth in the gun manufacturing industry is also demonstrated by an increase in the number of licensed gun manufacturers in the country, which grew 255 percent from 2009 to 2018. As of 2018, there were nearly 12,600 licensed firearms manufacturers in the United States.21 The increase in the number of licensed gun manufacturers occurred nationwide, although there are significant differences in the size of the gun manufacturing industry from state to state. (see Figure 3)

While there are a significant number of gun manufacturers in the United States, total gun production is largely concentrated among a few large companies. Three manufacturers were responsible for producing more than 58 percent of pistols made from 2008 to 2018: Smith & Wesson Corp., Sturm, Ruger & Co. Inc., and SIG SAUER Inc.22 Similarly, three manufacturers were responsible for the production of more than 45 percent of rifles produced from 2008 to 2018: Remington Arms, Sturm, Ruger & Co. Inc., and Smith & Wesson.23

Licenses to manufacture ammunition have also increased, from 1,511 in 2009 to 2,119 in 2018.24 Currently, there is no reporting requirement for ammunition manufactured in the United States, so there is no way to have an accurate accounting of how much ammunition is manufactured in a given year.

There are relatively few barriers to entry in the gun manufacturing sector. To make firearms in the United States, an individual or business must obtain a firearms manufacturing license from ATF, known as a type 07 license. There are no substantive requirements to qualify as a gun manufacturer: Applicants must only be over age 21, be eligible to possess guns under federal law, and not have willfully violated any federal laws or regulations related to firearms.25 A three-year manufacturer’s license requires a $150 fee, and ATF is statutorily required to act on the license application within 60 days, regardless of how much scrutiny an individual application may warrant.26 Gun manufacturers must also register with the Directorate of Defense Trade Controls at the U.S. Department of State and pay an annual $2,250 fee to that agency.27

Gun manufacturers are currently subject to relatively little oversight by ATF upon receiving their license to operate. Manufacturers are required to maintain records of their firearm production and sales and are subject to one potential annual inspection of inventory and records to assess compliance with applicable laws and regulations.28 Manufacturers are also required to report the theft or loss of any firearms to ATF with 48 hours of discovery and to respond “immediately” to crime gun trace requests.29 In addition, licensed manufacturers are required to report to ATF annually on the production of firearms, even if a manufacturer did not produce any firearms during the reporting period.30 However, compliance with this requirement appears to be poor. In 2017, only 3,430 of the 11,946 licensed firearm manufacturer licensees reported to ATF on their production. This suggests two possibilities: that only 29 percent of licensees completed this requirement during 2017, meaning that the reported number of firearms manufactured in the United States that year could be an undercount, or that a significant number of licensed manufacturers paid their fees but did not produce any weapons.

Gun imports

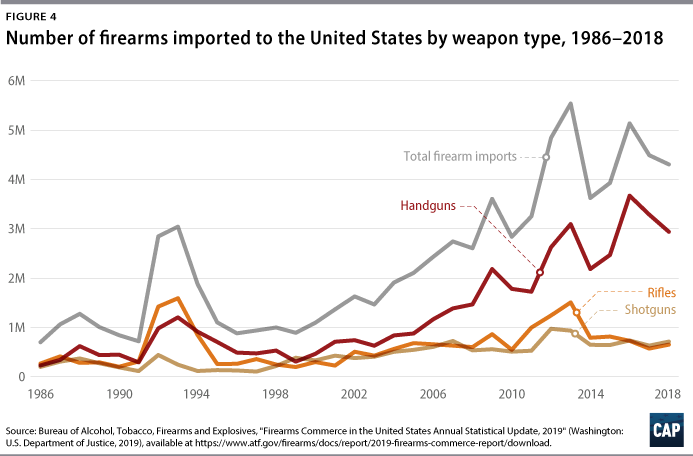

While the majority of new guns available for sale in the United States are manufactured domestically, a significant number of guns are imported into the country every year as well. Following similar trends as domestic manufacturing, gun imports have more than doubled in recent years: While the United States imported an annual average of 1.5 million firearms from 1986 to 2008, this annual average grew to 4.2 million firearms per year from 2008 to 2018.31 This increase was driven primarily by handgun and rifle imports.32 (see Figure 4)

Guns imported to the United States primarily originate from 15 countries.33 Austria is the top supplier of foreign-made guns, providing more than 5 million firearms, primarily handguns, to the U.S. market from 2013 to 2018. Brazil, Croatia, and Germany are other top suppliers of handguns, while Canada, Italy, and Turkey export a significant number of rifles and shotguns to the United States.34

Similar to firearm manufacturers, entities seeking to import guns must obtain a license from ATF, pay an annual fee of $50, and submit to a background check to ensure the key individuals are not prohibited from gun possession under federal law.35 Once granted, import licenses have a duration of three years.36 The number of these licenses has also increased considerably. While there were 735 entities holding a gun import license in 2009, this figure rose to 1,127 licensees in 2018, a 53 percent increase.37 Looking at data for 2018, more than 40 percent of these licenses were held by individuals or businesses in just six states: Florida, Texas, California, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Arizona.38

The duty to regulate firearms imports falls on both ATF and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). To import guns, individuals must fill out an ATF form that clearly identifies the type and number of firearms being imported in each individual shipment.39 Once the forms are approved by ATF and those firearms enter the United States, CBP officials examine the items to ensure that they match with what was approved by ATF.40 If everything is in order, CBP will approve those firearms to leave the port of entry and enter the United States.

In 1989, following a mass shooting at an elementary school in Stockton, California, that was perpetrated with a semiautomatic assault rifle and killed five children, President George H.W. Bush used executive authority to implement a ban on the importation of most models of foreign-made semiautomatic assault rifles.41 The ban applies to semiautomatic rifles that are determined by ATF as not “particularly suitable for or readily adaptable to sporting purposes,” which the agency defined in 1989 and reinforced in 1998 as those that have certain military-style features, such as “ability to accept a detachable magazine, folding/telescoping stocks, separate pistol grips, ability to accept a bayonet, flash suppressors, bipods, grenade launchers, and night sights.”42 However, in the late 2000s, members of Congress and gun violence prevention advocates began raising concerns that a combination of lax enforcement at ATF and innovation by foreign firearm manufacturers had led to an increase of foreign-made semiautomatic assault rifles being imported into the country despite the ban.43

In addition, industry lobbyists have sought to narrow the definition of unlawful “non-sporting” firearms in order to increase the scope of legally importable weapons.44 These efforts largely have failed, however, perhaps due in part to opposition by domestic gun manufacturers.45 As a result, the definition of a nonsporting rifle for import purposes has remained largely unchanged since the 1998 study; a more recent study reassessing sporting shotguns also failed to narrow the ban.46

Gun exports

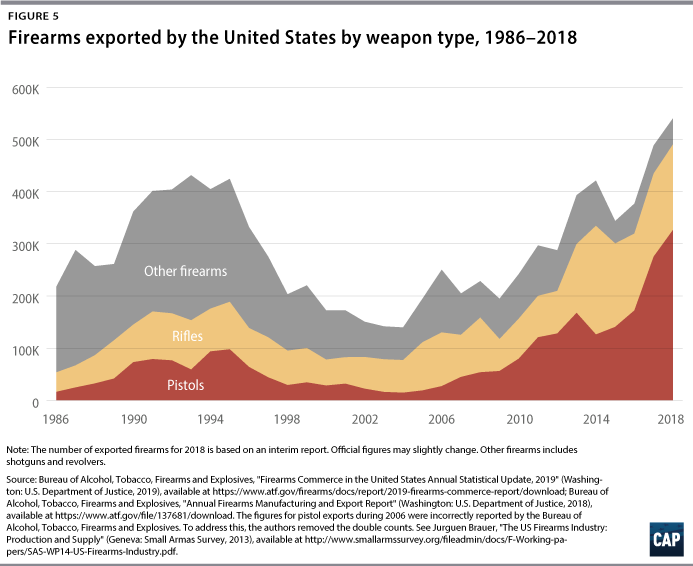

Not all guns manufactured in the United States are destined for the U.S. market—many are exported to foreign countries to both civilian and military purchasers. Gun exports have followed trends similar to those of domestic manufacturing and imports, rising sharply during the mid-2000s and continuing through 2018, the most recent year for which data are available. As shown in Figure 5, there has been a shift in the type of guns being exported: Prior to 1995, nearly 60 percent of exported firearms were revolvers and shotguns; however, from 2005 to 2018, rifle and pistol exports grew to make up the largest share of exported guns, accounting for more than 75 percent of the total.47

Data from the U.S. Census Bureau reveal the primary countries receiving exported firearms from the United States from 2014 through 2018, the most recent years for which data are available.48 Handguns were primarily exported to Thailand, Canada, the Philippines, and Belgium. Canada is by far the biggest recipient of U.S. long guns, with more than $350 million worth of imports from 2014 through 2018. In fact, Canada spends more money on the importation of U.S. long guns than the other top 30 countries combined.49

In January 2020, the Trump administration weakened oversight of small arms exports through a regulatory change that shifted export controls of semiautomatic pistols, assault-style firearms, certain sniper rifles, and their ammunition from the jurisdiction of the U.S. Department of State to the U.S. Department of Commerce.50 This has raised concerns in the international arms control community, as the Commerce Department uses less robust protocols for ensuring that exported goods are not sent to criminal organizations or human rights violators.51 Additionally, this rule removed congressional oversight of potential arms transfers, furthering concerns that these changes will lead to an increase in U.S. weapons being used in armed conflicts and human rights abuses around the world.52

Licensed gun dealers

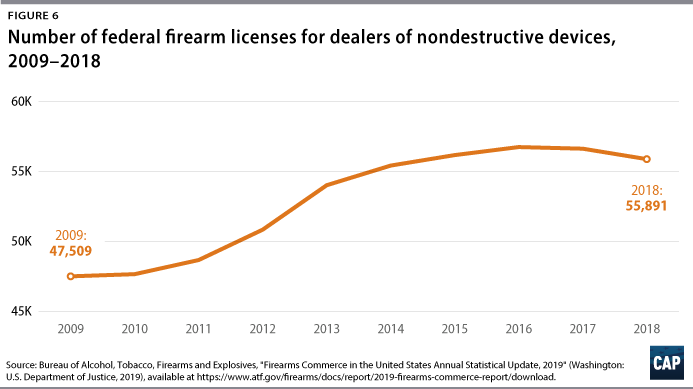

The exponential increase in the size of the U.S. gun industry is also evidenced by the increase in the number of individuals licensed to operate as gun dealers. While there were close to 47,500 licensed gun dealers in 2009, this figure rose to more than 55,900 by 2018, an 18 percent increase.53 (see Figure 6) During the same period, the U.S. population rose by only 6.6 percent,54 suggesting that the rise in the number of gun dealers is mainly driven by an increase in the size of the gun industry rather than population growth.

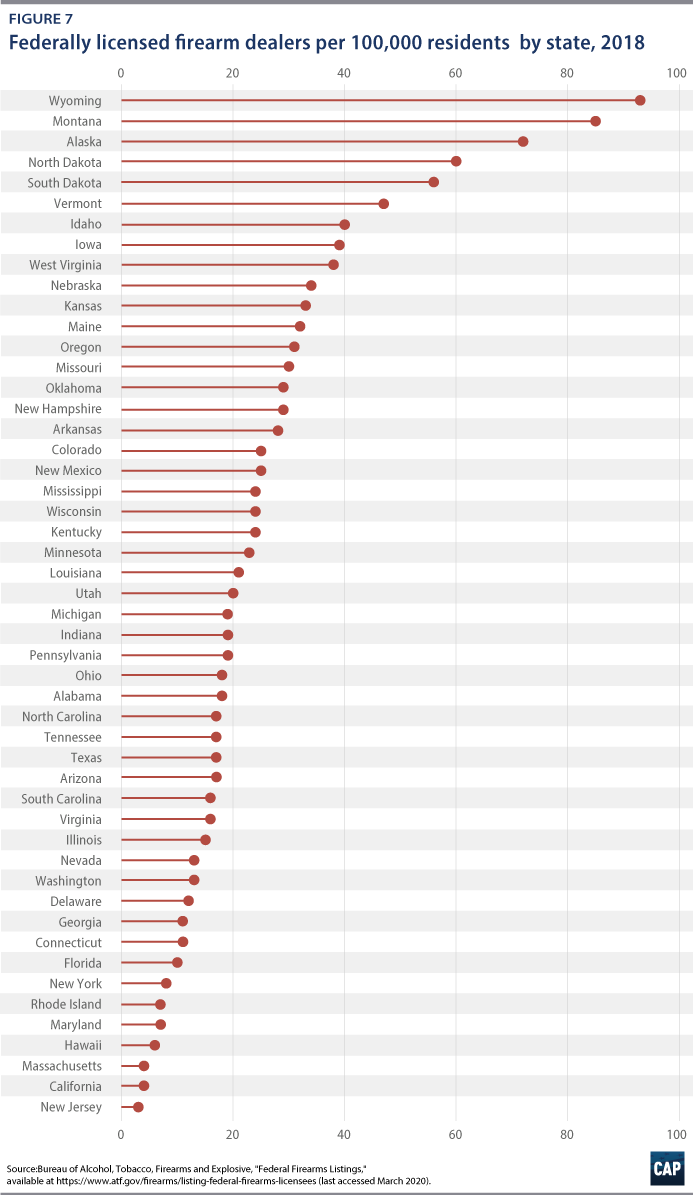

Texas, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Florida, Michigan, and California are home to the highest numbers of licensed gun dealers in terms of raw numbers, while Wyoming, Montana, Alaska, North Dakota, and South Dakota have the highest rates of gun dealers per 100,000 residents.55 (see Figure 7)

Under current federal law, individuals who are “engaged in the business of dealing in firearms”56 are required to obtain a license from ATF. The requirements to obtain such a license are minimal: The individual must be legally eligible to possess firearms under federal law, submit to a background check, provide fingerprints, and pay a $200 fee in exchange for a license to operate for three years.57 ATF investigators then conduct a qualification interview and inspection with the prospective dealer.58 However, the current law and corresponding regulation offer only vague guidance as to what exactly it means to be “engaged in the business.” Unscrupulous individuals can exploit this ambiguity in the current regulatory framework to sell guns at a high volume without becoming licensed—and without oversight from ATF or conducting background checks.59 In 2016, as part of a package of executive actions to address gun violence rolled out by the Obama administration, ATF offered updated guidance for gun sellers regarding who is required to obtain a license due to the volume and character of their business: “As a general rule, you will need a license if you repetitively buy and sell firearms with the principal motive of making a profit. In contrast, if you only make occasional sales of firearms from your personal collection, you do not need to be licensed.”60

The number of gun dealers doesn’t necessarily make clear the scope of the retail market in guns in the United States because dealers are not required to report to ATF about the volume of their sales. Indeed, ATF is prohibited under current federal law from maintaining any type of comprehensive list of gun sales that would provide insight into the true breadth and scale of this industry. One of the proxy measures available to assess the number of gun sales in the country is the number of background checks conducted using the National Instant Criminal Background Check System. Background checks have increased significantly in recent years, suggesting a rise in gun sales. While, on average, 7.7 million background checks for gun sales were conducted per year from 1999 to 2008, this number rose to 13 million from 2009 to 2018.61 Again, however, these numbers likely fail to paint the full picture, as they do not capture every gun sale through a dealer or any sales facilitated by unlicensed sellers.

Gaps in gun industry oversight

The current approach to regulatory oversight of nearly every aspect of the gun industry is deeply flawed. Through a combination of restrictive laws, legislative limitations on ATF’s ability to conduct regulatory activities, and insufficient federal resources devoted to this work, the gun industry in this country is effectively unregulated.

ATF resource limitations

The authority and obligation to enforce federal laws and regulations pertaining to the gun industry is vested in ATF. It is charged with enforcing federal criminal laws related to firearms, and ATF special agents work with their counterparts in other federal law enforcement agencies including the FBI, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), as well as state and local law enforcement agencies. They identify, investigate, and refer for prosecution individuals and groups who violate federal gun laws by illegally possessing firearms, committing violent gun crimes, and illegally trafficking firearms both domestically and internationally.

However, ATF is also a regulatory agency responsible for conducting oversight of the gun industry and ensuring that all licensed manufacturers, importers, and dealers comply with federal law. This is perhaps ATF’s most crucial role, as it is the only federal agency with this unique jurisdiction. In this role, ATF issues licenses to new businesses and conducts inspections to ensure compliance with all applicable laws and regulations and to identify potential illegal gun trafficking activity.

Despite the importance of this part of its mission, ATF has struggled for decades with serious budget limitations that disproportionately affect the agency’s regulatory work. In 2019, ATF devoted 77 percent of its $1.3 billion budget to law enforcement activities, leaving only $299 million to support the personnel and services focused on providing regulatory oversight of the nation’s gun manufacturers, importers, and dealers.62 The result: In 2019, ATF employed only 770 industry operations investigators (IOIs) in the field divisions—the professional staff who conduct compliance inspections of Federal Firearms Licensees—to oversee the more than 53,000 retail gun dealers and 13,000 licensed manufacturers that were in business that year.63 These same personnel were also responsible for inspecting the more than 9,500 licensed explosives manufacturers and dealers in business that year.64

This personnel shortage has serious consequences for efforts to ensure robust oversight of this industry. Under federal law, ATF is permitted to conduct one regulatory compliance inspection of each licensee per year, and ATF has set an internal goal of inspecting all gun dealers once every three years.65 However, current resource limitations have left the agency falling far short of either goal. In 2019, ATF investigators conducted only 13,079 compliance inspections of firearms licensees, meaning that 83 percent of those licensed by ATF to manufacture or distribute guns did not receive an inspection that year.66 These inspections are crucially important: In fiscal year 2019, 47 percent of the licensees inspected were found to have violations, and the violations that were discovered ranged from failure to properly complete the paperwork necessary for crime gun tracing to failure to conduct a background check.67 Because of the limited resources available for gun dealer compliance inspections, ATF generally prioritizes inspections of those dealers who are at risk for compliance issues, such as those who have had crime guns traced to them; have experienced theft; or are located near the southern border, where international gun trafficking often occurs, or in communities that have high violent crime rates.68

This stands in stark contrast to the approach taken to conduct regulatory oversight of the explosives industry, another part of ATF’s mission. While federal law allows no more than one permissive compliance inspection of federally licensed firearms dealers each year, it mandates that ATF conduct this type of inspection for each federally licensed explosives dealer once every three years.69 The same pool of IOIs are responsible for conducting these inspections, which means they are required to prioritize them in order to comply with the law. As a result of more frequent inspections, federal explosives licensees have far fewer violations than firearms licensees. In 2019, ATF found that 80 percent of explosives licensees had no violations during their annual compliance inspection.70 More importantly, though, explosives licensees are required to make available for ATF inspection relevant records and inventory “at all reasonable times,” resulting in ATF authority to inspect as many times a year as may be required to ensure public safety.71 By contrast, ATF needs a warrant or other specifically enumerated reason to inspect a firearms licensee outside the once-per-year compliance inspection.72

Compliance inspections are also a crucial tool for uncovering missing and stolen guns. ATF has become increasingly concerned with gun thefts from dealers, noting that burglaries of licensed gun dealers increased 48 percent from 2012 to 2016 and robberies increased 175 percent during the same period.73 In 2019, 5,603 guns were reported stolen from gun dealers nationwide.74 In addition to these thefts, a disturbing number of guns are also reported as lost or missing from the inventory of gun dealers, likely due to missing or incomplete paperwork about these sales.75 In 2019, gun dealers across the country lost an additional 7,212 guns.76 While dealers are required by law to promptly report thefts and losses to ATF, compliance inspections are a crucial tool in helping identify missing guns. In 2018, there were 1,163,980 guns initially determined to be missing from the inventory of gun dealers as a result of ATF compliance inspections. Following the inspection process, the vast majority of these guns were ultimately accounted for; however, 15,461 guns remained missing after the inspections were completed.77 These numbers also stand in stark contrast to the explosives industry, which is required by law to conduct annual inventory reconciliations78—perhaps another reason there are far fewer violations for explosives licensees and certainly fewer missing explosives.79

Legal restrictions on ATF activities

In addition to significant resource limitations, ATF’s hands are tied by a constellation of restrictive laws and policy riders attached to the agency’s budget that severely limit its ability to conduct effective oversight of the gun industry. The federal code includes a number of restrictive provisions that limit the effectiveness of ATF’s oversight authority. For example, a federal law enacted in 1986 as part of FOPA explicitly prohibits the creation of a centralized federal database containing records of “firearms, firearms owners, or firearms transactions or dispositions.”80 The responsibility for keeping accurate records related to gun sales is therefore delegated to gun dealers, who are required by law to complete paperwork for each sale and maintain accurate records of these transactions.81 Timely access to accurate records related to gun sales becomes crucial when a gun is used in the commission of a crime and local law enforcement authorities need to trace it to determine the identity of the suspected perpetrator. Because federal authorities are prohibited by law from maintaining a database of gun sales, when a gun is recovered in connection with a crime and needs to be traced, ATF personnel must first contact the manufacturer to determine which wholesaler or dealer had the gun as part of its inventory, then contact those businesses to learn the identity of the first retail purchaser.82 This can be a time-consuming process: A routine trace can take a week, although an urgent trace is usually completed in 24 hours.83 Additionally, because the transaction records are not allowed to be centralized, a gun trace will only lead to the identity of the first retail purchaser of a gun. If the gun was subsequently sold in a secondary transaction through another licensed gun dealer, that information will only be uncovered through more detailed and time-consuming investigative efforts. If it was subsequently sold in a private transaction in a state that does not require background checks for private sales, there will be no record of that sale at all.

Another weakness in the federal law limiting ATF’s effectiveness in its oversight role is the lack of any statutory or regulatory authority to require gun dealers to take specific measures to minimize the risk of theft. Nothing in the federal law or ATF regulations imposes an affirmative obligation on gun dealers to implement practices to prevent theft, such as storing guns in secure safes or using other locking mechanisms during nonbusiness hours, improving physical security of the premises, or installing a security system. Indeed, the law does not even give ATF the authority to require that gun dealers lock their doors.84 ATF provides suggested guidance to gun dealers about best practices for securing their inventory and preventing theft—such as installing an alarm system, video surveillance, and door or window bars—but this guidance lacks the force of law.85 John Ham, senior investigator and public information officer for ATF Kansas City, Missouri, explained the limitations of the law in an interview with The Kansas City Star: “We as an agency don’t have the regulatory authority to come in and say you have to have an alarm system, bars on the windows, cameras. … And while the vast majority of the industry has gone that direction themselves, it still hampers our ability to combat this as effectively as we’d like.”86

Current federal law offers only limited options for ATF to take effective action against dealers who fail to comply with applicable laws and regulations or maintain control over their potentially dangerous inventory. ATF may revoke a federal firearms license if a dealer, importer, or manufacturer has “willfully violated” any provision in federal law related to the operation of their business, if they fail to have a gun lock available at the point of sale as required by law, or if they “willfully transfer” armor piercing ammunition.87 ATF may suspend a license for up to six months or issue up to a $5,000 fine if a licensee “knowingly transfers a firearm” without conducting a background check88 and may suspend the license or issue up to a $2,500 fine for selling a gun without offering a safe storage device.89 Willfulness is not defined by statute or regulation, but ATF has provided guidance explaining that the term “is defined by case law to mean the intentional disregard of a known legal duty or plain indifference to a licensee’s legal obligations.”90

That is the full slate of options for ATF to address noncompliance with laws and regulations by licensed gun dealers unless it seeks recourse in the criminal justice system.91 There is no administrative remedy in current federal law or regulation to penalize violations by dealers that jeopardize public safety but that result from negligence or recklessness. In the absence of legal authority to take meaningful action to address this type of violation by licensed gun dealers, ATF has created a relatively toothless approach: “If violations are discovered during the course of an FFL [Federal Firearms Licensee] inspection, the tools that ATF has available to guide the FFL into correction of such violations and to ensure future compliance include issuing a Report of Violations, sending a warning letter, and holding a warning conference with the industry member.”92

As a matter of practice, ATF is failing to make effective use of these meager tools. Even when a gun dealer’s conduct does rise to the level of willfully violating the law, ATF has adopted a regulatory approach that leans away from taking strong action to revoke a license. An ATF fact sheet explains “that ATF does not revoke for every violation it finds; and that revocation actions are seldom initiated until after an FFL has been educated on the requirements of the laws and regulations and given an opportunity to voluntarily comply with them but has failed to do so.”93 A 2018 investigation by The New York Times prompted by a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit filed by Brady: United Against Gun Violence found that senior leadership at ATF “regularly overrule their own inspectors, allowing gun dealers who fail inspections to keep their licenses even after they were previously warned to follow the rules.”94 Former ATF officials described numerous examples of agency leadership overruling recommendations by IOIs to revoke licenses held by dealers who repeatedly and willfully violated the law, including a gun dealer in Kentucky who repeatedly failed to conduct background checks and a dealer in Ohio who repeatedly sold guns to prohibited purchasers.95 These former officials explained that ATF leadership was very concerned about having revocation decisions challenged in court and the potential political consequences of such lawsuits, with one interviewee explaining, “We used to kind of bend over backwards” to keep gun dealer businesses open.96 As a result, revocation numbers are low. In 2019, out of the 2,594 violations found during compliance inspections, ATF recommended revoking a license in only 43.97

By contrast, ATF has far greater authority over the explosives industry. For example, ATF may shut down a federal explosives licensee without having to meet the high standard of willful noncompliance under the agency’s broad “public interest” authority.98 Other administrative agencies that regulate similarly dangerous commodities also hold greater powers to penalize noncompliant industry members. For instance, the DEA has far-reaching authority to suspend or revoke a registrant authorized to distribute narcotics for maintenance or detoxification treatment.99 The DEA more generally may suspend pharmacy registrations in cases of “imminent danger to the public health or safety,” which is broadly defined to include a failure to “maintain effective controls against diversion” or otherwise comply with registration requirements, and in cases where due to such failure, “there is a substantial likelihood of an immediate threat [of] death, serious bodily harm, or abuse of a controlled substance.”100 This latter threat of “abuse of a controlled substance” appears to give the DEA significant discretion in shutting down noncompliant pharmacies, and the agency has utilized this critical authority to close down pharmacies in response to the opioid crisis.101 Unfortunately, ATF wields no similarly far-reaching power to administratively shut down noncompliant firearms licensees where there may be a substantial likelihood of threat to public safety.

The DEA also enjoys additional legal advantages when it suspends a pharmacy’s registration, as the suspension may continue in effect until the conclusion of both the administrative proceedings and judicial review, unless the DEA elects to withdraw the suspension sooner.102 ATF, by contrast—even when it does initiate the rare revocation action—generally is required to allow FFLs to continue operating during both administrative actions and judicial review; the law provides that ATF “shall upon request of the holder of the license stay the effective date of revocation,” meaning that ATF has virtually no discretion to immediately shut down an FFL’s operations pending administrative review.

Restrictive budget riders

In addition to restrictive language in the U.S. Code, there are numerous limitations imposed on ATF’s activities via riders attached to the agency’s budget. Beginning in 1979, Congress has inserted more than a dozen restrictive policy directives into ATF’s annual budget that prevent the agency from spending any federal funds on certain discrete activities.103 The first such rider prevented the agency from creating a centralized database of gun transactions—the restriction that was later enshrined in the federal code through the enactment of FOPA. Another rider that was first imposed in 1996 further exacerbates ATF’s challenges in performing timely crime gun traces by preventing ATF from consolidating into a searchable database transaction records from gun dealers that have gone out of business.104 ATF therefore keeps physical copies of these out-of-business records in a warehouse in West Virginia, where they are often converted into microfilm.105 Hundreds of thousands of paper records reside in bankers boxes stored in temporary cargo containers because the volume has exceeded storage space inside the National Tracing Center building. These records are subject to the elements since many of the containers leak, damaging some out-of-business records beyond legibility.106

Some of the riders are specifically aimed at restricting ATF’s ability to fully enforce federal laws related to gun dealers. One rider bans ATF from requiring gun dealers to conduct an annual inventory reconciliation to ensure that guns have not been lost or stolen.107 Another prevents ATF from denying or refusing to renew a gun dealer’s license due to lack of substantial business activity. This contributes to a glut of dealers, which makes it more difficult for ATF to effectively allocate its scarce regulatory resources. In addition, a rider first imposed in 1994 dictates that ATF may not “transfer the functions, missions, or activities of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives to other agencies or Departments,” meaning that the agency cannot address its significant resource gaps by seeking assistance to perform activities such as gun dealer inspections from better-resourced federal agencies such as the FBI or the DEA, which has similar experience regulating the pharmaceutical industry.108

Another set of riders was first attached to ATF’s budget in 2004 that, among other things, drastically limited the ability of ATF and other law enforcement agencies to use and disseminate trace data—data that links guns found at crime scenes to a manufacturer, the dealer that originally sold it, and possibly the identity of the owner. While the worst of these riders were later amended to minimize the impact on law enforcement investigations, a restriction remains that prevents the public dissemination of trace data other than in an aggregated annual report.109 This means that researchers are unable to put their substantial expertise to use identifying complicated interstate and international gun trafficking patterns and policymakers are unable to develop data-informed laws and policies to identify and prevent common gun trafficking methods.

Other riders undermine ATF’s ability to regulate certain categories of firearms that receive special treatment under the law: curios and relics. Under current federal regulations, curios and relics are defined as firearms “which are of special interest to collectors by reason of some quality other than is associated with firearms intended for sporting use or as offensive or defensive weapons.”110 Any firearm that was manufactured at least 50 years ago qualifies as a curio or relic, as well as others of museum interest or that are otherwise rare or novel.111

Curio and relic firearms occupy a unique place in the federal firearms licensing scheme. Individuals can obtain a collector’s license from ATF that allows them to buy and sell curio and relic firearms much more freely than is usually permitted under federal law—including without a required background check—and that allows these licensees to transfer guns across state lines to each other, something that unlicensed individuals are prohibited from doing.112 ATF maintains a list of all firearms that meet this classification; however, a rider first imposed in 1996 prevents ATF from changing the definition of curio or relic in the regulations or taking any firearms off the approved list as it existed in 1994.113 Constraining ATF’s ability to evaluate the guns receiving curio or relic classification and requiring that the current definition remains unchanged means that there are dangerous, serviceable weapons in U.S. communities, including semiautomatic military surplus rifles manufactured only 50 years ago, which are subject to far less stringent regulations than comparable modern weapons. These are not merely antique guns that are locked away in display cases—modern Vietnam War-era military semiautomatic rifles still in military service, such as the SKS and Dragunov SVD, currently qualify as curios and relics.114 A related rider prevents ATF from denying an application for permission to import a firearm that is a curio or relic.115

Heightened regulation of certain types of firearms and accessories

Current federal law does not treat all types of firearms equally. For nearly 90 years, certain types of firearms and accessories have been deemed especially dangerous to public safety and are therefore subject to additional restrictions on their sale and possession. In 1934, in response to a deadly spike in organized crime, including marked increases in violence against police officers during Prohibition,116 the National Firearms Act was enacted. This law imposed heightened regulation over machine guns, short-barreled shotguns and rifles, and silencers (also known as suppressors), primarily by imposing a $200 tax on the manufacture or transfer of these guns, as well as requiring individuals to register these guns with the federal government.117 The NFA has been amended a few times in the years since its enactment, although the $200 tax has never been increased.118 Had the tax kept pace with inflation, it would have risen to around $3,900 in 2020.119 The most significant change to the law occurred with the enactment of the Firearm Owners’ Protection Act in 1986, which prohibited the possession or transfer of all machine guns entirely, except for those that were legally possessed prior to 1986.120

Under the current iteration of the NFA, the following restrictions apply to NFA weapons and accessories:

- Machine guns: The possession, purchase, or transfer of a machine gun is prohibited except for those machine guns being used by government agencies or that were lawfully possessed before May 19, 1986, when FOPA became law.121 Machine guns possessed by civilians before 1986 are required to be registered with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives;122 lawfully registered possessors of machine guns are permitted to transfer machine guns to other lawfully registered possessors, provided they document the transfer with ATF and the recipient pays the $200 transfer tax.123

- Short-barreled shotguns and rifles: Manufacturers, importers, or dealers of these firearms need to obtain a specialized license from ATF.124 Individuals seeking to purchase one of these firearms must complete an application and pay a $200 transfer tax.125 The transfer of these firearms to civilians requires notification to ATF, including registration of the firearm under the name of the recipient.126

- Silencers: Manufacturers, importers, or dealers of silencers or devices built from parts intended to fabricate silencers need to obtain a license from ATF to engage in the business of producing or selling silencers, including paying a $200 occupational tax.127 Individuals seeking to purchase a silencer must complete an application and pay a $200 transfer tax.128

One of ATF’s core regulatory responsibilities is to enforce the NFA. ATF’s National Firearms Act Division is tasked with managing the National Firearms Registration and Transfer Record (NFRTR).129 The NFA Division also processes all applications related to NFA firearms and silencers and updates the centralized NFRTR to account for changes in NFA-registered firearms, including noting when they are lost or stolen; modifications to the firearms; and the transfer, destruction, or export of these firearms. Additionally, the NFA Division maintains a record of Federal Firearms Licensees who import, manufacture, or sell NFA firearms. The division also serves as a resource for technical guidance to ATF offices throughout the nation.

The NFA was enacted in 1934 by Congress to address the existential threat of unrestricted commerce in military-grade firearms that was fueling vicious gang wars. The $200 making-and-transfer tax levied on such firearms was prohibitive in 1934, Congress’ intent being to stringently regulate sales of machine guns, short-barreled shotguns and rifles, and silencers, among other weapons commonly used by members of criminal organizations.130 It should be noted that by 1930 law enforcement line-of-duty-deaths due to gunfire had climbed to well more than 300 that year and held steady until passage of the NFA, after which officer gunfire deaths dropped precipitously.131 Fast forward to 2020, fewer than 10 crimes have been committed using firearms registered on the NFA; Congress’ intent continues to be realized as strict regulation of the most dangerous weapons keeps them out of criminal hands.132

A looming public safety crisis: Short-barreled long guns

One of the most significant functions ATF serves is to determine which firearms, destructive devices, and accessories fall into the classifications of weapons that require heightened regulation under the NFA, including registration in the NFRTR or prohibition of sale in a consumer market. ATF’s Firearms Technology Industry Services Branch (FTISB) serves as the technical authority to determine how firearms should be classified under federal law.133 When a manufacturer of firearms and firearm accessories creates a new product that it wants to sell in the consumer market, it sends a sample to the FTISB to determine whether the firearm or the accessory would qualify as an NFA weapon and therefore be subject to heightened regulation.134 The FTISB examines and tests the sample, then issues a letter to the manufacturer with its determination of whether the firearm or accessory falls into an NFA category. The intent behind this regulatory process is to ensure firearms and firearm accessories that require additional regulation, as determined by federal law, are registered and taxed accordingly.135

How bump stocks went from legal to illegal accessories

A recent example demonstrates the importance of this ATF regulatory function to protect public safety. In 2010, ATF received an application for review of a replacement stock, referred to by the manufacturer as a “bump stock,” which would be added to an AR-15 style rifle, purportedly to help people with limited hand mobility fire a rifle.136 In effect, this accessory replicated the firing action of a fully automatic machine gun by harnessing the recoil of a semiautomatic firearm to continuously fire multiple bullets with a single trigger pull.137 ATF’s initial review of the bump stock found that it did not qualify as a firearm under the NFA—meaning that it did not meet the statutory definition of a machine gun—and therefore could be sold as a firearm accessory without any additional restrictions or oversight.138 On October 1, 2017, a shooter, armed with firearms, ammunition, and bump stocks, opened fire on a music festival in Las Vegas, killing 58 people and injuring hundreds more.139 Law enforcement on the scene and video footage of the attack showed that the use of bump stocks on multiple rifles enabled the shooter to mimic automatic fire during the rampage, firing more than 1,000 rounds of ammunition in just a few minutes.140 Outrage over the shooting, coupled with widespread calls for banning bump stocks, with even the National Rifle Association publicly supporting restrictions on bump stocks,141 resulted in ATF reassessing its original determination on the devices and commencing a formal rulemaking process to reclassify bump stocks as machine guns. After receiving tens of thousands of comments supporting the proposed rule, in December 2018, ATF issued a final rule defining bump stocks as “firearms” under the NFA and therefore requiring heightened regulation under that law.142

One common determination ATF is asked to make relates to whether a new firearm design qualifies as a short-barreled shotgun or rifle, which are more stringently regulated under the NFA than regular shotguns and rifles. The impetus for enhanced regulation and restrictions of short-barreled long guns is tied both to the ease with which these weapons are concealable and to the extent of damage these weapons are capable of inflicting when used to perpetrate a crime, given that they fire large-caliber ammunition capable of piercing the soft-body armor commonly worn by law enforcement officers.143 Under federal law, both shotguns and rifles are, by definition, designed to be fired from the shoulder using two hands and are not easily concealable; they are subject to minimum barrel length and overall length requirements.144 Congressional support for the original legislation passed in 1934 specifically referred to the extensive use of short-barreled shotguns and rifles by members of organized crime groups, including the weapons used to commit the 1929 St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago.145

Despite the vital importance of ensuring that these dangerous weapons are not freely available in U.S. communities, recent user-based classification decisions by the FTISB raise serious concerns about how ATF is approaching this responsibility. An excellent example of the FTISB’s failure to dutifully enforce the NFA is the line of Mossberg short-barreled shotguns. On March 2, 2017, the FTISB issued a letter to Mossberg regarding its new 12-gauge pump action firearm, model 590 “Shockwave.” The letter specifically notes that the sample submitted by Mossberg has a 12-gauge, smooth-bore barrel that is approximately 14 and seven-sixteenths inches long, with a total length of 26-and-a-half inches.146 The FTISB determined that this firearm did not qualify as a short-barreled shotgun under the NFA because it has a shotgun-style receiver but did not have a shoulder stock and instead had a “bird’s head grip.”147 As a result, this gun can be purchased and possessed without any of the additional restrictions imposed by the NFA on short-barreled shotguns. However, the FTISB’s determination came with a vital caveat. The FTISB letter stated, “Please note that if the subject firearm is concealed on a person, the classification with regard to the NFA may change.”148

This caveat from the FTISB is deeply problematic, as it essentially notes that the NFA classification of the firearm is dependent on the actual use of the firearm in each specific instance, rather than the fact that the firearm’s dimensions make it concealable and thus a short-barreled shotgun as defined by current ATF regulations. The FTISB’s letter to Mossberg implies that as long as users do not conceal this firearm, it does not require registration as an NFA firearm. That is patently at odds with the intent of the FTISB’s role, which is to determine whether firearms based on their design and dimensions could, in any circumstances, be classified as NFA firearms. The determination should not be reliant on the use of the firearm in specific circumstances but on the technical specifications of the firearm itself, regardless of any particular user’s intent. Some in the gun enthusiast community responded with both surprise and delight at this apparent new workaround to the NFA.149

Mossberg has continued to exploit this NFA loophole, creating more Shockwave models that are essentially short-barreled shotguns without the NFA registration or tax requirements. The most recent editions of the Shockwave were released before the 2018 holidays and were highlighted in a The Firearm Blog post titled, “Fudge the NFA! NEW Mossberg 12 Gauge Shockwaves for 2019,” that includes a review of the models that explicitly noted they all “are built on the 590 design, feature a 26.37’’ overall length, and have a bird’s head grip allowing them their special non-NFA classification.”150 Mossberg’s non-NFA short-barreled shotgun design has caught the attention of other gun manufacturers. Recently, Remington released the V3 TAC-13, a semiautomatic 12-gauge shotgun. Like the Shockwave, the V3 TAC-13 does not use a buttstock, equipped instead with a bird’s head grip in a design that one reviewer dubbed “the tax stamp trick.”151

The gun industry has also found another NFA dodge to create the functional equivalent of a short-barreled rifle that is not subject to heightened regulation or transfer tax: the pistol brace. Pistol braces are common firearms accessories first produced in 2013 by manufacturers claiming the intent was to help wounded and disabled veterans shoot AR-style pistols easier and more safely, by enabling a user to only rely on one hand to control and stabilize the firearm when using the brace, rather than needing to use both hands.152 In 2011, the company Shockwave Technologies submitted a new model of pistol brace to the FTISB for a determination of whether it would require registration under the NFA. ATF reviewed the Shockwave Blade AR pistol brace and determined that the brace would not turn a firearm into an NFA-classified firearm when used as a forearm brace and was therefore not subject to the requirements of the NFA. However, the letter of determination also included a crucial caveat, noting the brace “is not a ‘firearm’ as defined by the NFA provided the Blade AR Pistol Stabilizer is used as originally designed and NOT used as a shoulder stock. ”153 (emphasis in source) Again, ATF grounded its determination in the specific use of the accessory in each individual instance, rather than the potential uses based on its design, given that the brace can be used to “convert a complete weapon into … an NFA firearm.”154 The FTISB’s decision was so unorthodox that it seemed to take gun enthusiasts by surprise, with The Truth About Guns blog posting an article on the decision stating, “The astute among you will notice that this device looks strikingly similar to a stock,” as well as linking to the determination letter with the words, “The reply was a bit surprising.”155

This decision led to a proliferation of pistol braces that received similar decision letters from ATF, indicating that the industry seized on the opportunity to innovate around the NFA using the reasoning provided by ATF in the Shockwave letter.156 However, the FTISB’s decisions on stabilizing braces were so unusual that the agency began to receive multiple inquiries from gun owners seeking clarification.157 On January 16, 2015, ATF issued an open letter specifically on the “proper use of devices recently marketed as ‘stabilizing braces’.”158 In the letter, ATF advised that the agency’s determination that these devices are not subject to the NFA “is based upon the use of the device as designed” and that if a pistol brace “is redesigned for use as a shoulder stock on a handgun with a rifled barrel under 16 inches in length,” the resulting firearm does constitute an NFA weapon.159 The open letter advised that “any person who intends to use a handgun stabilizing brace as a shoulder stock on a pistol (having a rifled barrel under 16 inches in length or a smooth bore firearm with a barrel under 18 inches in length) must first file an ATF Form 1 and pay the applicable tax because the resulting firearm will be subject to all provisions of the NFA.”160

The open letter appears to have caused confusion among people who were purchasing pistol braces, with many questioning whether the use of a brace required formal licensing under the NFA.161 SB Tactical, the creator of the original pistol brace, challenged the open letter’s claims that using the brace and firing from the shoulder would create an NFA-classified firearm, resulting in a response from the FTISB, which reiterated that the agency deemed these braces to be legal provided they are used as forearm braces and not used as a shoulder stock.162 The clarification letter went further, stating, “ATF has concluded that attaching the brace to a handgun as a forearm brace does not ‘make’ a short-barreled rifle because in the configuration as submitted to and approved by FATD [ATF’s Firearms and Ammunition Technology Division in which the FTISB sits], it is not intended to be and cannot comfortably be fired from the shoulder.”163 Additionally, according to the letter, if a user of a firearm equipped with a stabilizing brace does fire the weapon from the shoulder, it still doesn’t constitute creating an NFA firearm unless the user explicitly “redesigned the firearm for purposes of the NFA.”164 Therefore, ATF’s official determination on pistol braces is that AR-15 pistols can in fact be equipped with a brace and fired from the shoulder without creating an NFA-classified short-barrel rifle unless the brace is deliberately redesigned to become a stock, a clarification that was relished by gun forums, with The Truth About Guns writing a post detailing the decision with the title “YES, It is Legal to Shoulder an AR-15 Pistol Equipped with an Arm Brace.”165

ATF issued another notice on December 11, 2018, declaring that the FTISB will only review requests for determination of accessories under the NFA or Gun Control Act if the submission includes a firearm with the accessory attached as the user intended.166 This approach essentially delegates the authority to determine whether a firearm or accessory qualifies under the NFA to the industry itself, which has a profit-driven motive to ensure that it does not. By asking manufacturers to send accessories already attached to firearms as they are purportedly intended to be used, ATF is abdicating itself of the responsibility to conduct thorough inspections to determine whether an accessory as designed could be used to turn a firearm into an NFA-categorized firearm. This approach involves an inappropriate level of deference to the manufacturers of these weapons and accessories that allows the marketing of a product to determine its classification under federal law.

Underground gun-makers

In addition to grave problems surrounding the lack of regulation of corporate manufacturing of firearms, ammunition, and firearm accessories, there exists an entire segment of the firearms industry that operates with even less oversight than traditional manufacturers: homemade firearms, ammunition, and firearm accessories makers. There is a robust online community of amateur gun-makers offering tips and tricks for making guns at home and selling kits to allow people to do so that often come very close to the line of what is legally permissible.167 There are two primary concerns related to homemade firearms and accessories: First, these guns and accessories are often made using parts that can be purchased without a background check, creating an easy avenue for individuals prohibited from gun possession to evade that law and make guns at home. Second, homemade guns and accessories are often made with parts that are not required to include a serial number, rendering the finished firearm untraceable if it is later used in a crime.

Ghost guns

Under current federal law, gun manufacturers and importers are required to engrave a serial number on the frame or receiver of each firearm168 and gun dealers are required to conduct a background check before selling any firearm.169 The law defines “firearm” for purpose of these requirements in relevant part to mean “any weapon (including a starter gun) which will or is designed to or may readily be converted to expel a projectile by the action of an explosive” or “the frame or receiver of any such weapon.”170 A firearm’s frame or receiver are the structural components of a firearm that hold the key parts that enable it to actually shoot, defined by regulation as “that part of a firearm which provides housing for the hammer, bolt or breechblock, and firing mechanism.”171 ATF has long interpreted this definition of firearm to include only fully finished firearms, frames, and receivers, meaning that those that are not technically finished and require a few additional steps before they can be used to make a fully functional gun are not subject to these legal requirements. Often referred to as “unfinished receivers” or “80 percent receivers,” these receivers generally only require a person to follow any of the myriad tutorial videos or guides online and use basic tools to complete the receiver by drilling a few holes for the selector, trigger, or hammer pins.172 Guns made at home using these unfinished receivers have become known as “ghost guns” because they are untraceable when they are recovered after use in a crime.173 A former ATF special agent described the ease with which fully functional guns can be made at home using these parts: “If you can put Ikea furniture together, you can make one of these.”174

A robust segment of the gun industry has developed in recent years focused on manufacturing, marketing, and selling unfinished receivers. There is a vast array of online merchants selling kits for 80 percent receivers.175 One website is called Ghost Guns, specializing in helping consumers “legally manufacture unserialized rifles and pistols in the comfort and privacy of home”176; another is called 80 Percent Arms.177 There is also a proliferation of information around how to build a gun using a gun kit with an unfinished receiver, much of which explicitly advertises how to make untraceable firearms without a background check at home.178 For example, 80% Lowers is an online site with content dedicated to helping people build untraceable, unregistered firearms at home.179 Gun University has a page dedicated to showing people how to build a Glock at home without a serial number or registration.180 In 2013, Mother Jones reported on “build parties” that are hosted by expert gun assemblers to aid people building firearms without any background check, relying instead on people responding truthfully to a list of questions related to lawful firearm possession.181 Unfinished receivers have also added a new layer of difficulty to reducing international gun trafficking. For example, a 2016 report indicates that Mexican criminal organizations take advantage of trafficking in firearm parts to acquire guns, further complicating any efforts from security agencies on both sides of the border.182

The dangers associated with ghost guns are not theoretical. In 2013, a shooter opened fire in Santa Monica, California, shooting 100 rounds, killing five people and injuring several others at a community college using a homemade AR-15 rifle.183 Reporting indicates the shooter had previously tried to purchase a firearm from a licensed gun dealer and failed a background check, potentially indicating why he opted to order parts to build a gun instead.184 In 2017, in Northern California, a man prohibited from possessing firearms ordered kits to build AR-15-style rifles.185 On November 13, he initiated a series of shootings that began with fatally shooting his wife at home, followed by a rampage the next day during which he fired at multiple people in several different locations, including an elementary school, killing five people and injuring dozens more.186 In 2019, a shooter used a homemade gun kit to build a .223-caliber firearm used in a bar in Dayton, Ohio, to fire 41 shots in 32 seconds, shooting 26 people and killing 9.187 These kits create an easy way for individuals who are prohibited from buying a gun and could not pass a background check, such as the Dayton shooter, to easily evade that law and build a gun at home.188

Law enforcement has grown increasingly concerned about the proliferation of ghost guns. In 2019, District of Columbia police recovered 115 ghost guns, a 360 percent increase from 2018, when they recovered 25 ghost guns, and a 3,733 percent increase from 2017, when only three such firearms were recovered.189 In California, federal law enforcement reports that 30 percent of all guns recovered from crime scenes are blank, without a serial number, and are therefore untraceable.190 The untraceable nature of these weapons makes them highly desirable for firearm traffickers and criminal organizations. In 2015, the New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman authorized the Organized Crime Task Force and the New York State Police to conduct Operation Ghostbusters, focused on identifying a ghost guns trafficking ring.191 The outcome resulted in officers discovering a ghost gun construction operation that built fully functional firearms using unfinished receivers and firearm parts and then transferred them to firearm traffickers.192 The two men responsible for the ghost gun operation received sentences of nine and 11 years, respectively, for the criminal sale of firearms in the first degree, among other charges.193 In 2018, the Los Angeles Police Department and ATF conducted an operation that found criminal organizations were relying on building arsenals using homemade firearm kits.194 In addition, a new spike in online purchasing of ghost gun kits was reported when much of the country was staying at home during the onset of the coronavirus crisis as part of a larger surge in gun buying during this period.195

Advancements in 3D printing technology have created another option for people seeking to make untraceable guns from home. While 3D printing an entire firearm has been successfully completed and is cause for some concern,196 the more pressing concern is the capability of using 3D printers to create certain firearm components at home. For example, the lower receiver of an AR-15 in particular is essentially the part that makes a gun functional: It houses the fire control and trigger groups, the bolt catch, and the magazine release.197 The ability to 3D print lower receivers means that individuals can produce or buy untraceable integral pieces of firearms from private sellers.198 Recently, AR-15 upper receivers that house, among other things, the barrel and the bolt carrier group, have begun to be successfully 3D printed and used to fire hundreds of rounds.199

To date, only two states, California and New Jersey, have enacted comprehensive laws to address the problem of homemade, untraceable firearms.200 In additional, federal law requires that guns contain a sufficient amount of metal to make them apparent when they are brought through metal detectors; however, 3D printed firearm components allow individuals an easy way to evade this law. There is currently no federal oversight on the production of 3D printed firearms or sufficient reporting requirements to ensure that these guns are produced with the necessary metal materials to follow federal regulations.201

Homemade ammunition

Homemade ammunition, commonly called “reloads,” presents a different set of concerns. Ammunition is less regulated than firearms, without federally mandated background checks before purchase or transfer or requirements for documentation of sales of ammunition conducted by dealers.202 Adding to the unknowns within the commercial ammunition market is the fact that there is currently no way to assess the scale or prevalence of homemade or reloaded ammunition. The lack of oversight or any real ability to monitor the production of homemade ammunition makes it difficult to determine exactly what types of ammunition rounds are being produced.

Gun enthusiasts often rely on similar online resources to obtain the materials needed to make cartridges at home, with access to videos and forums similar to those focused on homemade firearms, for personal use or to sell.203 Ammunition can be produced at home with the right equipment, shell casings, bullets, igniters, and powder, all of which are readily available online or at gun stores.204,” January 21, 2020, available at https://www.pewpewtactical.com/beginners-guide-to-reloading-ammo; Cabela’s, “Reloading,” available at https://www.cabelas.com/category/Reloading/104761080.uts (last accessed May 2020).] Some people even choose to melt metal and cast their own casings or bullets without any safety regulations or agency oversight.205

There are many dangers associated with homemade ammunition, including stockpiling, improper or unsafe storage of ammunition and components, unsafe manufacturing conditions, poor quality control, and potentially defective products.206 Online forums include stories shared by people illustrating the dangers of reloaded ammunition, including sharing details of instances where reloaded ammunition resulted in damage to the firearm or injury to the user.207

Homemade silencers

Silencers are accessories designed to muffle or disguise the sound of gunfire. When used with a firearm, a silencer reduces the sound of gunfire and virtually eliminates muzzle flash, making it difficult for a shooter’s location to be determined. The danger posed by silencers was evidenced by the mass shooting in Virginia Beach on May 31, 2019. In that case, the shooter used two pistols, one equipped with a silencer, to commit a mass shooting within a municipal building that killed 12 people, wounding four others. Witness accounts note they did not recognize the sounds as gunfire, with one witness’ statement to police noting, “If it was a regular gunshot, we would’ve definitely known a lot sooner, even if we would’ve had 30 or 60 seconds more … I think we could’ve all secured ourselves … all of us could’ve barricaded ourselves in.”208

Federal law requires a license from ATF to manufacture or sell silencers, and individuals seeking to buy them must first obtain approval from ATF, a process that can take many months because of a backlog in processing these applications.209 In recent years, the gun lobby has included a push to deregulate silencers as a top priority for its federal legislative agenda, arguing that this measure is necessary to protect the hearing of recreational shooters (and their guide dogs) and titling the bill the Hearing Protection Act.210 A larger bill that included similar provisions that would reduce federal regulation of silencer sales, treating silencers the same as non-NFA firearms under federal law, was passed by the House Committee on Natural Resources in September 2017 on a party-line vote.211 The dangerous push to deregulate silencers was bolstered following the leak of a white paper drafted by Ronald Turk, former associate deputy director of ATF, suggesting that the Trump administration support efforts to deregulate silencers by taking them out of the NFA, arguing that ATF’s resources were being wasted in processing silencer applications.212 Following the October 2018 mass shooting in Las Vegas that left 58 people dead and hundreds injured, legislative efforts to deregulate silencers lost momentum.213

Individuals are permitted under current federal law to manufacture their own silencer at home, as long as they do not offer it for sale and they register it with ATF.214 This aspect of the law has created the opportunity for unscrupulous actors in the gun industry to sell firearm accessories that are not on their face silencers—such as solvent traps, barrel shrouds, or flashlight tubes—but that can be easily converted to this use with instructions found online or that have the effect of muffling the sound when used as a silencer.215 ATF has taken enforcement action against some vendors for selling products that are effectively silencers without a license;216 however, the agency’s approach to this issue has been inconsistent, with ATF often relying on the stated purpose of the accessory, rather than its potential use as a silencer.217

Regulating guns and ammunition for safety

Nearly every industry involved in manufacturing and selling consumer products is subject to regulation by the federal government to ensure that products are safe for consumer use. Safety-focused regulation of consumer products helps ensure that defects or problems with products are addressed in a timely manner through actions such as consumer alerts and product recalls. A range of federal agencies serve a consumer product safety regulatory function: Food items and prescription drugs are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and the Drug Enforcement Administration, motor vehicles are under the jurisdiction of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, and recreational goods and household products are regulated by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC).218

The CPSC was created in 1972 through the enactment of the Consumer Product Safety Act. The stated purpose of the creation of this new federal agency was to “protect the public against unreasonable risks of injuries and deaths associated with consumer products.”219 The CPSC is charged with creating and enforcing mandatory standards for consumer products, issuing bans on consumer products deemed to be unsafe for public consumption, establishing voluntary standards for manufacturers and business to adopt, and overseeing recall procedures.220 The CPSC also conducts research on potential hazards and engages with manufacturers and consumers, educating the former on regulations and safe product development and the latter on the work of the CPSC.221 The commission has jurisdiction over a vast array of consumer products, ranging from children’s toys and clothing to household appliances and chemicals to fireworks.222 However, the CPSC does not have jurisdiction over automobiles, alcohol, cosmetics, drugs, firearms, food, pesticides, medical devices, or tobacco.223 Each of these has a specific separate agency224 that serves a regulatory and safety oversight function with one notable exception: firearms and ammunition. When the bill to create the CPSC was first debated in Congress in 1972, an effort led by Rep. John Dingell (D-MI)—who was a gun rights advocate and vocal supporter of the NRA at the time—exempted firearms and ammunition from the new agency’s jurisdiction.225 In 1975, efforts to amend the CPSC’s mandate to include firearms failed.226

The lack of consumer protection oversight of firearms and ammunition has resulted in injuries and death for users, without the same legal recourse or protection available to other consumers when facing similar dangers from products under CPSC’s jurisdiction.227 Consumers of firearms and ammunition are required to operate with a “buyer beware” approach, generally having to rely on the good faith of the industry itself or online gun forums or word of mouth for information on defective firearms or ammunition.228

The damage done by defective guns

There have been a number of high-profile incidents of design defects or manufacturing flaws of firearms leading to injury or risk of injury or death. In 2017, law enforcement and consumers began raising concerns about the SIG SAUER P320 pistol firing unintentionally.229 In February 2018, a sheriff’s deputy suffered a shattered femur when her pistol fired while she was removing it from a holster.230 In January 2017, a member of Stamford, Connecticut’s, Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) team was shot in the leg when he dropped this gun.231 After these stories were publicized, the manufacturer was accused of being aware of the defective trigger mechanism: The pistol was originally produced to fill an army contract, and in testing, the gun’s design was found to be defective, with the gun sometimes firing if dropped.232 Reporting suggests that SIG SAUER addressed the problem for the weapons sold to the army but continued selling the original design of the P320 pistol to law enforcement agencies and the civilian market without any modifications to ensure the gun was safe and would not fire when dropped.233 More than 500,000 of the defective pistols were sold on the commercial market before the manufacturer offered a voluntary trigger upgrade on the pistol model to improve the functionality and reliability of the firearm; however, in offering the upgrade, the manufacturer did not directly acknowledge any defects in the product, nor did the manufacturer issue a recall of the product.234 SIG SAUER released a statement on August 8, 2017, claiming that “the P320 meets U.S. standards for safety,”235 despite the fact that firearms are excluded from having a federal agency actually issue any federal standards for product safety.